Judaism originated among Semitic tribes in Canaan, in modern-day Israel. The main historical source for the development of Judaism is the Tanakh, which came to be known as the Old Testament in the Christian tradition. The Tanakh is a document of immense importance for the understanding of the coming into consciousness of humanity, as it contains writing spread out over more than a thousand years, from before 1200 BC to the 2nd century BC. We see God transform from a tribal god who walked among men and spoke to men “face to face” to a more distance and abstract God, who often stayed completely silent, leaving his followers in doubt.

A number of stories from the Tanakh are clearly inspired by Mesopotamian myths, but the Jews gave these stories a new moral dimension. In Mesopotamia, the gods had created mankind as slaves to toil the fields. In contrast, the Jewish God showed concern for humanity. He even made a covenant with his people, in which he vowed to be on their side as long as they followed his laws. Among many other things, these laws commanded the Jews to help the poor and the needy, and even foreigners were to be treated well.

These laws of God were deemed more important than the rulings of kings, and, as a result, various prophets felt compelled to openly criticize rulers that had gone astray.

The J, E, and P source

Archeological evidence of the early history of Judaism is very scarce. Our primary source is the Old Testament itself, which is a complicated mix of fact and fiction, with many parts written and rewritten centuries after the events they purport to describe. Historians have spent much time studying the evolution of the Hebrew language to find out in what order the passages of the Bible were written. Roughly, the Hebrew of the Bible can be categorized into Archaic Hebrew (11th-10th centuries BC), Classical Hebrew (9th-6th centuries BC), and Late Hebrew (5th century BC and later) [48]. Genesis, the first book of the Bible, contains Hebrew from all three periods, but mostly stems from the Classical period (only one verse, The Blessing of Jacob, was originally written in Archaic Hebrew, and then edited somewhat).

According to the so-called Documentary Hypothesis, the Classical Hebrew in Genesis can be further subdivided into three sources, known as the Yahwist (J), the Elohist (E), and the later Priestly (P) source. One piece of evidence for these three sources is a number of doublet stories in the Bible, which are roughly similar, but also include stark contradictions. To name an example, there are two accounts of Moses hitting a large rock with his staff to obtain water. In one case, water comes out without problem (Exodus 18). In the other case, God asks Moses to speak to the rock, but he instead hits it with his staff, after which God is so offended he does not let him enter the promised land (Numbers 20). The two greatest examples of doublets are the two creation stories given in Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 and the story of Noah’s flood in Genesis 6-8, which we will discuss shortly.

Besides being doublets, these stories are also linguistically different. Especially P uses completely different words and phrases, making it easily distinguishable from the rest of the text. As the name of the source suggests, it was written by priests, the Aaronid priests of Jerusalem to be precise, who claimed to be descendants of Aaron, the brother of Moses. As expected from the priesthood, this source places an enormous emphasis on laws and rituals. P also gives Aaron a much greater role. Where J says “and Yahweh said unto Moses,” P turns this into “unto Moses and unto Aaron.” In JE, it was the staff of Moses with which miracles were performed, while in P, it became Aaron’s staff, which likely confused you if you’ve ever read the text. Most importantly, in P, Aaron is the first to perform a sacrifice, after he is consecrated as the first High Priest. This is remarkable, as JE mentions earlier sacrifices by Cain, Abel, Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and others. This change was likely part of a project by the Aaronid priests to centralize religion around them. In their view, only the descendants of Aaron could perform sacrifices, making them the only mediators between humanity and the divine. P also skipped stories in which characters are visited by angels or experience visionary dreams, as these would also give the general public access to the divine. Even the word “prophet” is only mentioned once in P, referring to Aaron. [49]

J and E generally do have the same style, and as a result the identification of these sources has been more controversial. Their style is so alike that they must be either based on each other or on a common source. There, is, however, one big difference used to distinguish J and E. J consistently uses the word “Yahweh” for God, while E consistently uses the word “Elohim”, until God reveals himself as “Yahweh” to Moses.

Dating these sources was a hard puzzle, since Genesis contains very few references to historical people or events of known date. Yet there are a handful of clues. For instance, the J source named Babylon the great world-city and called Calah (Nimrod) the great city of the Assyrian Empire, which narrows this source down to the 9th-8th centuries. Also, J refers to the dispersion of the tribes Simeon and Levi, but not to the dispersion of the other tribes of Israel, which occurred in 722 BC. It also mentions Edom’s independence, which occurred during the reign of Jehoram, which started c. 848 BC. So, J was likely written between c. 848 BC and 722 BC. Source E refers to conflicts between Israel and Aram, which also confines it to the 9th-8th centuries.

In the P source, the Mesopotamian city Ur is called “Ur of the Chaldeans,” but the Chaldeans only gained political power in the 7th-6th centuries. Most scholars believe P was written in the 6th century BC, after the Temple of Jerusalem was destroyed and the Jews were deported to Babylon. This would explain, for example, why P makes no mention of the Temple and why P places the origin of Jewish rituals before the monarchy, since the monarchy no longer existed. But others note that both Jeremiah and Ezekiel quote from P, while Ezekiel was deported to Babylon and Jeremiah fled to Egypt, suggesting that the text must have existed before the deportation.

