In Egypt, pharaohs ruled not over single city-states, but over an entire nation. Unlike Mesopotamia, where kings were seen as servants of the gods, the pharaohs were considered gods themselves, worthy of gigantic pyramids, which they believed would help them safely reach the underworld after death. Architecture, not only in the form of pyramids, but also of temples and tombs, became the highlight of the Egyptian civilization, both in terms of its beauty and its massive scale.

In the 15th and 14th centuries BC, Egypt became a main player in the world’s first extensive international trading network. They traded with Mesopotamians, Hittites (Turkey), Minoans (Crete), Mycenaeans (mainland Greece), Canaanites (Israel), and others. This system collapsed in the 12th century, leading to the destruction of many cities and even entire civilizations.

Fig. 105 – Redrawing of the relief on the so-called Scorpion Macehead, showing men working on a canal, supervised by a king holding a hoe. (3200–2000 BC) (Krzysztof Cialowicz)

Osiris and the Nile

The Egyptian civilization would not exist without the Nile, whose annual flooding created extremely fertile soil. Unlike the Euphrates and the Tigris, the flooding of the Nile is remarkably regular, and therefore dependable, which helped to create steady surpluses of wheat to feed the population. These surpluses also made it possible for Egypt to enjoy long periods of security (again in stark contrast to Mesopotamia, where wars were frequent). When the water finally retreated, the hot Egyptian sun would quickly dry the soil. To solve this problem, canals and reservoirs were dug to retain the water longer. In some places, the water of the Nile was even channeled through copper pipes to homes, gardens, and palaces.

Mythologically, the regularity of the Nile was connected to the abstract concept of Maat, which stood for the divine order in the universe. Maat was also personified as a goddess who was deemed responsible for establishing order in the cosmos, regulating the motions of the stars, the seasons, and even the orderly functioning of society—which also made her a goddess of justice and morality.

Fig. 106 – Anubis mummifies a deceased person from the Theban tomb of Sennedjem (13th century BC) (Ignati, PD)

The water of the Nile would rise in July, around the same time that the star Sirius, the brightest star in the northern sky, became visible over the horizon. The star was related to the god Osiris, who was believed to have taught the Egyptians agriculture. Like many grain gods since the Neolithic, Osiris was a dying-and-resurrecting vegetation god. His main myth was first found in the Pyramid Texts, a funerary text written on the walls of burial chambers from the 24th century BC. The text consists of magical spells intended to ensure a pharaoh would get to the next world safely. The myth goes as follows. Osiris was the first king of Egypt, but was murdered by his brother Seth. Isis, Osiris’s wife, located his body, became pregnant, and gave birth to their son, Horus (see Fig. 107). Angered by this, Seth cut Osiris’s body into pieces and scattered them across the land. When Isis located the pieces, the god Anubis mummified the body, allowing him to “rise up” and become god of the dead (see Fig. 108) [26]. When Horus matured, he faced Seth in battle and defeated him, after which he was declared the new king of Egypt. Based on this myth, it was believed that every living pharaoh was an incarnation of Horus and every dead pharaoh an incarnation of Osiris.

The cutting up of Osiris’s body was connected to the cutting of grain during harvest, the impregnation of Isis was related to the planting of seeds, and the birth of Horus to the renewed growth of vegetation during spring. The link between Osiris and the growth of grain is depicted in Fig. 109, where we see sprouts coming from his mummified body. The Egyptians also created corn mummies, which were miniature mummies in the form of Osiris, filled with soil and seeds, and placed in a wooden coffin (see Fig. 110). These coffins were buried underground, and in time, grain would rise from the mummy and sprout from the earth, symbolizing the resurrection of Osiris. [26]

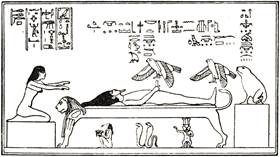

Fig. 107 – Redrawing of a relief from the Osiris chapel on the roof of the Hathor Temple at Dendara, showing Iris descending on Osiris in the form of a bird (Ptolemaic or early Roman period) (E Wallis Budge, 1910)

Fig. 108 – Redrawing of a relief from the same site showing Osiris resurrecting (Ptolemaic or early Roman period) (A. Mariette, 1870)

Fig. 109 – Redrawing of a relief from the Osiris chapel on the roof of the temple of Isis at Philae showing grain growing from the mummified body of Osiris (in the form of Neper, the god of grain) (Ptolemaic or early Roman period) (E. Wallis Budge, 1910)

