Introduction

For hundreds of millions of years, our ancestors have walked this planet. Until fairly recently, however, our lights were turned off. There was no consciousness—no agent with a sense of self—to observe this terrifying yet sublime spectacle. What existed was only the blind and mechanical Darwinian drive to survive and procreate.

Then, just a few million years ago, the lights of consciousness turned on, and man found himself—in medias res—in an unfamiliar body governed by instincts in a natural world full of danger and beauty. From that moment on, man was set the task to make sense of both the world and himself. Given the immensity of the task, progress was mostly slow and painful, yet often deeply meaningful.

Along the journey, man was often led astray. In many instances, he was enchanted by his thirst for meaning. He read into the forces of nature and into his instincts and dreams the work of gods and demons. At the same time, there was little acknowledgment—let alone concern—for the individual and no idea of a free will deserving of inalienable rights. Moreover, there was no method to discern fact from fiction, nor any concept of empirical evidence. But then, in the last few thousand years, things changed rapidly. In the East, the concept of impartial observation was relentlessly applied to the mind. In the West, it gave rise to science.

The main purpose of this book is to trace this coming into consciousness of the human race and its growing understanding and control over world and mind. This book is, therefore, not a conventional history book. It will focus not just on the succession of wars and kings, but mainly on the soul-stirring and brave individuals who, through their ideas and insights, shaped our world and our self-perception.

It is the greatest story ever told.

Amsterdam, 2025,

S.P. Dinkgreve

Part 1:

The Dawn of Man

Our lives today vastly differ from those of early humans, yet we share about the same genes, the same brain, and the same body. Despite all our modern technology, the same ancient impulses and emotions lie encoded in our unconscious. This likely explains why we are still stirred to our core when we listen to the old legends of heroes doing great deeds, why we find ourselves in awe after experiencing a symbolic dream, and why many of us still believe in heaven and hell, spirits and the soul.

In this first chapter, we will peer deep into our archaic past, to a time when man lived among the animals in the wild and was more in tune with these ancient impulses. We will first examine the fossil and archeological records to trace the early stages of human evolution. Then we will study modern tribal cultures to figure out what life must have been like in these early days. Along the journey, we will meet fierce hunters, mysterious shamans, and mythologies filled with spirits and tricksters.

The evolution of our species

Our species, Homo sapiens, evolved from a group of primates. Among these animals, the chimpanzee is our closest surviving relative. However, this does not mean that we evolved directly from chimpanzees. Instead, we share a common ancestor. Chimps split from our evolutionary timeline about seven million years ago, and we have taken our separate ways ever since. Yet despite being on distinct evolutionary tracks for so long, we still share about 99% of our DNA. Obviously, a lot of qualitative difference is hidden in that one percent.

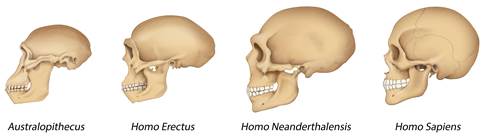

The evolution from primates to human beings is convincingly documented in our fossil record. One of the earliest transitional species was Ardipithecus, which lived about 4.4 million years ago in Africa. Studies of its skeletons suggest that this animal was bipedal, although its feet were still better suited for grasping than walking. From around 4.2 million years ago, fossils of the species Australopithecus emerged. Two members of this species even left footprints in volcanic ash, providing direct evidence of their bipedal movement (see Fig. 1). Nevertheless, their skeletons still resemble apes more than humans (see Fig. 2) and they stood not much taller than one meter.

Fig. 1 – Cast of footsteps of two Australopithici (c. 3.7 million years ago) (NegesoMuso, Laetoli Museum)

The species Homo habilis appeared around 2.8 million years ago and figured out how to use simple stone tools. They smashed stones together to produce flakes that could be used as knives (see the left side of Fig. 3). The appearance of these tools marked the start of the Paleolithic, or Old Stone Age.

Fig. 2 – Skull of an Australopithecus (3.9 million years ago) (Leroi-Jose Braga & Didier Descouens, CC BY-SA 4.0; Transvaal Museum, South Africa)

Fig. 3 – Early stone tools used by Homo Habilis (left) and Homo erectus (right) (Locutus Borg, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Fig. 4 - The evolution of the skull (Shutterstock)

The next step in our evolution was Homo erectus, who appeared around 1.8 million years ago and used more sophisticated stone tools (see the right side of Fig. 3). Homo erectus was also the first to build simple rafts and to control fire, which they used for protection, warmth, and cooking food. They also were the first to move out of Africa, perhaps as early as 1.7 million years ago.

Homo neanderthalensis diverged from our lineage about 600,000 years ago. Generally, the Neanderthals can be seen as a more robust version of us. They were stronger and better runners but were also somewhat shorter. In Fig. 4, we can see that their skulls resemble ours much more than their predecessors, and their brains have about the same size. A recent find of Neanderthal DNA in a toe bone made it possible to study our similarities and differences at a molecular level. Comparing their DNA to our own, we now also know that many modern humans, especially those outside of sub-Saharan Africa, interbred with Neanderthals.

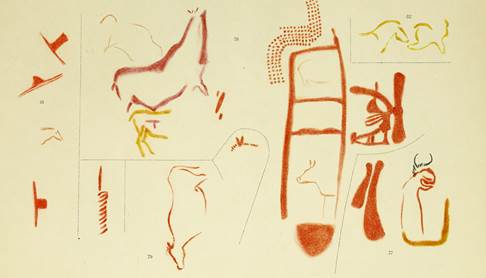

Fig. 5 – Copy of a cave painting that might have been made by a Neanderthal (La Pasiega à Puente-Viesgo, Abbe Breuil, 1913)

Fig. 6 – A mammoth skeleton (Shadowgate, CC BY 2.0; Museum of Natural History, France)

Around 40,000 years ago, the Neanderthals went extinct. A cause for this might strangely be their stronger build, which made them more inclined to engage in direct combat with wild animals, often leading to premature death. This hypothesis is supported by the numerous injuries found on their skeletons.

The Neanderthals also mirrored us closely in terms of behavior. They made composite tools, such as wooden spears with stone tips, and they pierced and painted shells to make necklaces. It appears that Neanderthals also buried their dead in caves. The evidence presented for this in the past has often been questionable, yet in at least two instances we have found complete skeletons placed in what seem to be hand-dug holes. We have also found skeletons covered in red ochre, accompanied by stone tools and animal bones. If these skeletons were also part of burials (of which we aren’t sure), these might well constitute the earliest evidence of funeral rituals.