Fig. 194 – Stele of the god Baal with a thunderbolt (c. 14th century BC) (Jastrow; Louvre)

The origins of the Hebrew God

The Bible places the origin of the Jews in Ur in Mesopotamia, yet archeological remains and linguistic and religious comparisons from 1200-1000 BC confirm that Israel formed within Canaanite culture. The overlap between the material culture and language of Israel and the other Canaanite tribes is so large at this point in time that they are often indistinguishable. Yet, Israel did break itself off from the other Canaanites at least by 1208 BC, because both Canaan and Israel are mentioned as separate entities on a stele by pharaoh Merneptah. We read on this stele: “Plundered is the Canaan” and “Israel is laid waste.” Interestingly, the hieroglyphs used to denote Canaan on this stele signifies that it is a land, while the hieroglyph for Israel contains an image of a man and a woman, which denotes that it is a people or an ethnic group.

Originally, each of the tribes of Canaan seems to have had its own patron god from the Canaanite pantheon, such as El, Baal, and Asherah. The original God of the tribe of Israel seems to have been El. In fact, most scholars believe that “Israel” originally meant “El rules.” The name Yahweh seems to have been a later adoption. This might explain why in both P and E, God is called El early on in the narrative, until he reveals himself as Yahweh to Moses, which might be an ancient memory of the adoption of the god Yahweh by the Israelites. Moreover, seventeen characters in Genesis have names compounded with “El” (such as Bethel), while there are no names that contain “Yahweh” (interestingly, there is one name compounded with “Baal,” namely Benjamin’s son Ashbel).

In later books of the Bible, names compounded with “YHWH” become common, although the name seems to have been pronounced as Yahu or Yaho at the time. We have Yirmeyahu (Jeremiah), Yesayahu (Isaiah), and Yehonatan (Jonathan).

Place names from the 2nd millennium BC also show an absence of Yahweh. We do have cities containing the name of the god Anat (Anatoth), Baal (Baal-perazim), Dagon (Beth-Dagon), El (Beth-El), Yarihu (Jericho), Shalimu (Jeruselam, from Jerushalim), and Shamash (Beth-Shemesh). Many of these gods were part of the Canaanite pantheon.

We know about this pantheon mainly from a number of texts on clay tablets from the 13th-12th centuries BC found in the city of Ugarit in northern Syria. Among these texts we have found the Baal Cycle, which describes a myth about the thunder god Baal, literally meaning “lord.” One of the great achievements attributed to Baal is his victory over a sea god named Yam, literally meaning “sea,” and his serpentine servants Tannin and Lotan. Interestingly, this myth seems to have been adopted by the followers of Yahweh. In the Bible, we read:

It is you who broke the Sea [yam] with your strength, you smashed the head of the Dragon [tannin] on the waters. It is you who shattered the heads of Leviathan [possibly Lotan]. [50]

Fig. 195 – A painted jar showing Yahweh and Asherah (8th century BC) (Wikimedia)

In the Ugaritic texts, we also read that the highest god El was married to the goddess Asherah and that their children included the gods of the morning star, the evening star, the sun, and the moon. In some cases, Baal was also mentioned as one of their children. Words on potsherds from the eighth century BC read “Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah,” suggesting the goddess was married to Yahweh instead.

Interestingly, the line even came with a drawing (see Fig. 195), possibly showing the divine couple. Similarly, we have an inscription from around the same time, which states:

Uriyahou the rich has written it: May Uriyahou be blessed by Yhwh, who has saved him from his enemies through his Asherah.

Traces of these past beliefs are also found in the Bible. Firstly, the name “Elohim” has a plural ending and can mean both “god” and “gods,” depending on the form of the associated verb. For instance, we read in Genesis I:

Then Elohim said, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness.”

There are also several passages in which El is described as the leader of a council of gods. For instance, we read:

For who in the skies above can compare with the Lord? Who is like the Lord among the heavenly beings? In the council of the holy ones, God (El) is greatly feared; he is more awesome than all who surround him. [50]

And:

God (Elohim) presides in the great assembly; he renders judgment among the gods. [50]

In the Bible, we also read that El, here a god of the entire earth, divided up the nations of the world among his sons, giving Israel to his son Yahweh:

When the Most High (Elyon) allotted the nations for inheritance, when He divided up humanity, He fixed the boundaries for peoples, according to the number of divine sons: For Yahweh’s portion is his people, Jacob his own inheritance.

If you look up this verse in most English translations of the Bible, you read that God gave the nations to “the children of Israel” instead of his “divine sons.” However, the 3rd century BC Greek translation of the Bible and also the Dead Sea Scrolls give the translation just given. The verse was later likely altered to avoid the implication of polytheism.

In time, however, it came to be believed that El and Yahweh were two names for the same God. And El became a generic word for God, no longer a proper name.

Genesis

The first book of the Old Testament is called the Book of Genesis (meaning “origins”). It starts with two accounts of the creation of the world and the first human beings. Surprisingly, these two accounts give a contradictory story. The first account, Genesis I, was written by source P late in the Classical period, around the sixth century BC. As we shall see, this account of creation is very formal and methodical.

It speaks of a universal, omnipotent, and transcendent God named “El” (or Elohim) who uses his words to create order from chaos. We famously read:

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters.

And God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light. God saw that the light was good, and he separated the light from the darkness. God called the light “day,” and the darkness he called “night.” And there was evening, and there was morning—the first day.