Fig. 110 – A corn mummy (664-30 BC) (Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0 1.0)

The First Dynasty

Agriculture spread from Mesopotamia around 6000 BC, allowing villages to appear all over Egypt. Sometime in the second half of the fourth millennium BC, Egypt came to be ruled by two kings, one in Upper Egypt (confusingly located in the south) and one in Lower Egypt (in the north). Kings of Upper Egypt wore a white crown and those of Lower Egypt a red crown. This all changed around 3200 BC, when King Narmer of Upper Egypt conquered the north. Symbolizing this double rule, the two crowns were combined into one (see Fig. 111). Narmer became the first pharaoh of the First Dynasty of Egypt, initiating the Old Kingdom period of Egyptian history.

Fig. 111 – Left: The White Crown of Upper Egypt. Middle: The Red Crown of Lower Egypt. Right: The Double Crown of unified Egypt (Kompak, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Fig. 112 – The Narmer Palette (c. 3200 BC) (Wikimedia; Cairo Museum, Egypt)

Narmer’s success was documented on the Narmer Palette (see Fig. 112). On the front side, Narmer is holding an enemy by the hair, while holding a mace in his other hand. On the other side, we see a victory procession and a number of headless bodies.

During the First Dynasty, pharaohs were buried in simple mud-brick tombs. Unfortunately, their tombs were all robbed long ago, so we know little about what was inside of them. We do know that these early pharaohs often had two tombs attached to their name, one in the south at Abydos (where Osiris was buried according to legend) and one at Saqqara, in the north. Perhaps this double burial symbolized their leadership over both parts of Egypt.

Fig. 113 – The Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, Egypt (c. 2650 BC) (Vyacheslav Argenberg, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Fig. 114 – Columns in the courtyard of Djoser’s pyramid (c. 2650 BC) (Sebi)

Fig. 115 – A building on the courtyard of Djoser’s pyramid (c. 2650 BC) (Neithsabes)

The Great Pyramids

Little is known about the Second Dynasty of Egypt. The Third Dynasty, however, was spectacular. The first pharaoh of this dynasty was Djoser (27th century BC), the first pyramid builder. It is commonly believed that the first pyramid was designed by Imhotep, chancellor to the pharaoh and high-priest of the sun god Ra. This attribution, however, is solely based on an inscription that states “Imhotep, the builder.” Only during Greek times did the legend form that made Imhotep the architect of the first pyramid.

The pyramid of Djoser still stands today and is a so-called step pyramid with an impressive height of 60 meters (see Fig. 113). It was the first large project in Egypt where limestone was used as the primary building material instead of mud-brick. Stunningly, the burial chamber inside the pyramid was made of granite from the quarries of Aswan, about 900 km to the south.

The pyramid does not stand alone in the desert, but is part of an entire walled courtyard with various buildings, some containing beautiful stone columns (see Fig. 114 and Fig. 115).

Pharaoh Sneferu (26th century BC), the founder of the Fourth Dynasty, built three pyramids. The first was the Meidum Pyramid, which is so steep it looks more like a tower than a pyramid (see Fig. 116). The second one was the Bent Pyramid, which likely started off too steep and was adjusted half way to a smaller angle (see Fig. 117). Both turned out to be unstable and were abandoned. Sneferu’s final pyramid was the Red Pyramid, which became his burial place. It is the first true pyramid and reached a height of 105 meters (see Fig. 118).

Fig. 116 – The Meidum Pyramid (26th century BC) (Kurohito, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Fig. 117 – The Bent Pyramid (26th century BC) (Lienyuan Lee, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Sneferu’s son, Khufu (26th century BC), was the greatest pyramid builder. He built the Great Pyramid of Giza, which contains an astonishing 2.5 million blocks averaging 2.5 tons each and reaches a height of 147 meters. Inside the pyramid are various passageways. Especially impressive is the Grand Gallery, with its tall corbelled ceiling, which leads to the King’s Chamber, the burial place of Khufu, which is located 43 meters above the ground. The room is not decorated and only contains Khufu’s sarcophagus. Both the walls of this chamber and the sarcophagus are made of granite blocks from Aswan, some weighing about 80 tons.