Recently, it was proposed that several cave paintings in Spain, including the outlines of hands and drawings of animals, might have been created by Neanderthals (see Fig. 5). These paintings are dated to a stunning 64,000 years ago, ten thousand years before the first evidence of Homo sapiens in Europe.

Homo sapiens

|

Our species, Homo sapiens, evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago. They left the continent probably about 70,000 years ago, reached Europe around 40,000 BC, Australia around 50,000 BC, and the Americas at least by 15,000 BC, though possibly earlier. Over the vast timespan of our existence, the earth passed through two glacial periods, with the last one ending around 11,700 years ago. The last glaciation peaked around 26,500 years ago, when large parts of Europe, North America, and Asia were covered by massive ice sheets, in some places several kilometers thick. With so much of the Earth’s water locked in ice, sea levels were a stunning 125 meters lower than they are today, exposing enormous swathes of land that are now below sea level. For instance, the North Sea had dried up, connecting the United Kingdom with continental Europe.

Up until the last glacial period, many species of megafauna roamed the globe, including mammoths, woolly rhinoceros, saber-toothed cats, glyptodons, cave bears, and giant deer (see Fig. 6). For reasons still debated, many of these animals went extinct as the ice retreated.

From around 45,000 years ago, early humans climbed their way through elaborate cave systems where they created awe-inspiring cave paintings, particularly of animals. The deeper parts of these caves are pitch black, and in order to find their way, these early humans made simple candles by burning animal fat in stone cups (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 – Lascaux candle (17,000 BC) (Semhur, CC BY-SA 4.0; Le Musée National de Préhistoire, France)

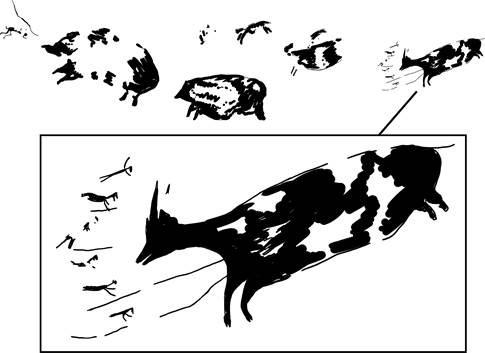

![]() The earliest cave art by Homo sapiens found thus far is from Indonesia

(as long as we don’t count man-made crosses scratched on a piece of ochre found

in a cave in South Africa, dated to about 77,000 years ago). In the caves of Maros-Pangkep,

we have found both the outlines of hands and what appears to be a hunting

scene, dating back to 44,000 years ago (see Fig. 8). The scene depicts what seem to be

human figures, although some have beaks and one has a tail. As we shall see in

a moment, human-animal hybrids were very common in early art.

The earliest cave art by Homo sapiens found thus far is from Indonesia

(as long as we don’t count man-made crosses scratched on a piece of ochre found

in a cave in South Africa, dated to about 77,000 years ago). In the caves of Maros-Pangkep,

we have found both the outlines of hands and what appears to be a hunting

scene, dating back to 44,000 years ago (see Fig. 8). The scene depicts what seem to be

human figures, although some have beaks and one has a tail. As we shall see in

a moment, human-animal hybrids were very common in early art.

Fig. 9 – Cave paintings from the replica Chauvet cave (32,000 – 28,000 BC) (Claude Valette, CC BY-ND 2.0; Grotte Chauvet 2, France)

A more advanced example of early cave art can be found in the Chauvet cave in France, dated to about 30,000 years ago (see Fig. 9). Notice the remarkable realism and dynamism with which these animals are portrayed. These cavemen-artists were not the barbarians they are sometimes presumed to be.

The most famous cave art was made in Lascaux, which is dated to about 17,000 BC. Inside this cave, we find images of bison, horses, bulls, rhinos, and other game animals that are drawn panoramically on the walls. Here too, the animals are portrayed in a surprisingly realistic style. In both Lascaux and other caves, a line of dots is sometimes found next to an animal. It was recently proposed that the number of dots corresponds to the mating season of the animals, measured in lunar months since spring time. If this discovery holds up, it is the first evidence both of the use of a rudimentary lunar calendar and of proto-writing.

Fig. 10 – The archeologist Abbe Breuil in the Hall of the Bulls in Lascaux (Wellcome Collection, CC BY 4.0; Lascaux, France)

Fig. 11 – Replica of the Bird-man from Lascaux (c. 15,000 BC) (Lascaux IV, France)

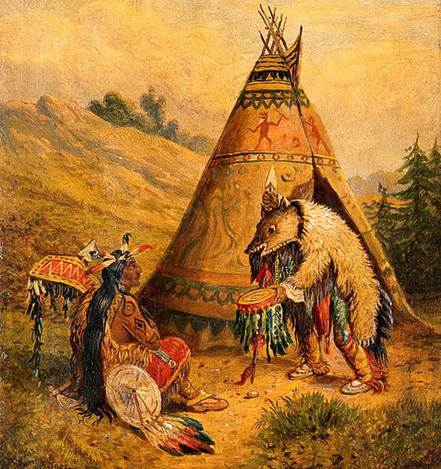

When we enter Lascaux, we first find ourselves in a large room, now called the Hall of the Bulls (see Fig. 10), with on the surrounding walls images of bulls, horses, and stags. The room converges toward a smaller tunnel also covered with beautiful animals, known as the Axial Gallery. Less obvious is the much smaller Passageway on the side. In the past, this opening was so small that people had to crouch down to enter. At the end of the Passageway, the path splits up once more. In one direction we end up in a narrow and long tunnel, at the end of which we find depictions of lions, some pierced with spears. In the other direction, the floor suddenly drops about 5 meters, leading to the Shaft. Today a ladder is installed to reach the bottom. Here we find something remarkable: an image of what appears to be a man wearing a bird mask next to a staff with a bird on top (see Fig. 11). For unknown reasons, this human figure is drawn much more abstractly than the animals. Although we will probably never know the true meaning behind this mysterious scene, many historians believe we are looking at the oldest image of a shaman. To this day, these magician-priests are integral to many hunter-gatherer tribes and often dress up as animals during rituals (see Fig. 12).