And God said, “Let there be a vault between the waters to separate water from water.” So God made the vault and separated the water under the vault from the water above it. And it was so. God called the vault “sky.” And there was evening, and there was morning—the second day.

And God said, “Let the water under the sky be gathered to one place, and let dry ground appear.” And it was so. God called the dry ground “land,” and the gathered waters he called “seas.” And God saw that it was good.

Then, God said, “Let the land produce vegetation: seed-bearing plants and trees on the land that bear fruit with seed in it, according to their various kinds.” And it was so. The land produced vegetation: plants bearing seed according to their kinds and trees bearing fruit with seed in it according to their kinds. And God saw that it was good. And there was evening, and there was morning—the third day.

And God said, “Let there be lights in the vault of the sky to separate the day from the night, and let them serve as signs to mark sacred times, and days and years, and let them be lights in the vault of the sky to give light on the earth.” And it was so. God made two great lights—the greater light to govern the day and the lesser light to govern the night. He also made the stars. God set them in the vault of the sky to give light on the earth, to govern the day and the night, and to separate light from darkness. And God saw that it was good. And there was evening, and there was morning—the fourth day.

And God said, “Let the water teem with living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the vault of the sky.” So God created the great creatures of the sea and every living thing with which the water teems and that moves about in it, according to their kinds, and every winged bird according to its kind. And God saw that it was good. God blessed them and said, “Be fruitful and increase in number and fill the water in the seas, and let the birds increase on the earth.” And there was evening, and there was morning—the fifth day.

And God said, “Let the land produce living creatures according to their kinds: the livestock, the creatures that move along the ground, and the wild animals, each according to its kind.” And it was so. God made the wild animals according to their kinds, the livestock according to their kinds, and all the creatures that move along the ground according to their kinds. And God saw that it was good.

Then, God said, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.”

So, God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.

God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.”

Then, God said, “I give you every seed-bearing plant on the face of the whole earth and every tree that has fruit with seed in it. They will be yours for food. And to all the beasts of the earth and all the birds in the sky and all the creatures that move along the ground—everything that has the breath of life in it — I give every green plant for food.” And it was so.

God saw all that he had made, and it was very good. And there was evening, and there was morning—the sixth day. Thus, the heavens and the earth were completed in all their vast array.

By the seventh day, God had finished the work he had been doing; so on the seventh day he rested from all his work. Then, God blessed the seventh day and made it holy because on it he rested from all the work of creating that he had done. [50]

Notice also that while the Mesopotamian gods created humanity as the slaves of the gods, Genesis states that humans are made in the image of God, making them respectable in their own right and even close to divine.

The second account, Genesis II, was written earlier by J between 900 and 750 BC, and uses “Yahweh” as the name of God. Here, we find ourselves in a particular place, the Garden of Eden (meaning “pleasure”). Instead of an abstract and transcendent God who spoke from the Heavens, we are now told of an anthropomorphic God who “walked” in the Garden of Eden “in the cool of the day.” This version of God is more reminiscent of the spirits from tribal mythology. The purpose of creation no longer was to methodically create order from chaos, but to create workers to work the ground of his garden (“to till it and keep it”)—a clear Mesopotamian theme. God then fashioned a human being from mud, another Mesopotamian theme:

Then the Lord God formed a man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being.

Instead of creating male and female simultaneously, as in Genesis I, his first creation is a man named Adam (meaning “man”). We read:

Then the Lord God formed man (ha-adam) from the dust from the ground (adamah).

The similarities between “ha-adam” and “adamah” accentuate the relationship between Adam and the soil.

Time and again, we find that God in the J source is more emotionally involved with humanity. Here, we read God felt compassion for his creation, stating: “it is not good for the man to be alone.” To solve this problem, he first created the animals and allowed Adam to name them, but Adam found no “partner fit for him.” God then created a woman from his “side” or “rib.”

Then God warned:

You must not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, for when you eat from it you will certainly die.

But not long after, the woman was tempted by a snake to eat from the tree. At first, she resisted, but then the snake responded that God had not been telling the truth:

You will not die, for God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like the gods, knowing good and evil.

This convinced her to take a bite, and then “she also gave some to her husband and he ate.” As a result of eating the fruit, the couple began to feel shame, experiencing a loss of innocence. We read:

Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made loincloths for themselves. They heard the sound of God walking in the garden at the time of the evening breeze, and the man and his wife hid themselves from the presence of God among the trees of the garden. But God called to the man, and said to him, “Where are you?” He said, “I heard the sound of you in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked; and I hid myself.” He said, “Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten from the tree of which I commanded you not to eat?” The man said, “The woman whom you gave to be with me, she gave me fruit from the tree, and I ate.” Then, God said to the woman, “What is this that you have done?” The woman said, “The serpent tricked me, and I ate.’’

God then cursed all three of them. To the woman, he said:

I will greatly increase your pangs in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children, yet your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.

To Adam, he said:

Because you have listened to the voice of your wife, and have eaten of the tree about which I commanded you, “You shall not eat of it,” cursed is the ground because of you; in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you; and you shall eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your face, you shall eat bread until you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; you are dust, and to dust you shall return.

Adam then named the woman Eve, in Hebrew “Havva”, which is related to the word “hayya,” meaning “life-bearer.” We read:

Adam named his wife Eve, because she would become the mother of all the living.