Fig. 118 – The Red Pyramid (26th century BC) (Olaf Tausch, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Fig. 119 – The corbel-vaulted ceiling of the main burial chamber of the Red Pyramid (26th century BC) (Jorge Láscar, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Fig. 120 – The three pyramids at Giza. The largest pyramid is the Great Pyramid of Giza (26th century BC) (Robster1983, CC0 1.0)

Fig. 121 – Grand Gallery at Giza (26th century BC) (Keith Adler, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Fig. 122 – The King’s Chamber at Giza (26th century BC) (John Bodsworth)

On the outside, Khufu’s pyramid was once covered with smooth polished white limestone, which made the pyramid visible from a great distance. It also used to be topped by a pyramid-shaped capstone, which was already lost in antiquity. Some later capstones are known to have been covered with silver or gold, but it is not known whether this was also the case for the Great Pyramid of Giza.

And now the mystery of how the stones were lifted upward. Various pyramids show evidence of earthen ramps. Obviously, these ramps had to be quite long to reach high up the pyramid. Modern experiments have shown that a 2.5-ton block can be pulled upward along such a ramp. 2.5 tons, however, is far removed from the heavy 80-ton blocks above the King’s Chamber. Khufu’s Pyramid truly is an astonishing work.

The second largest pyramid on the Giza plateau is the tomb of Khafre (26th century BC), which has the famous Sphinx of Giza in front, which was carved from a huge rock. The third pyramid of Giza was built for Menkaure (26th century BC). After his reign, the era of great pyramid building was over.

In all, more than 100 pyramids were built in Egypt, all of them on the west side of the Nile, the side of the setting sun, which was the direction the soul was believed to go in its journey to the underworld.

Egyptian astronomy

Compared to their Mesopotamian neighbors,

the Egyptians made few original discoveries in the field of astronomy. However,

some curious findings concerning the Great Pyramid of Giza are worth

mentioning. First of all, the sides of the pyramid align with the four

directions to within a tenth of a degree. Also, the king’s chamber inside the

pyramid is pierced by two angled shafts (see Fig. 125). At first, ![]()

![]() these were assumed to be ventilation

shafts, yet it was later discovered that the south shaft pointed to the belt of

the constellation of Orion at the time the pyramid was built and the north

shaft to what was then the polar star. In ancient Egypt, Orion was associated

with Osiris. The polar stars were called the Indestructibles, since they

never set. In both cases, the intention might have been to guide the soul of

the dead pharaoh to his place in the afterlife. Interestingly, the king’s

chamber was also positioned off-center so that the shafts exit the pyramid at

about the same height.

these were assumed to be ventilation

shafts, yet it was later discovered that the south shaft pointed to the belt of

the constellation of Orion at the time the pyramid was built and the north

shaft to what was then the polar star. In ancient Egypt, Orion was associated

with Osiris. The polar stars were called the Indestructibles, since they

never set. In both cases, the intention might have been to guide the soul of

the dead pharaoh to his place in the afterlife. Interestingly, the king’s

chamber was also positioned off-center so that the shafts exit the pyramid at

about the same height.

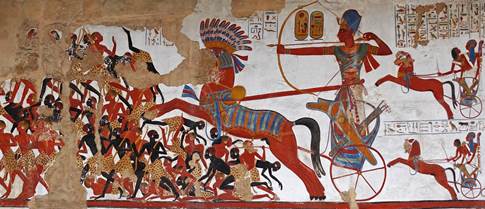

Fig. 125 – Cross-section of the Great Pyramid at Giza with two shafts pointing to Orion and the polar star (S. P. Dinkgreve, worldhistorybook.com)

The tomb of Tutankhamun

The Old Kingdom collapsed at the end of the 6th dynasty, initiating the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC). Lamentations from the later Middle Kingdom reveal that the collapse was caused by an invasion of foreigners and was interpreted as a collapse of Maat, the divine order that had kept Egypt secure for many centuries. Egypt was reunited under Montuhotep II (21st century BC), the first pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom, but fell into disarray once more four centuries later, starting the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1677–1550 BC). This time, we know the perpetrators. Egypt was invaded by a Semitic tribe known as the Hyksos, who introduced Egypt to the wheel and the war chariot. Around 1550 BC, Egypt chased the enemy out, starting the 18th dynasty under Ahmose I, which began the glory days of Egypt—the New Kingdom.

The third pharaoh of the New Kingdom, Tuthmosis I, was the first pharaoh to construct a tomb in the Valley of the Kings. These tombs were hidden underground and consisted of a long shaft leading down to elaborate burial chambers, all cut directly into limestone. The purpose of going underground was likely to make the tombs harder to find for graverobbers.