Fig. 12 – A Siberian shaman drawn by the Dutch explorer Nicolaes Witsen (17th century)

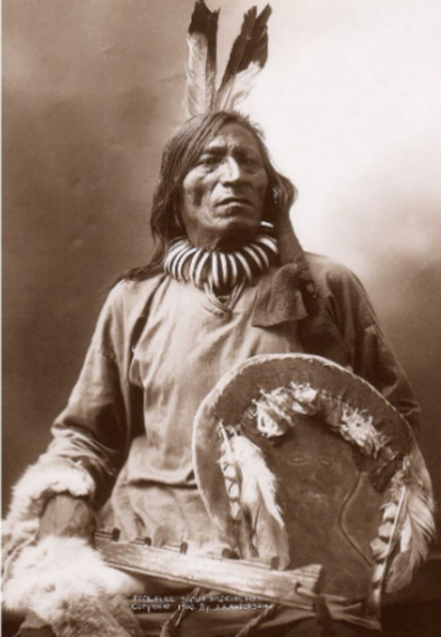

Fig. 13 – A Native American Sioux shaman (Friedrich Ratzel, 1896)

Fig. 14 – Two sketches by Abbe Breuil from the Trois Frères cave (13,000 BC). The antlers on the left sketch remain controversial, as it is possible that Breuil mistook natural cracks in the rocks for engravings (Trois Frères cave, France)

More evidence for this hypothesis comes from the Trois Frères cave system in France. In Fig. 14, we see two copies of engravings from deep in the cave. In the left image, we see a human-like figure with antlers, and to the right, we see a human-like figure dressed as a bison.

In addition, various bone flutes have been found in German caves, the oldest dating to about 42,000 BC (see Fig. 16). It is likely these instruments were not used for sheer entertainment, but also had some ritualistic purpose (as in many tribal cultures today).

Fig. 15 – The Lion Man made from mammoth ivory (40,000 – 35,000 BC) The head and paws are feline, yet the body and posture is human-like (Dagman Hollmann, CC BY-SA 3.0; Museum Ulm, Germany)

Fig. 16 – Vulture bone flute from Hohle Fels, Germany (c. 42,000 BC) (H. Jensen; University of Tubingen)

The story gets even more mysterious if we take into account how incredibly difficult it is to reach the deeper parts of some of the caves. An early researcher of the Trois Frères cave system, Dr. Herbert Kühn, described his descent into the cave as follows:

How magnificent the stalactites are! The soft drop of the water can be heard, dripping from the ceiling. There is no other sound and nothing moves. The silence is eerie. The gallery is large and long, and then there comes a very low tunnel. We placed our lamp on the ground and pushed it into the hole. The tunnel is not much broader than my shoulders, nor higher. I can hear the others before me groaning and see how very slowly their lamps push on. With our arms pressed close to our sides, we wriggle forward on our stomachs, like snakes. The passage, in places, is hardly a foot high, so that you have to lay your face right on the earth. I felt as though I were creeping through a coffin. You cannot lift your head; you cannot breathe.

And then, finally, the burrow becomes slightly higher. One can, at last, rest on one’s forearms. But not for long; the way again grows narrow. And so, yard by yard, one struggles on—some forty-odd yards in all. It is terrible to have the roof so close to one’s head. And it is very hard: I bump it, time and again. Will this thing ever end? Then, suddenly, we are through, and everybody breathes. It is like a redemption.

The hall in which we are now standing is gigantic. We let the light of the lamps run along the ceiling and walls: a majestic room—and there, finally, are the pictures. From top to bottom, a whole wall is covered with engravings. The surface had been worked with tools of stone, and there we see marshaled the beasts that lived at that time in southern France: the mammoth, rhinoceros, bison, wild horse, bear, wild ass, reindeer, wolverine, musk ox; also, the smaller animals appear: snowy owls, hares, and fish. And one sees darts everywhere, flying at the game. Several pictures of bears attract us in particular; for they have holes where the images were struck and blood is shown spouting from their mouths. Truly a picture of the hunt: the picture of the magic of the hunt! [1]

Entering this cave is such an effort that it is hard to believe that this art merely served as a means for creative expression. It seems reasonable to assume there must have been some deeper religious motivation—perhaps mimicking a descent into the underworld (a common motive among modern hunter-gatherer tribes) or perhaps these caves functioned as sacred spaces, similar to later temples and churches.

![]() Sculptures have also been found in some caves. In Fig. 18

we can see a sculpted bison from the Trois Frères cave system, dating to about

13,000 BC. Even older sculptures were found in German caves, including the

beautiful Lion Man from the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave and various

ivory animal statuettes from the Vogelherd cave, each from around 30,000

years ago (see Fig. 15 and Fig. 19).

Sculptures have also been found in some caves. In Fig. 18

we can see a sculpted bison from the Trois Frères cave system, dating to about

13,000 BC. Even older sculptures were found in German caves, including the

beautiful Lion Man from the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave and various

ivory animal statuettes from the Vogelherd cave, each from around 30,000

years ago (see Fig. 15 and Fig. 19).

Fig. 18 – A sculpted bison, from the Trois Frères cave system (13,000 BC) (Chatsam, CC BY-SA 3.0; Musée des Antiquités Nationales, France)

|

Fig. 19 – Sculpture of a horse, from the Vogelherd cave (c. 30,000 BC) (Wuselig, CC BY-SA 4.0; Museum der Universität Tübingen, Germany)

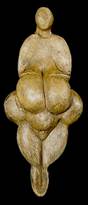

Inside the caves, but also in the campsites where these early humans lived, archaeologists have discovered various Venus figurines. These are small statues of the female figure. The figures frequently feature greatly exaggerated breasts and hips, and in various instances, the genitals are clearly marked out. Special attention was also given to the hair, while the faces were left blank. Given that all these features are associated with fertility, these figures have often been interpreted as early fertility symbols, representing woman in her role as life-giver (although perhaps they were simply “Stone Age pornography”).

Fig. 20 – The Venus of Willendorf (30,000 BC) (Bjorn Christian Torrissen, CC BY-SA 4.0; Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Fig. 21 – The Venus of Laussel (25,000 BC) (120, CC BY 3.0; Bordeaux Museum, France)

Fig. 22 – The Venus of Lespugue (reconstructed (26-24,000 BC) (Musée de l'Homme, France)

Fig. 23 – The Venus of Hohle Fels (35-40,000 BC) (Thilo Parg, CC BY-SA 3.0; Prehistoric Museum of Blaubeuren, Germany)

The burials of Homo sapiens also became much more intricate. Especially impressive are the burials at Sungir in Russia, from around 32,000 years ago. One of the graves contains the skeletons of two teenagers, placed head-to-head (see Fig. 17). Each of the skeletons was covered with about 5000 mammoth ivory beads, which were likely attached to their clothing and would have taken thousands of hours to make. The of them also has a belt containing 250 polar fox teeth (corresponding to about 60 foxes) and a small ivory statuette of a mammoth. Running parallel to both bodies was found a 2.4-meters-long straightened mammoth tusk. The fact that these children were singled out for such a lavish burial suggests a strong social hierarchy must have been in place among these people.