In Aramaic, the word Eve is related to the word “snake” (“hivya”). This might be the origin of the later tradition, which equated the woman and the snake for their shared blame of introducing sin into the world (see Fig. 196).

As the snake had predicted, Adam and Eve became “like the gods, knowing good and evil.” Fearing they might eat from another tree—the tree of life—God commanded them to leave Eden:

And the Lord God said, “The man has become like one of us, knowing good and evil. He must not be allowed to reach out his hand and take also from the tree of life and eat, and live forever.” So the Lord God banished him from the Garden of Eden to work the ground from which he had been taken. After he drove the man out, he placed on the east side of the Garden of Eden cherubim and a flaming sword flashing back and forth to guard the way to the tree of life.

Fig. 196 – The Fall of Men by Michelangelo (c. 1510). Notice the snake is depicted as a woman (Sistine Chapel)

Noah and the Great Flood

Adam and Eve had two sons, named Cain and Abel. These brothers continued the downward spiral of mankind. Cain, the firstborn, was a farmer, and his brother Abel was a shepherd. The brothers made sacrifices to God, each from their own produce, but God favored Abel’s sacrifice over Cain’s. We read that Abel sacrificed “of the firstlings of his flock and of their fat portions,” while Cain just brought “an offering of the fruit of the ground.” Out of jealousy, Cain killed Abel, committing the first murder in history. As a result, God condemned Cain to a life of wandering.

The misdeeds of humanity continued, and at some point, God saw no other option but to destroy his creation with a Great Flood. The story mirrors the Flood Myth from the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh quite closely, but there are some crucial differences as well. Whereas the Mesopotamian gods wanted to wipe out humanity because they made too much noise, here, God is concerned with the moral behavior of mankind. God could no longer accept the evil in the world and therefore decided to eliminate it.

Like the creation myth in Genesis I and II, this story is also told twice, again with crucial differences. But here, both sources are cut up and interlaced, forming one somewhat coherent story, although with various doublets and contradictions. Crucially, if these sources are read apart, we get two complete versions of the story, each with its own typical vocabulary and theological emphasis. And, again, one source consistently calls god “Yahweh,” and the other “Elohim.”

Again, source J takes the emotional route, stating: “Yahweh saw how great was the evil of man on the earth. [He] regretted that he had made man on earth and his heart was deeply troubled.” He concluded: “I shall wipe out man (adam) […] from the face of the soil (adamah).” P does not speak of regret, but again takes the more objective cosmic route focused on maintaining order. He simply observes the state of the earth and concludes that creation has to be reversed, almost as a matter of sheer cause and effect. [51]

Now the earth was ruined before God, for the earth was filled with violence. […] The end of all flesh has come before me […]. I shall soon ruin them on the earth.

Before sending the flood, however, he instructed a man named Noah to prepare an ark. Noah was described as “a righteous man, blameless in his generation,” who “walked with God.” In J, he was instructed to bring his family and also seven pairs of all clean animals and one pair of all unclean animals. These extra clean animals were required by J, as Noah would sacrifice these animals right after leaving the ark. In P, however, Noah performs no sacrifice and therefore simply takes two of every animal onto the ark.

Then it starts to rain. In P, the flood is described as a cosmic catastrophe. We read that “the fountains of the great deep were broken up and the windows of the heavens were opened.” In J, it simply rains, but God does personally close Noah’s ark, in line with his more personal nature. In J, the flood lasts 370 days and in P it takes 40 days and 40 nights.

Eventually, Noah sent out a bird to see if the water had retreated—a dove in J and a raven in P (and a dove, a swallow, and a raven in The Epic of Gilgamesh). After a while, the bird returned with an olive leaf, suggesting it had found land.

Fig. 197 –Noah sending a dove from the Ark (12th century) (Saint Mark’s Basilica, Venice)

When the water finally receded, the ark stranded on a mountain top where Noah (according to J) sacrificed animals to God. In the Mesopotamian epic, the gods “gathered like flies over the sacrifice” as they couldn’t survive without them. This made the god Enlil regret his decision to wipe out mankind. In the Biblical version, God too “smelled the pleasing aroma” of the sacrifice, leading him to show mercy for humanity despite its flaws. We read:

The Lord smelled the pleasing aroma [of the sacrifice] and said in his heart: “Never again will I curse the ground because of humans, even though every inclination of the human heart is evil from childhood. And never again will I destroy all living creatures, as I have done.”

Then, in P alone, we read God established a covenant with mankind, promising never to wipe out humanity again. God then created the rainbow as the sign of this covenant.

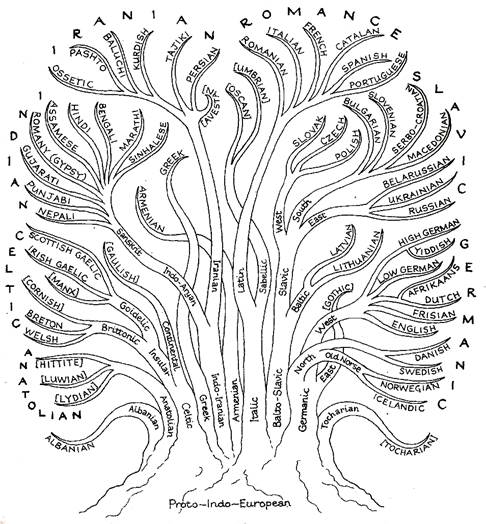

In the next chapter of the Bible, we read that humans once again tried to defy God, this time by building a tower tall enough to reach heaven, called the Tower of Babel. This tower is likely a parody of the Babylonian ziggurats that were believed to connect heaven and earth. To prevent the people from succeeding, God changed the languages of the builders so that they could no longer understand each other and, therefore, could not finish the project. He then scattered the builders around the world, giving rise to all the different nations with their own distinct languages.