Tuthmosis I was succeeded by Tuthmosis II, who married his half-sister Hatshepsut (c. 1507–1458 BC). When Tuthmosis II died, she took power as a regent, as the successor Tuthmosis III was still underage. Later she even assumed the position of pharaoh and portrayed herself with masculine traits, including a false beard which was commonly worn by pharaohs. Later rulers clearly saw her reign as a mistake. After her death, her name was removed from her temples and later king lists skipped her name.

In the Tomb of Senenmut, possibly a lover of Hatshepsut, we find a ceiling decorated with an astronomical design (see Fig. 124). In the top half of the image, we see various planets, the star Sirius, and the constellation Orion, all symbolized as gods floating in boats. In the lower half, we see 12 circles, representing the twelve months. Each circle is cut into 24 parts, representing the 24 hours of the day, an Egyptian invention.

Fig. 126 – In front: the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari (15th century BC). In the back: the remains of the temple of Montuhotep II (21th century BC) (Ian Lloyd, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Fig. 127 – Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their children under the rays of the sun god Aten (c. 1330 BC) (Neoclassicism Enthusiast, CC BY-SA 4.0; Egyptian Museum of Berlin)

Another remarkable pharaoh of the New Kingdom was Amenhotep IV (reigned c. 1353–1336 BC), who was married to the beautiful Nefertiti. While Egypt usually stuck with tradition (personified as Maat), Amenhotep was about to turn everything upside down. He changed his name to Akhenaten in honor of the god Aten—the sun disk. He insisted that Aten was the only god, making him the first monotheist. He even closed temples dedicated to the other gods and seized their treasuries. He also claimed to have the exclusive right to worship Aten, while the rest of the population was allowed to worship only Akhenaten himself. Art during his reign, called Amarna art, showed remarkable originality, unheard of in the otherwise very conservative tradition of Egyptian art. Where in the past, pharaohs had depicted themselves as muscular and powerful, Akhenaten showed himself with a thin neck and arms, a fat belly, and an elongated face. We also see more intimate portrayals of family, such as in Fig. 127, where we see Akhenaten with his wife and children.

After his death, Akhenaten’s reforms were reversed, attempts were made to remove his name from history, and his temple at Karnak was dismantled.

Fig. 128 – Bust of Nefertiti (c. 1345 BC) (Philip Pikart, CC BY-SA 3.0; Neues Museum, Berlin)

Akhenaten was succeeded by his son Tutankhaten (c. 1341–1323 BC), who after the death of his father changed his name to Tutankhamun. The boy was only eight years old at the time and ruled for only ten years. Like his father, his name would not appear on later king lists. Howard Carter (1874–1939) famously discovered his intact tomb in 1922 in the Valley of the Kings. It is the only intact tomb of a pharaoh ever discovered. In his book, Carter vividly described his first peek into the tomb:

With trembling hands I made a tiny breach in the upper left-hand corner. Darkness and blank space, as far as an iron testing-rod could reach, showed that whatever lay beyond was empty, and not filled like the passage we had just cleared. Candle tests were applied as a precaution against possible foul gases, and then, widening the hole a little, I inserted the candle and peered in, Lord Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn and Callender standing anxiously beside me to hear the verdict. At first I could see nothing, the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold—everywhere the glint of gold [38]

Perhaps because of his early death, Tutankhamun’s tomb was smaller than usual and the walls were less extensively decorated, leaving archeologists to wonder how splendid the tombs of longer-reigning pharaohs must have looked. The four rooms of Tutankhamun’s tomb were densely packed with funerary objects and personal possessions, including chariots, two life-size statues of Tut, a throne depicting Tut and his wife, models of boats, swords, shields, bows, toys, and much more. One box contained two miniature coffins which included mummies of Tut’s stillborn daughters. A large shrine contained canopic jars, which contained Tut’s organs, which were removed before mummification.

Fig. 129 – The golden mask of Tutankhamun (14th century BC) (Harry Burton, 1925)

The burial chamber was almost completely filled with a gilded wooden shrine, which enclosed three nested inner shrines. Within them was placed a stone sarcophagus containing three further nested coffins (see Fig. 130). The outer two coffins were made of gilded wood inlaid with glass and semiprecious stones, while the innermost coffin was composed of 110 kilograms of solid gold. Within the innermost coffins lay Tutankhamun’s mummified body, with his head encased in his famous golden mask (see Fig. 129).