Modern tribes

We can also gain insight into the lives of early humans by studying still-existing tribal cultures. Of most interest to us are those cultures that have been living in isolation from the modern world. Surprisingly, these tribal cultures share similarities across the globe.

These tribes are made up of nomadic hunters and gatherers who generally travel in groups of ten to fifty, and occasionally up to one hundred people. This number is mostly constrained by the amount of game available to sustain a given tribe. Having to follow game animals from place to place, these tribesmen own few possessions and build no permanent houses. Although the hunt can be dangerous and uncertain, they often work fewer hours than modern people do.

Hunter-gatherer tribes are also known for their egalitarianism (although there are some exceptions, as we will soon see). In many cases, there is little status difference between the members of the tribe, and there are few privileges for specific members. Although a person with a special talent might take the lead when executing a task, there is no clear political leadership. This is surprising, especially since dominance hierarchies are the norm both in more complex societies and among chimpanzees. Understandably, there does exist a natural status difference between the elders and the younger tribe members based on years of experience. There also usually is a division of labor between men and women based on their different body types. In most cases, the women do most of the gathering, while men concentrate on big-game hunting. Yet, in many of these cultures, women are just as influential as men. In some cultures, shamans do have higher status and might enjoy some special privileges, such as a more elaborate funeral, but even these men are not village leaders and frequently have no political power.

These egalitarian traits have contributed to the myth that tribal cultures form utopian societies. Yet, when studied more closely, it turns out that the lack of a dominance hierarchy does not come automatically. It is often maintained by the males of the tribe, who work together to prevent any person from dominating others and from hoarding too many females. In extreme circumstances, tribes can go as far as killing a male who tries to take over. Tribal cultures are also notoriously violent, with murder rates significantly higher than in our inner cities. The murder rate is even large enough to have a significant impact on life expectancy. Even in the ancient cave paintings we see what seem to be humans pierced by spears and we have found skeletons from the same period with projectiles lodged in their bones. Raids between tribes were also common.

It also isn’t the case that these communities always lived in harmony with nature. In many cases, tribes had considerable impact on their environment. For instance, various tribes set fire to large forests to drive out game and some hunted animals to extinction.

Lately, some historians have pointed to a small number of hunter-gatherer societies from the past without egalitarianism. We have already seen evidence for this when we discussed the Sungir burials (see Fig. 17). The most remarkable example was documented by a Spanish boy named Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda, who was aboard a ship that stranded in Florida in 1549. The indigenous people killed everyone on board, except for the little boy, who continued to live with them until he was rescued 17 years later. From his memoir, we know that the natives, known as the Calusa, were part of a nation of 50 to 60 permanent villages spread over a huge area. They were able to settle down because of the abundant fish in the region. The leader of the Calusa had many of the characteristics we would normally associate with kingship. He ruled from a massive house, spacious enough to fit 2000 people, collected tribute from the villages under his control in return for protection, hosted lavish parties, and had enough control over his people to perform regular human sacrifices. He even had his people dig a four-kilometer-long canal.

The reason we do not find these permanent hunter-gatherer villages today is because there are only a few places on Earth were wild game is available throughout the year and because agricultural and industrial societies also took interest in these regions. It is not by choice that many modern-day tribes are found in barely habitable areas, such as the Kalahari Desert in South Africa.

Rituals

Most tribal cultures have developed a wide variety of rituals. Especially prominent in tribes around the world are the so-called puberty rites, also called rites of passage. The purpose of these rites is to help a boy make his transition into manhood. During these rituals, the child is initiated into the secret teachings of his culture, learns the values of the tribe, and becomes a responsible hunter and protector. To ensure a transformative and lasting experience, these rituals are often terrifying. For instance, in the puberty rite of the Australian Aranda tribe, a boy has designs painted on his chest and back, which are believed to be the marks of their mythological ancestors. With these marks, the boy is thought to become the living counterpart of his ancestors for the duration of the ritual. The Aranda ritual continues with events that include dancing, singing, and intense shouting. Then the boy is brought into the forest, where he is left alone and has to sit quietly for three days with little to eat. Once back home, the boy hears an instrument called a bullroarer, which is a flat piece of wood that creates a roaring noise when swung around. During his childhood, he was told that this was the sound of a terrifying spirit. The tribesmen then convince the boy that this spirit is temporarily entering his body. He is then circumcised and bullroarers are placed against the wound. The boy is subsequently offered one of the bullroarers, which is presented as a sacred object. From that moment on, his dependency on his mother has ended. He can no longer play with the girls or gather food with the women. Instead, he has to join the men and hunt kangaroo. [2]

Fig. 24 – The Aranda tribe during a ritual (W. Baldwin and F. Gillen, 1901, Australia)

Although this example is specific to the Aranda tribe, many common elements appear in rites of passage across the world. One common motive is seclusion, often with little to eat. Scarification is another common theme, here in the form of circumcision, which serves as a physical reminder of the transformation. Another common feature is drumming and chanting, often combined with participants wearing masks to identify themselves with spirits. These rituals induce trance states, which can heighten the senses and make participants extremely suggestible. In these states, various seemingly “supernatural” acts can be performed, such as anesthetizing parts of the body or inducing seizures, which in recent decades have been replicated in universities using hypnosis. With all these effects combined, these rites cause intense distress, which deepens the character of the participant, making him ready to take on the responsibilities of an adult.

Puberty rites for girls are connected to their first menstruation, which is nearly universally treated as a taboo, associated with uncleanliness and danger, yet also with the creation of life. In various cultures girls are hidden away from society during their first menstruation in a so-called menstruation hut. They are also often restricted from performing certain tasks, often for fear of “pollution.” In various tribes in southern India, for instance, girls on their period were not allowed to touch the earth or see the sky. On the island of Wogeo, New Guinea, girls were not allowed to eat with their fingers or touch their bodies. [3] During their period, girls are typically cared for by their mother and other elder women of the tribe and are introduced to the biological changes, traditions, and responsibilities of womanhood. After menstruation is over, the girl generally washes herself before she returns to the village, where she is paired with the man who will become her husband. At this point, she is deemed ready for childbearing and is recognized as a woman by the community.

Fig. 25 – American Indian medicine man performing a ritual dance (George Catlin, 19th century; Wellcome Collection; CC BY 4.0)

Another common ritual is meant to ensure the continued availability of food. Among the Australian Warlpiri, for example, each family is assigned a species of animal or plant and has to carry out a ritual to ensure that all the food that gets eaten is replenished the next season. In some cases, these rituals also contain a rationale that makes the killing of animals morally tolerable. Among various Native American tribes, for example, it is believed that animals give their lives willingly in exchange for a ritual which ensures these animals will be reborn the next year. This belief turns the hunt from murder into a sacred activity.