Fig. 198 – The tower of Babel by Pieter Breugel the Elder (c. 1563). (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Abraham

Then the Bible introduces us to the patriarch Abraham and his descendants. The internal genealogy of the Bible, which includes figures living unrealistically long, dates Abraham back to 2100 BC. The story that has come down to us, however, can never be this old, as evidenced by some chronological errors. For instance, the text mentions the Philistines and the Arameans, who did not arrive in Canaan until about the 12th century BC. The camel is also mentioned, which wasn’t domesticated until the 11th century and was in common use much later. As mentioned before, the story was likely written down somewhere in the 9th of 8th century BC, yet some verses do suggest there must have been earlier versions of the story, evidenced by references to archaic practices that became objectionable in later times. For instance, Abraham claims that Sarah is both his sister and his wife, which is forbidden in later parts of the Bible. God also doesn’t tell Abraham to burn the idols of his ancestral gods, which would later be mandated by the Ten Commandments.

According to P, Abraham originally came from the Sumerian city of Ur, then travelled along the Fertile Crescent to Haran, located in the Semitic region known as Aram (in modern-day Turkey), until he finally settled in Canaan. J and E do not mention Ur, but only Haran. As a result, some scholars have hypothesized that Haran was Abraham’s actual birthplace. This would explain why the direct forefathers of Abraham (Serug, Nahor, and Terah) were named after villages around Haran. Abraham’s brother is even called Haran. It might also explain the name “Hebrew,” likely meaning “across [a river],” as Haran is located on the opposite side of the Euphrates. [48]

In any case, Abraham, at that point still known as Abram, was called by God to settle in Canaan, which God had designated his promised land. There, he led a nomadic lifestyle, living in tents and herding livestock. God gave his word that Abram would become a progenitor of nations, but after years and years of trying, his wife did not get pregnant. Instead, Abraham chose to impregnate a slave girl named Hagar. This decision made Sarah so jealous that she made Hagar’s life miserable, causing her to flee into the desert. Hagar’s son was named Ishmael, who (so the story tells us) became the ancestor of the Arabs. After thirteen years, when Abram was ninety-nine, God declared that Sarah would finally bear him a legitimate heir. When Abraham heard these words, he laughed and said to himself:

Will a son be born to a man a hundred years old? Will Sarah bear a child at the age of ninety.

But God insisted and even claimed:

No longer will you be called Abram; your name will be Abraham [meaning “father of a multitude”], for I have made you a father of many nations.

Abraham then received instructions for a new covenant between God and his people, with circumcision as its sign.

It turned out God was right. Sarah did become pregnant and gave birth to a son, Isaac. A few years later, God commanded Abraham to offer Isaac as a sacrifice. Ever obedient to God, Abraham had his son carry the wood for his own sacrificial altar. When Isaac asked why they hadn’t brought an animal for the sacrifice, Abraham replied, “God will provide himself a lamb for a burnt offering.” Just as Abraham was about to sacrifice his son, he was interrupted by an angel. Then a ram appeared to be sacrificed in place of his son. Later rabbis explained the encounter as God’s rejection of human sacrifice, but the text does not make this explicit, and Abraham is praised by God for his willingness to sacrifice his son.

On another occasion, God told Abraham he was about to destroy the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah because of the sinful behavior of their inhabitants. Abraham negotiated with God to spare the cities if he could find “at least ten righteous men” there. God agreed, but Abraham could not find these men. God then sent two angels to rescue Abraham’s nephew Lot before destroying the city. Lot invited the angels into his home, baked them bread, and offered them shelter for the night. After supper, however, the men of the city gathered around Lot's house hoping to have sex with the angels. To appease the crowd, Lot offered them his virgin daughters to do with as they wished. The following morning, the angels urged Lot and his family to leave, after which God rained sulfur and fire on the cities. Lot’s wife glanced back at the divine spectacle, which turned her into a pillar of salt.

Jacob and Joseph

The most notable event in the life of Jacob, son of Isaac, was his encounter with a mysterious being with whom he wrestled:

So Jacob was left alone, and a man wrestled with him till daybreak. When the man saw that he could not overpower him, he touched the socket of Jacob’s hip so that his hip was wrenched as he wrestled with the man. Then the man said, “Let me go, for it is daybreak.” But Jacob replied, “I will not let you go unless you bless me.” The man asked him, “What is your name?” “Jacob,” he answered. Then the man said, “Your name will no longer be Jacob, but Israel, because you have struggled with God and with humans and have overcome.” […] Then he blessed him there. So Jacob called the place Peniel, saying, “It is because I saw God face to face, and yet my life was spared.”

Notice, once more, that this God, who wrestles and negotiates with a human, reminds us more of the spirits from tribal mythology than of the abstract God of Genesis I (and as expected, the text is identified not as P, but as a combination of J and E).