Fig. 130 – The nested shrines and coffins of Tutankhamun (14th century BC) (combination of Je-str, CC BY-SA 2, & own work)

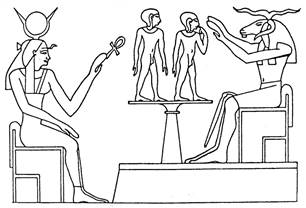

Fig. 131 – Redrawing of a relief on a monument of Amenhotep III, showing the ram god Khnum creating a human and his ka double on a pottery wheel, while the goddess Hathor gives the “ankh,” the symbol for life (14th century BC) (S. Brandon, 1969)

Mummies

This is a good moment to discuss mummification. Egyptian mummies go way back, at least to about 3600 BC, a few hundred years before the First Dynasty. At the time, bodies were deliberately mummified using linen wrappings and embalming oils. Eventually, it was discovered that natron could be used as a drying agent and an antibiotic, which stopped the decay of the body almost entirely. We first see this applied to preserve internal organs dating to about 2600 BC. It became customary to remove the stomach, the intestines, the lungs, and the liver before mummification. These organs were then placed in so-called canopic jars. The brain was also removed (by hooks through the nose) but then discarded. At the time, the importance of the brain as the seat of the mind was not yet recognized. This function was given to the heart, which was left inside the body, covered with natron.

So what was the purpose of mummification? Egyptians believed that each living person had a life force, named ka, that would live on after death but stayed close to the body and needed an intact body to survive. Therefore, the body had to be protected from decay. The ka also needed to be sustained with offerings of food and drinks. In some tombs, we also find a ka statue in which the ka could reside. Besides a ka, each person also had a ghost, named ba, which could travel to the underworld (the Duat) after death, where it was judged by the guardians of the underworld.

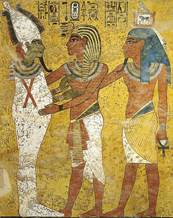

Fig. 132 – Tutankhamun and his ka embracing Osiris (14th century BC) (Solomon Witts)

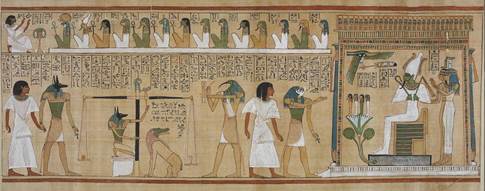

More about what the Egyptians believed happened to the soul after death can be found in the Book of the Dead (c. 1550 BC), which like the Pyramid Texts is a collection of spells to guide the soul of the pharaoh to the underworld. Two spells deal with the Weighing of the Heart. In the underworld, the heart of a deceased person was weighed on a pair of scales against an ostrich feather, which was associated with the goddess Maat, the goddess of justice. In the Papyrus of Hunefer, from 1275 BC (see Fig. 133), the jackal-headed god Anubis is weighing the heart, while the ibis-headed god Thoth, the scribe of the gods, records the result. In case the heart equaled exactly the weight of the feather, the person was allowed to pass into the afterlife, the heavenly Aaru, a field of reeds where the soul could live for eternity. If not, he was eaten by Ammit, a hybrid of a crocodile, a lion, and a hippopotamus.

Bronze Age globalization and collapse

During the 15th and 14th century BC, Egypt greatly intensified its connection with surrounding civilizations—including the Minoan civilization (Crete), the Mycenaean civilization (mainland Greece), the Hittites (Turkey), the Mesopotamians, the Canaanites (Israel), and more. Long-distance trade became so common and states became so dependent on one another that historians speak of an early form of globalization—the first truly international period in history. Direct evidence for this international outlook can be found in various Egyptian tombs. For instance, in Fig. 134, we see on the left various Greek vases and to the right a procession of foreigners, headed in the upper strip by princes of Keftiu (Crete), Hatti (the Hittites), and Tunip (probably Syria). In the lower register, only the label of the prince of Qadesh (also Syria) is readable.

Another great example of early globalization is the Uluburun ship, which sank on the coast of Turkey around 1300 BC. It is the wealthiest and most complete Bronze Age ship ever found, containing goods from seven different civilizations. There were logs from Nubia, blue glass from Mesopotamia, storage jars and a bronze statue of a deity from Canaan, scarabs from Egypt (including a solid gold scarab bearing the name Nefertiti), swords and daggers from Italy and Greece, tin and lapis lazuli probably from Afghanistan, and even a stone mace from the Balkans. Judging from personal possessions of the sailors, at least two Mycenaeans were on board of what seems to have been a Canaanite ship. [39]

![]() Fig. 134 – Redrawing of a wall painting from

the tomb of Menkheperreseneb showing Greek vases and princes from various

surrounding countries (15th century BC) The lower image is a

continuation of the upper image (Davies & Davies, 1933)