Let’s illustrate this with a story from the Cherokee Indians. One day, a man left his tribe to hunt bear in the mountains. When he found a huge bear, he shot arrow after arrow at it, but the bear simply pulled the arrows out of his body. The bear then told the hunter not to waste any more arrows since he was not an ordinary bear but a medicine bear who could not be killed. The bear then invited the man to go with him and spend the winter together. During that time, the man learned the ways of the bear and even grew fur.

In the spring, the bear told the man that his tribe was about to get ready for the hunt and that they would kill him. He then taught the man a ritual to ensure he would not remain dead forever. The man did what was asked of him. We read:

Before they left, the man piled leaves over the spot where they had cut up the bear, and when they had gone a little way, he looked behind and saw the bear rise up out of the leaves, shake himself, and go back into the woods. [4]

This story powerfully exemplifies how closely connected these tribal people were to the animal kingdom. They don’t share the modern notion that human beings are distinct from animals, let alone superior to them. In fact, the bear in the story was himself a master-shaman, while the man was merely his apprentice. This is not such a far-fetched notion as one might think, considering that in the wild, learning from animals is an important part of survival. Through natural selection, animals have found their way in nature in surprisingly clever ways. Hence, copying their habits and following their trails can help with finding food or avoiding danger. Also, many animals have superhuman powers. Some can see in the dark, others can achieve incredible speed, have incredible strength, or can even fly.

The Blackfoot Indians of North America have a similar story. A Blackfoot tribe hunted buffalo by luring them over a cliff. One day, however, this method stopped working, and the people began to starve. Out of desperation, a girl from the tribe said she would marry a particular buffalo if the others would jump over the cliff. To her surprise, they jumped, after which the buffalo took her by the arm and brought her with him. When the father of the girl managed to find her, the buffalo trampled him with his hoofs until he died. When the girl mourned the death of her father, the buffalo reminded her that human beings did the same to his own species. The buffalo then told the girl he would let her go, but only if she could bring her father back to life. The girl then sang a magical song, which did the trick. In return, the buffalo taught the girl a song and dance to bring his species back to life as well. During the dance, the tribesmen were required to put buffalo skulls on their heads and wear their fur as robes. She was told never to forget what she had learned because, through this rite, humans and buffalo could live in harmony.

The spiritual world

Although the natural world is often harsh, tribal cultures also speak of a spiritual beauty inhabiting all of nature. To them, everything on earth is sacred and filled with spirits. These spirits were believed to inhabit everything around them, including lakes, rivers, trees, unusual rock formations, and even gusts of wind. The comparative anthropologist Sir James Frazer collected countless accounts of how cultures around the world interacted with these spirits. Regarding the curious example of wind spirits, he wrote:

It is still said of the Bedouins of Eastern Africa that “no whirlwind ever sweeps across the path without being pursued by a dozen savages with drawn [daggers], who stab into the center of the dusty column in order to drive away the evil spirit that is believed to be riding on the blast.” [5]

Similarly, we read that the Payaguá from South America run against the wind with torches, while others beat the air with their fists to frighten the storm. In Scotland, Frazer noted, sailors still “buy winds from old women who claim to rule the storms.” These are just a few examples of the many superstitions recorded by anthropologists.

Some spirits are also believed to live in a heavenly realm, which is another common motif across the globe. Take, for instance, the Kalapalo of Brazil. They speak of “powerful beings” that live in a “Sky Village.” Shamans are believed to visit this place during their trances, and people are believed to go there after death. [6]

Unlike our modern conception of God, the spirits from tribal mythologies are generally not inherently good or evil. They do not judge our actions based on a moral code and do not punish or reward in the afterlife. Instead, their actions are seen as powerful energies that can both help and harm mankind. Just like nature, these forces are the source of both beauty and terror. This duality of nature is beautifully demonstrated in the following myth from an East-African tribe:

The tale is of a young man whose dead father appeared to him, driving the cattle of Death. The father led him along a path going into the ground. They came to an area with many people, where the father hid his son and left him. In the morning, the Great Chief Death appeared. One side of him was beautiful, but the other rotten, with maggots dropping to the ground. Attendants were gathering up the maggots. They washed the sores and, when they had finished, Death said, “The one born today will be robbed if he goes trading. The woman who conceives today will die with the child. The man who works in his garden will lose the crop. The one who goes into the jungle today will be eaten by the lion.”

But the next morning, Death again appeared, and his attendants washed and perfumed the beautiful side, massaging it with oil, and, when they had finished, Death pronounced a blessing. “The one born today: may he become rich! May the woman who conceives today give birth to a child who will live to be old! Let the one born today go into the market: may he strike good bargains; may he trade with the blind! May the man who goes into the jungle slaughter game; may he discover even elephants! For today, I pronounce the benediction.” [7]

In many tribes, ritual is used to channel both the destructive and beneficial forces of nature in the right direction. The Kalapalo, for instance, use music and song to communicate with the spirits and to calm them down when they get angry.

Another important distinction between tribal mythology and later religions is the absence of prayer and worship. It is this absence that makes us refer to these beings as spirits rather than gods. Instead of worshipping a spirit, tribal people generally identify with them during their rituals. The tribesmen become the spirits, which is sometimes called mythic identification. Through dance, music, and storytelling, they embody the spirits’ magical powers and wield their energies for some gain, such as to find food, cure sickness, obtain advice, foresee the future, or kill enemies.

Shamans

Among many tribes across the world, we find mysterious characters called shamans. A shaman is a seer who can experience the spirit world through visions and hallucinations. These visions often come during dreams, but they can also be induced by rhythmic drumming, chanting, and dancing, sometimes in combination with the use of psychedelic drugs.

The West became aware of these figures when a dissident Russian priest named Avvakum was exiled to Siberia in the 1650s, where he came to live among the reindeer-herding Evenki. From his descriptions, and from those of later missionaries, travelers and exiles, the West became acquainted with the spirit-filled world described in the previous paragraph. Some special individuals among the Evenki were called “saman” (from which we derive the word “shaman”), which roughly translates as a “person with supernatural skill.” These samans contacted the spirit world to cure sickness and increase the success of the hunt. To achieve this, the samans would enter a state of trance until their souls left their bodies and flew towards the spirits. Through these flights, the samans documented the cosmos for their fellow hunter-gatherers. To them, the world was a three-layered cake with heaven above and an underworld below ground. When the Siberian Tungus were asked how they knew about the three-layered cosmos, they simply responded: “So the samans say.” [8]

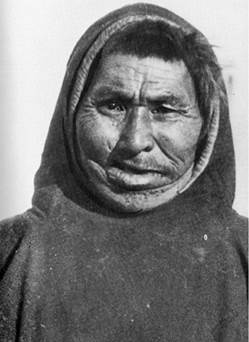

Fig. 26 – A Mongolian shaman (c. 1909) (National Museum of Finland).