Jacob had twelve sons, who became the progenitors of the twelve tribes of Israel. He preferred his son Joseph, which made his brothers very jealous. To get rid of him, they sold Joseph to Arabic merchants who were on their way to Egypt. Once in Egypt, Joseph worked his way up to become the servant of Potiphar, the captain of the pharaoh’s guard. When Potiphar’s wife attempted to seduce him, Joseph refused. Angered by this, she made a false accusation of rape, for which he was convicted. In prison, Joseph met the pharaoh’s chief cupbearer and his chief baker. They told him about their dreams, which Joseph interpreted to mean that the chief cupbearer would be reinstated, while the chief baker would be hanged. His interpretation turned out correct. Two years later, the pharaoh dreamt of seven lean cows that devoured seven fat cows and of seven withered ears of grain that devoured seven fat ears. When the pharaoh’s advisers failed to interpret these dreams, the cupbearer remembered Joseph. Joseph was summoned to the court, and he told the pharaoh that the dreams predicted the coming of seven years of abundance followed by seven years of famine. To avoid catastrophe, Joseph advised the pharaoh to store surplus grain. When the prediction came true, Joseph was made vizier to the pharaoh.

Moses and the Exodus

According to the Bible, the presence of Joseph in the court of the pharaoh caused many Israelites to leave Canaan and settle in Egypt. Genesis ends with the death of Joseph. According to Egyptian tradition, he was mummified, as can be read in the last line:

So Joseph died at the age of a hundred and ten. And after they embalmed him, he was placed in a coffin in Egypt.

Four hundred years later, a pharaoh came to power who became suspicious of the Jews, fearing they would eventually conspire against him. As a result, he turned them into slaves and ordered all newborn Hebrew boys to be killed. One child was spared this fate. He was hidden by his mother, who placed him in a basket by the riverbank. The baby was found by the pharaoh’s daughter, who adopted the child and named him Moses (an Egyptian name). This story seems to have been inspired by a legend associated with King Sargon of Akkad, who was also said to have been placed in a reed basket as a baby to avoid execution by an evil king.

When Moses reached adulthood, he killed an Egyptian who was beating a Jew. To escape the death penalty, he fled and eventually ended up on Mount Horeb. Here, God spoke to him from within a burning bush:

God called to him from within the bush, “Moses! Moses!” And Moses said, “Here I am.” “Do not come any closer,” God said. “Take off your sandals, for the place where you are standing is holy ground.” Then, he said, “I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob.” At this, Moses hid his face, because he was afraid to look at God.

The Lord said, “I have indeed seen the misery of my people in Egypt. I have heard them crying out because of their slave drivers, and I am concerned about their suffering. So I have come down to rescue them from the hand of the Egyptians […] I have seen the way the Egyptians are oppressing them. So now, go. I am sending you to Pharaoh to bring my people the Israelites out of Egypt.”

For a few moments, God miraculously transformed Moses’s staff into a snake. Then Moses asked God for his name. Here, he reveals his name Yahweh, which, the text claims,

“If I come to the people of Israel and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name? what shall I say to them?’ In other words, ‘Which god are you?’ Then what shall I tell them?” God said to Moses, “I am who I am.” And he said, “Say this to the people of Israel: ‘I am has sent me to you.’” God also said to Moses, “Say this to the people of Israel: ‘Yahweh, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you.’ This is my name forever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations.”

The phrase “I am who I am” is linguistically related to Yahweh (yhwh) since “h-y-h” (or “h-w-h”) is Hebrew for “to be.” In this way, the Bible tried to explain Yahweh’s name at a time when its original meaning had been forgotten.

A little later in the chapter, God added that he had not revealed this name to his earlier followers:

I am Yahweh. I appeared to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, as God Almighty (El-Shaddai), but by my name Yahweh, I did not make myself known to them.

Fig. 199 – Moses before the burning bush taking off his shoes and covering his face, from the Golden Haggadah (1320 AD) (The British Library)

Fig. 200 – The plague of frogs, from the Golden Haggadah (1320 AD) (The British Library)

After meeting with God, Moses and his brother Aaron went to the pharaoh to ask for the release of the Jews from slavery. This time, God turned Aaron’s staff into a snake. The court magicians of the pharaoh copied the trick, only to have their snakes swallowed by Aaron’s. Yet the pharaoh refused to release the slaves, and as a result, God subjected Egypt to ten plagues. The first plague caused all the waters in Egypt to turn into blood, the second plague caused countless frogs to climb from the Nile, and so on. About the last plague, we read:

This is what the Lord says: “About midnight I will go throughout Egypt. Every firstborn son in Egypt will die, from the firstborn son of Pharaoh, who sits on the throne, to the firstborn of the slave girl, who is at her hand mill, and all the firstborn of the cattle as well. There will be loud wailing throughout Egypt—worse than there has ever been or ever will be again.”

God then commanded Moses to inform all the Jews to smear lamb blood above their doors, which prevented the “destroyer” from coming into their houses.

Curiously, after each plague, the pharaoh was inclined to free the slaves, but then God helped him to “harden his heart” and persist. Only after all ten plagues did the pharaoh allow the Jews to leave Egypt, which is known as the Exodus (meaning “going out”). But when Moses led the Israelites to the border of Egypt, God hardened the pharaoh’s heart once more, which caused him to send his army after them. When the Israelites were trapped between the “Reed Sea”[2] and the army, Moses stretched out his hand with his staff and parted the sea with God’s power, allowing the Israelites to cross.