Fig. 134 – Redrawing of a wall painting from

the tomb of Menkheperreseneb showing Greek vases and princes from various

surrounding countries (15th century BC) The lower image is a

continuation of the upper image (Davies & Davies, 1933)

Fig. 135 – Wall painting from the tomb of vizier Rekhmire showing a procession of Cretans (upper panel), Nubians (middle panel), and Syrians (lower panel) bringing goods. The Cretans bring vases, the Nubians bring animals, such as leopards, giraffe, and cattle, and the Syrians bring chariots, horses, a bear, and a small elephant (c. 1400 BC)

In the 12th century this international system of trade fell apart, causing mass displacements of people and the destruction of many cities and even civilizations. The reasons for this so-called Bronze Age Collapse are still debated. It might have been a combination of natural disasters and invasions, which caused a disruption in the supply lines of the international trading system, after which everything fell apart.

Fig. 137 – Temple of Abu Simbel (12th century BC) (Olaf Tausch, CC SA-BY 3.0)

Egyptian science

Finally, a word about Egyptian inventions. In Egypt we have found the earliest catapults, drawbridges, siege towers, paved roads, sails, toothpastes, tampons (made of papyrus), sundials, water clocks, hand fans, protractors, and more. Even everyday objects like tables, chairs, and chests make their first appearance in Egypt.

The first evidence of papyrus, made from the papyrus plant, appeared around the time of Khufu (26th century BC). Papyrus is made by peeling the plant into layers, which are then dried and pressed into long sheets, that are rolled into scrolls. The oldest papyrus text found thus far is the Diary of Merer, which lists the daily activities of an official and his crew. Hieroglyphs themselves existed earlier. They were carved in stone at least as far back as 3200-3000 BC. They were deciphered only in 1822 after the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, on which the same text was written in both Egyptian and Greek.

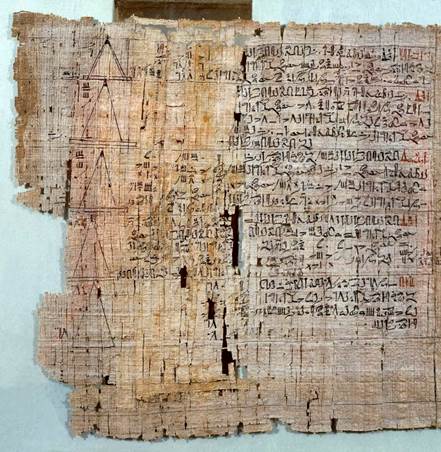

Fig. 138 – A part of the five-meter-long Rhind Papyrus (c. 1550 BC) (British Museum)

Occasionally, the Egyptians also used parchment to write on, which is made of dried animal skin. The first mention of it dates back all the way to about 2,500 BC. However, parchment became widely used much later, in the Greek city of Pergamon (Turkey) around the 3rd century BC, from which the word “parchment” later evolved.

The Egyptians were also great mathematicians, although much of their work is lost, since papyrus is very fragile, especially compared to Mesopotamian clay tablets. We do know they used a base ten numeral system, as we do today, but without place-value notation, making large numbers difficult to write down. They also recognized fractions and there was also a symbol for “plus” and “minus” (two legs pointing either forward or backward).

In the five-meter-long Rhind Papyrus, from the 2nd millennium BC, we find a list of practical math problems, likely meant to instruct students. One problem asks how to divide loaves of bread among a number of people. Some exercises also deal with pyramids, asking students to calculate their slope (seket).

Medicine in Egypt was also remarkable, already during the Old Kingdom. Physicians were quite numerous and were educated in schools known as the House of Life, which also acted as a center of knowledge. Some doctors were also specialized, for instance in surgery, childbirth, pharmacology, or in specific parts of the body. In the Edwin Smith Papyrus, we read of surgical techniques, including making splints, reconnecting bones, and stitching. The text also gives some details on how brain injuries can affect the lower limbs and provides a method for birth control (using ingredients from the acacia tree combined with honey, which has proven spermicidal effects). The Berlin Text even offers a simple pregnancy test, based on the fact that wheat does not germinate in the urine of non-pregnant women. In the Ebers Papyrus, we are given various remedies, which include the use of aloe vera for skin conditions, turmeric to close open wounds, onion to increase the production of urine, garlic as a laxative, fenugreek to calm the stomach, honey as an antibiotic, and so on. [40]