Fig. 27 – An Alaskan shaman exorcising an evil spirit from a sick boy (Library of Congress)

Fig. 28 – A Sioux medicine man called Fool Bull, or Tatanka Witko (John Anderson, 1900)

The samans often dressed extravagantly in accordance with their supernatural nature. They wore impressive headgear and coats, adorned with fur, feathers, jingling amulets, and figurines, and often carried a drum to produce trance-inducing rhythms. To distinguish themselves from the rest, they also tended to live on the edges of their community, or even outside it. They also often adopted a different lifestyle. For instance, some avoided certain foods or various activities such as sex. In various cases, the samans were also distinguished by a physical anomaly or by flexibility in their gender.

All these characteristics of the saman were later found in tribes across the world, with examples found on every continent. It is hard to explain these similarities without assuming they represent a human universal. Somehow, throughout our evolution, the strange experiences of the shaman—including the flight of the soul and contact with spiritual entities—were ingrained into our DNA and became part of what it means to be a human being. In modern experiments with hallucinogens, participants also often report sensations of flying, transformations into animals, encounters with spirits, the perceived transmission of wisdom, and revelations concerning a universally shared life force.

Let’s now discuss soul flight in some more detail. In various accounts, we hear of shamans in their trance flying to heaven, sometimes flying on their drums. Some shamans also attached feathers to their coats to highlight this ability (see Fig. 29). Heaven isn’t the only destination. Other shamans travel to the underworld. They might go underwater, enter a cave, or go down animal burrows into the ground. Take, for example, a story of the Inuit about the goddess Sedna, who lives on the bottom of the sea. She was believed to be responsible for sending new fish every year for the Inuit to eat. When there wasn’t enough food, a shaman would enter a trance so that his soul could travel to the bottom of the sea, where he calmed the goddess down with a magical song until she agreed to release new fish for the people.

On their spiritual journey, shamans are also often helped by spirit guides, who may appear in human or animal form. The shaman himself is sometimes believed to have transformed into an animal. Not surprisingly, given these superstitions, tribesmen who stumble on an unusual animal are easily convinced that they have encountered either a shaman on one of his astral journeys or a spirit guide.

During their trances, shamans also report defeating spiritual monsters, stealing precious items from the spirits, accompanying the soul of a deceased person to heaven, winning the favor of a spirit, or gaining insight into both past and future. The most common purpose for their magical journeys is to find a cure for either sickness or madness. It is a common tribal belief that these afflictions are caused by either a departure of the soul from the body or the entrance of a foreign spirit or negative energy. To counteract this, the shaman has to either retrieve the soul or perform an exorcism.

Today, we may dismiss “encounters” with spirits as “mere” psychological phenomena, yet it is nonetheless striking how confidently some shamans can navigate the still mostly unexplored symbolic realm of dreams and visions. Some shamans even display schizophrenic symptoms, which they can manage without succumbing to full-blown psychosis.

Fig. 29 – Copy of a Niukzha rock art panel from Siberia. A shaman with wings is depicted between the birds and the stars (date unknown) (The Archeology of Shamanism, Ekaterina Devlet, 2001)

South American shamans are particularly known for their use of powerful hallucinogens to contact the spirit world. Evidence for the use of ayahuasca in the Amazon dates back to at least a thousand years ago, the San Pedro cactus in Peru to about two thousand years ago, and peyote in Mexico and Texas to at least 3800 BC. Ayahuasca, in particular, is known to induce both heavenly and hellish visions. While modern science dictates that these visions are caused by chemicals that interact with our brain, shamans instead believe these plants open them up to the spiritual realm, which is to them at least as real as the material world. Encounters with visionary snakes, including giant mythological ones, are particularly common with ayahuasca. Given our natural fear of snakes, this requires shamans to overcome a deep-seated fear. But if the shaman manages to stay calm and in control, he might even become the snake’s apprentice and take on some of its dangerous powers. For this reason, shamans across the world often associate themselves with dangerous and powerful animals, including bears and felines.

Shamanism has also been extensively researched among the San people of South Africa. We have detailed accounts from anthropologists starting in the 19th century and we have hundreds of rock paintings, which have been dated from anywhere between 3000 years ago to relatively recent. The |Xam San, for instance, speak of a type of magical energy, called !gi, which the shape-shifting trickster-deity |Kaggen was believed to have given to humankind and that resides in great animals, especially the eland. The shamans among the San people were masters of !gi and were therefore called !gi:xa (meaning “full of !gi”). Unusually, shamanism is not rare among the San people. About half of the men are shamans and about a third of the women. The task of the shaman is to cause the !gi to boil up in their spines until it explodes in their heads, at which point the shaman loses consciousness, falls to the ground, and trembles violently, while his spirit takes off to the spirit realms (see Fig. 30). This is induced not by hallucinogens, but through continuous dancing, singing, and swift shallow breathing. When the shaman falls to the ground, he is said to have died. In their words, “It is the death that kills us all, [but] healers come alive again.” During this time, the shaman is believed to be in great danger, as his soul might get lost or get captured by evil spirits. Their spiritual death does give them great sight, allowing them to see the magical !gi energy, illnesses in their patients, and also things that happen at great distances. [9]

In Fig. 31 we see a rock painting depicting their dance. Dancers bend forward as their stomach muscles contract and some bleed from the nose. They are also surrounded by specks of supernatural !gi. Some images also show a rope, which they claim is only visible to the shamans and allows their soul to climb to heaven.

Fig. 30 – A San shaman has passed out, while the women of the tribe take care of him (1959) (Jurgen Schadeberg)

In special curing sessions, a San shaman goes into a trance, sees into the body of a patient, draws out the illness into his own body, which they then expel with a wild shriek through an imaginary hole in the back of their neck.

Interestingly, the paintings themselves were described as more than just depictions. The paint itself was mixed with sacred eland blood and the paintings were believed to emit magical energy. It is possible that the ancient cave paintings we discussed earlier in this chapter had a similar function.