The Exodus strongly shaped Jewish morality. It gave the Jews a strong reminder to keep faith in God and to follow his commandments:

Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm.

It also reminded them not to oppress others:

You shall not wrong a stranger nor oppress him, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt. [25]

The historicity of the Exodus

According to the chronology of the Bible itself, the Hebrews should have been in Egypt from about the 19th to the 15th century BC, yet during this period there is no evidence of the existence of a people known as “Hebrews” or “Israelites,” not even in Canaan itself. There did live some Semites in Egypt at this early stage. For instance, the Hyksos, a Semitic tribe, conquered and ruled Egypt in the 17th-16th century. We have also found a tomb of a man named Aper-El (servant of El), clearly a Semitic name, who served as vizier to Pharoah Amenhotep III and Akhenaten during the 14th century. The earliest known mention of Israel finally occurred on the Merneptah Stele from 1207 BC, written in Egypt during the reign of Pharaoh Merneptah, son of Ramses II.

If we are to take the presence of Hebrews in Egypt seriously at all, the most likely pharaoh of the Exodus is the same Ramses II. According to the Bible, the Hebrew slaves were forced to build the cities Pithom and Rameses, which actually exist and were indeed constructed during his reign.

Overall, however, the consensus is that the presence of large groups of Hebrews in Egypt and their subsequent escape are firmly in the realm of fiction.

Fig. 201 – Moses crossing the Red Sea, from the Golden Haggadah (1320 AD) (The British Library)

The Ten Commandments

Once escaped from Egypt, Moses led the Israelites to Mount Sinai. He climbed the mountain by himself, where he met with God, who handed him stone tablets “inscribed by the finger of God.” On these tablets, God had written the Ten Commandments. When Moses came down from the mountain, his skin gave off rays of light as a result of having talked with God. As a result, his people reacted in fear. When Moses realized this, he covered himself with a veil until the light had worn off. The Ten Commandments read:

I am the Lord, your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery. You shall have no other gods before me [1]. You shall not make for yourself an idol [2], whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I the Lord your God am a jealous God, punishing children for the iniquity of parents, to the third and the fourth generation of those who reject me, but showing steadfast love to the thousandth generation of those who love me and keep my commandments. You shall not make wrongful use of the name of the Lord your God [3], for the Lord will not acquit anyone who misuses his name.

Remember the sabbath day, and keep it holy [4]. Six days you shall labor and do all your work. But the seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God; you shall not do any work—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female servant [slave], your livestock, or the alien resident in your towns. For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but rested the seventh day; therefore, the Lord blessed the sabbath day and consecrated it.

Honor your father and your mother [5], so that your days may be long in the land that the Lord your God is giving you. You shall not murder [6]. You shall not commit adultery [7]. You shall not steal [8]. You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor [9]. You shall not covet your neighbor’s house; you shall not covet your neighbor’s wife, or male or female servant [slave], or ox, or donkey, or anything that belongs to your neighbor.[10]

Then Moses discovered that some people had begun to worship a statue of a golden calf in his absence, disobeying God’s commandment not to worship idols. Out of anger, Moses broke the tablets, melted the golden calf, ground it into powder, and fed it to the idolaters. He then went back to God and asked for new tablets. God also gave Moses instructions to build the Ark of the Covenant, which was a gold-covered wooden chest in which the two tablets were placed. Wherever the Israelites camped, the Ark was placed in a separate room in a sacred tent, which was called the tabernacle. The tabernacle was considered the dwelling of God on earth.

Mosaic Law

The Ten Commandments are just a small part of a large body of rules that can be found in the Old Testament, together named the Mosaic Laws. Through these laws, Moses entered into another covenant with God. So long as the Israelites obeyed these laws, they would be God’s chosen people. We read:

For you are a people holy to the Lord your God. The Lord your God has chosen you out of all the peoples on the face of the earth to be his people, his treasured possession.

Since it was God who set the rules, Moses presented himself not as a king of his people, but as God’s prophet. This turned out to be a clever move since it pressured later leaders to conform to these objective laws instead of just doing as they pleased.

Some laws now seem horribly backward, but some have stood the test of time. Take, for instance, the laws that call for tolerance and care for others. Perhaps the most famous example is:

Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against anyone among your people, but love your neighbor as yourself. I am the Lord.

This famous golden rule even extends to foreigners:

The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt. I am the Lord your God.

We also find many passages calling for charity for the poor. For instance, we read:

If any of your fellow Israelites become poor and are unable to support themselves among you, help them […] so they can continue to live among you. Do not take interest or any profit from them, but fear your God, so that they may continue to live among you.

Unlike any other religion at the time, Judaism stressed that to help the poor is to honor God:

Whoever oppresses the poor shows contempt for their Maker, but whoever is kind to the needy honors God.

However, despite their own history of enslavement, the Old Testament does not condemn slavery. For instance, we read:

Anyone who beats their male or female slave with a rod must be punished if the slave dies as a direct result, but they are not to be punished if the slave recovers after a day or two, since the slave is their property.