Fig. 31 – A copy of San rock art depicting a trance dance (African Rock Art Digital Archive, RSA HAE1)

Fig. 32 – A copy of San rock art depicting a healing ritual (African Rock Art Digital Archive, RSA LNR1)

Becoming a shaman

Not every boy (or girl) of a tribe is destined to become a shaman. It is often believed that the spirit realm selects who will become a shaman by sending remarkable dreams, visions, or hallucinations. Once chosen, the shaman-to-be will undergo a special initiation rite. This might involve a monstrous ritual that pushes him to the edge of death. The shaman goes alone into a dark forest or to the top of a mountain, where he stays for days with little or nothing to eat. The extreme deprivation is supposed to induce a vision, either in dream or in the waking state, in which a spirit guide appears in either human or animal form. Unlike the often-scripted rituals of later religions, these visions are unique personal experiences that often become central to a shaman’s life. The spirit guide usually imparts wisdom, which can become part of the mythology of the tribe. A chieftain of the Sioux Indians described this process as follows:

From Wakan-Tanka, the Great Mystery, comes all power. It is all from Wakan-Tanka that the Holy Man has wisdom and the power to heal and to make holy charms. […] To the Holy Man comes in youth the knowledge that he will be holy. The Great Mystery makes him know this. Sometimes it is the Spirits who tell him. The Spirits come not in sleep always, but also when man is awake. When a Spirit comes, it would seem as though a man stood there, but when this man has spoken and goes forth again, none may see whither he goes. With the Spirits, the Holy Man may commune always, and they teach him holy things. The Holy Man goes apart to a lone tipi and fasts and prays. Or he goes into the hills in solitude. When he returns to men, he teaches them and tells them what the Great Mystery has bidden him to tell. He counsels, he heals, and he makes holy charms to protect the people from all evil. Great is his power and greatly is he revered; his place in the tipi is an honored one. [10]

The Inuit shaman Igjugarjuk described his initiation as follows:

Strange unknown beings came and spoke to him, and when he awoke, he saw all the visions of his dream so distinctly that he could tell his fellows all about them. Soon it became evident to all that he was destined to become an angakoq [a shaman]. No food or drink was given to him; he was exhorted to think only of the Great Spirit and of the helping spirit that should presently appear—and so he was left to himself and his meditations. Toward the end of the thirty days, there came to him a helping spirit in the shape of a woman. She came while he was asleep and seemed to hover in the air above him. After that, he dreamed no more of her, but she became his helping spirit. [11]

In reports, we often read how these tough initiations help strengthen the shaman’s character, giving him a practical wisdom that is hard to gain in any other way. About this, Igjugarjuk said:

The only true wisdom lives far from mankind, out in the great loneliness, and it can be reached only through suffering. Privation and suffering alone can open the mind of man to all that is hidden to others. [12]

This makes encounters with shamans often an intense experience. Their acquired wisdom could often be seen in their eyes. According to the Chukchee of Siberia, the “eyes of a shaman have a look different from that of other people. […] The eyes of the shaman are very bright, which, by the way, gives them the ability to see spirits even in the dark.” Similarly, the San shamans can instill fear in people “because [their] eyes […] shine like a beast-of-prey’s.” The anthropologist Peter Elkin, in 1945, observed that the Aboriginals with their “shrewd, penetrating eyes […] look you all the way through […] photographing your very character and intentions.” “I have seen those eyes and felt that mind at work when I have sought knowledge that only the man of high degree (the shamans) could impart. I have known white people who almost feared the eyes of a karadji [shaman], so all-seeing, deep, and quiet did they seem.” [9]

Charlatans or guardians of truth

Shamans are often feared for their magical powers, but tribesmen can also turn against them if their magic fails to work or if some inexplicable evil occurs. For instance, if a young man dies without any apparent cause, shamans in some tribes have to fear for their lives. To keep up appearances, shamans often use cheap tricks and mysterious rhetoric to persuade their fellow tribesmen of their powers. In one instance, a shaman was observed sucking on the body of a tribesman to draw out a malevolent presence. When faced away from the onlookers, he quickly placed a mouse in his mouth and then pretended to have sucked it out of the body. This act was accompanied by theatrical gestures and sounds. In some cases, the magic was so good it even fooled the anthropologists. As the explorer Lucas Bridges recalled when he met the shaman Houshken of the Ona tribe from Tierra del Fuego, South America:

Houshken broke into a chant and seemed to go into a trance, possessed by some spirit not his own. Drawing himself up to his full height, he took a step towards me and let his robe, his only garment, fall to the ground. He put his hands to his mouth with a most impressive gesture and brought them away again with fists clenched and thumbs close together. He held them up to the height of my eyes, and when they were less than two feet from my face, slowly drew them apart. I saw that there was now a small, almost opaque object between them. It was about an inch in diameter in the middle and tapered away into his hands. It might have been a piece of semi-transparent dough or elastic, but whatever it was, it seemed to be alive, revolving at great speed, while Houshken, apparently from muscular tension, was trembling violently. The moonlight was bright enough to read by as I gazed at this strange object. Houshken brought his hands further apart and the object grew more and more transparent, until, when some three inches separated his hands, I realized that it was not there anymore. Houshken made no sudden movement, but slowly opened his hands and turned them over for my inspection. They looked clean and dry. He was stark naked and there was no confederate beside him. [13]

The same anthropologist who spoke to Igjugarjuk, Knud Rasmussen, brought the shaman Najagneq to a modern city for the first time. When Najagneq returned, he used his new experience to convince his fellow tribesmen of his magical abilities:

He was not at all impressed by the large houses, the steamers, and the motor-cars. But he had been fascinated by the sight of a white horse hauling a big lorry. So, he now told his astonished fellow villagers that the white men in Nome had killed him ten times that winter, but that he had had ten white horses as helping spirits, and he had sacrificed them one by one and thus saved his life. [12]

When alone with the anthropologist, however, Najagneq admitted he had lied to his fellow tribesmen to stay out of trouble. But whenever they discussed his old visions and his ancestral beliefs, he turned serious. When asked whether he believed in any of the powers he spoke of, he answered earnestly:

Yes, a power that we call Sila, one that cannot be explained in so many words; a very strong spirit, the upholder of the universe, of the weather, in fact of all life on earth—so mighty that his speech to man comes not through ordinary words but through storms, snowfall, rain showers, the tempests of the sea, all the forces that man fears, through sunshine, calm seas, or small, innocent playing children who understand nothing. When times are good, Sila has nothing to say to mankind. He has disappeared into his infinite nothingness and remains away as long as people do not abuse life but have respect for their daily food. No one has ever seen Sila. His place of sojourn is so mysterious that he is with us and infinitely far away at the same time. [12]

About this mysterious being, he also said:

The inhabitant or soul of the universe is never seen: its voice alone is heard. All we know is that it has a gentle voice, like a woman, a voice so fine and gentle that even children cannot become afraid. What it says is: “be not afraid of the universe.” [12]

When asked how he had learned all this, he said:

I have searched in the darkness, being silent in the great lonely stillness of the dark. So, I became an angakoq (shaman), through visions and dreams and encounters with flying spirits. In our forefathers’ day, the angakoqs were solitary men; but now they are all priests or doctors, weather prophets or conjurers producing game, or clever merchants, selling their skill for pay. The ancients devoted their lives to maintaining the balance of the universe; to great things, immense, unfathomable things. [11]

Fig. 33 – The Inuit shaman Najagneq

The trickster

One of the great heroes of tribal mythology is the trickster figure. This figure is often celebrated for his great deeds, such as aiding in the creation of the world, regulating the course of the sun, slaying monsters, introducing various plants and animals to the world, and so on. They might also steal fire from the gods for the benefit of mankind, a motive we find in cultures across the world. At the same time, the trickster is also an impulsive clown who resorts to deceit to get what he wants. Although his trickery is sometimes successful, it mostly backfires. The book American Indian Trickster Tales describes the figure as follows:

Always hungry for another meal, swiped from someone else’s kitchen, always ready to lure someone else’s wife into bed, always trying to get something from nothing, shifting shapes (and even sex), getting caught in the act, ever scheming, never remorseful. Tales in which the lowly and apparently weak play pranks and outwit the high and mighty have delighted young and old all over the world for centuries. [14]

The trickster also regularly flouts social conventions, breaks taboos, and defies sacred authority. He is also frequently responsible for the appearance of evil in the world. In some stories, a trickster makes mistakes during the creation of the universe, bringing disease and death into the world. In other stories, he inadvertently ruins the work of a more competent creator. For example, the African trickster Eshu (see Fig. 34) gave the creator palm wine, leading him to create albinos and people with disabilities. Despite all these negative attributes, the trickster is not an inherently malicious character. In fact, he is often portrayed as a lovable, and sometimes even as a hero or a sacred being. Even Eshu was considered a hero as he had also taught mankind how to sacrifice to the spirits to keep them from harming humanity.

Wakdjunkaga, meaning “the tricky one,” is a prominent Native American trickster. One story describes him as a chief about to go to war. Before departing, he violated many social taboos, including leaving a feast before it was over and having sex the day before battle. On his way to the battleground, he made so many mistakes that all his soldiers abandoned him. Like many tricksters, he then became a solitary wanderer.

In one of his many ridiculous stories, a squirrel made fun of his penis, which was extremely large. In fact, it was so large, that he had to carry it in a box on his back. Wakdjunkaga wanted to catch the squirrel, but it hid in a hole in a tree. To get the squirrel out, he pushed his penis into the hole, after which the squirrel bit off pieces of his penis until it was of normal human size. The pieces then fell to the ground and became new edible plants for the community.

After his many adventures, Wakdjunkaga gave up his mischief and traveled down the Mississippi, clearing it of obstacles for travelers. He then ascended to heaven, where he was put in charge of the underworld. [15]

Tricksters can also appear in animal form. The Native Americans chose animals that live alone, such as Raven, Hare, and Coyote (as opposed to the crow, the rabbit, and the wolf, who hunt in groups). These animals were also known for their wit. For instance, ravens sometimes seem to play tricks on other animals, and coyotes are known to dismantle traps and steal the animals caught inside.

In one story, a powerful being stole the sun and the other celestial lights and kept them in a box. As a result, the earth turned pitch black, and nobody could find their way. Raven embarked on an adventure to retrieve these lights. At one point, he found the house of the being, but it was locked on all sides. When the being’s daughter went to a nearby river for water, Raven transformed himself into a speck of dirt and floated on the water. The daughter drank him up and became pregnant. Once Raven was born, he convinced the being to let him play with the box. After gaining access to it, he morphed back into a raven, flew through the smoke hole of the house, and released the lights back into the sky. [15]

In another story, a creator spirit placed stars on the desert floor before positioning them in the sky. He carefully drew out a map of where he wanted to place them, arranging them in patterns to guide travelers. At some point, Coyote grew impatient, picked up the remaining stars, and flung them randomly across the sky, thus forming the Milky Way.

In Polynesia, the most renowned trickster is called Maui. Like many tricksters, he is credited with stealing fire from the gods for the benefit of mankind. He is also believed to have invented the harpoon, hooks, and fishing nets. In one story, he pushed the sky away from the earth, giving people room to move around. In another story, he fished up the islands of New Zealand from the bottom of the sea. He is also said to have slowed down the sun, which traveled to quickly across the sky. Due to its speed, the days were so short that his mother had no time to make clothes and prepare food. To solve this problem, Maui made a lasso, threw it around the sun, and tugged on it to slow it down, creating the current length of our day. Yet, despite all these heroic deeds, Maui broke nearly every taboo of his culture. He had sex with his mother, killed many of his uncles, and played tricks on the spirits. In one story, he had an affair with the wife of a mighty eel called Tuna. In retaliation, the eel sent tidal waves. When the two met in battle, Maui killed the great eel and planted its head at a corner of his house. In time, green sprouts emerged from the spot, which grew into the first coconut tree. [15]

Characteristic of tricksters, the African trickster Eshu showed little concern for mankind. Like a force of nature, he acted without either malice or goodwill. He simply followed his impulses, often for the sheer joy of it. We read:

One day, this odd god came walking along a path between two fields. He beheld in either field a farmer at work and proposed to play the two a turn. He donned a hat that was on the one side red but on the other white, so that when the two friendly farmers had gone home to their village and the one had said to the other, “Did you see that old fellow go by today in the white hat?” the other replied, “Why, the hat was red.” To which the first retorted, “It was not; it was white.” “But it was red,” insisted the friend, “I saw it with my own two eyes.” “Well, you must be blind,” declared the first. “You must be drunk,” rejoined the other. And so the argument developed and the two came to blows. The friends quarreled for the first time in years. When they began to threaten each other with knives, they were brought by neighbors before the headman for judgment. Eshu was among the crowd at the trial, and when the headman sat at a loss to know where justice lay, the old trickster revealed himself, made known his prank, and showed the hat. He told them that neither of them were lying, but both of them were fools. “The two could not help but quarrel,” he said. “I wanted it that way. Spreading strife is my greatest joy.” [16]

When the chief sent officers after him, Eshu fled, setting several houses on fire along the way. Fortunately, the residents managed to rescue some of their possessions. Eshu promised to keep an eye on them while they were putting out the fire, but instead of keeping his word, he gave their belongings away at random, making some people happy and others sad.

Fig. 34 – A wooden figure of the African trickster Eshu from Nigeria (c. 1900) (Wellcome, CC BY 4.0)