Laws about sexual conduct are also notoriously backward. For instance, homosexuality is punishable by death. We read:

If a man has sexual relations with a man as one does with a woman, both of them have done what is detestable. They are to be put to death.

The death penalty is also reserved for idolatry, taking God’s name in vain, violation of the Sabbath, and so on. If a woman has sex before marriage, the Old Testament recommends:

She shall be brought to the door of her father’s house and there the men of her town shall stone her to death. She has done an outrageous thing in Israel by being promiscuous while still in her father’s house. You must purge evil from among you.

The return to the promised land

Taking the Ark of the Covenant with him, Moses led the Israelites to the borders of Canaan. He then sent twelve spies into the land, who reported back that their former land was inhabited by giants. This news frightened the Israelites, who had no faith that God would protect them if they entered their homeland. Instead, they proposed to return to Egypt. As a punishment for their distrust, God made the Israelites wander the wilderness for forty years until all who had doubted had died. At some point along this journey, even Moses failed to trust God. God had told him to command a rock to yield water for the Israelites, but Moses instead struck the rock twice with his staff. As a result, God punished him by not letting him enter the promised land. On the banks of the Jordan River, in sight of Israel, Moses assembled the tribes and passed his authority to Joshua, after which he died at the age of 120.

We then learn that “since then, no prophet has risen in Israel like Moses, whom the Lord knew face to face.” This verse refers to a number of encounters Moses had with God in a tent he set up in the desert. In this tent “the Lord would speak to Moses face to face, as one speaks to a friend.” These are the only times when Moses had such a direct encounter with God. In other instances, he instead appeared indirectly as a burning bush, a cloud, or a huge pillar of fire. With Moses gone, the time had ended when man could meet God as though he was a tribal spirit. Here, we are starting to see a process that will unfold over centuries of Jewish history—namely, the profaning of history. Slowly over the many pages of the Old Testament, we will see the mythological psyche of humanity transform into a more secular mind, where God gets a more distant and indirect relationship with his creation. The Old Testament documents our psychological evolution over the period of a millennium, making it a unique document in world history. [29]

Back in Canaan, Joshua reclaimed the promised land through holy war. After defeating their enemies, the Israelites divided the land among the twelve tribes. At this stage in the book, we also find the laws for holy war. When victorious, the Israelites should offer peace in exchange for forced labor. If the enemy did not surrender, all adult males were to be killed, but not the women and children. However, God sometimes allowed for exceptions to his own rule:

In the cities of the nations the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance, do not leave alive anything that breathes. Completely destroy them—the Hittites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites, and Jebusites—as the Lord your God has commanded you. Otherwise, they will teach you to follow all the detestable things they do in worshiping their gods, and you will sin against the Lord your God.

The judges

Back in the promised land, the so-called judges became the dominant political leaders of Israel. The judges were war leaders who, in times of crises, united the tribes of Israel to fend off threats from neighboring peoples. The first judge was Othniel, who responded to a threat from Mesopotamia. Othniel’s story followed a pattern that was repeated by several judges. The story starts at a moment when the people of Israel “did what was evil.” As a result, God allowed his people to be conquered by a foreign power. When the people understood their wrongdoings and cried out to the Lord, God responded by sending a judge. In this case, it was Othniel. Othniel received the divine spirit, waged war, and prevailed. And then the pattern starts all over again:

“Again the Israelites did evil in the eyes of the Lord.”

Surprisingly, the judges felt no need to stay in power after the crisis was over, let alone start a royal line. The fifth judge, Gideon, made this point explicitly. After freeing the people of Israel, he was asked by the people to become their king and establish a dynasty, but Gideon refused, saying:

I will not rule over you, nor will my son rule over you. The Lord will rule over you.

Yet Gideon was also the first judge who doubted God. He complained about God’s inaction and asked God for miracles to prove he was on his side (another sign of the secularization of history). When an angel appeared, Gideon said to him:

If the Lord is with us, why has all this happened to us? Where are all his wonders that our ancestors told us about when they said, “Did not the Lord bring us up out of Egypt?” But now the Lord has abandoned us and given us into the hands of Midian.

With subsequent judges, the breakdown of the pattern continued. More and more, the judges failed to receive the spirit of the Lord. Jephthah was not even commissioned by God but by town leaders, without any divine involvement. Finally, when Israel was again in complete disarray, the people began to yearn for a stable monarch.

The fourth judge deserves a special mention, as she was the only female. Deborah was a prophetess at a time when Israel came under attack by King Jabin of Hazor. She was commanded by God to instruct General Barak to resist the foreign army, which led to victory. The leading general of the opposing army was finally killed by another woman, Jael, who rammed a tent peg through his skull. The story is presented both as prose and poetry. The poetic version, called The Song of Deborah, is written in Archaic Hebrew, likely dating to the 12th century BC.

King David

Then the word of the Lord, “which was rare in those days,” came to Samuel when he was “lying down in the temple, where the ark of God was.” Samuel became a successful judge, but when he got old, he made his sons judges over Israel, and they turned out to be immoral leaders. This again made the people yearn for a stable king, but Samuel feared a king would undermine Yahweh’s kingship. He also reminded the people that a king would conscript their sons into the army and impose a tenth of their flock in taxes. Finally, God decided for him:

I will send you a man from the land of Benjamin. Anoint him ruler over my people Israel; he will deliver them from the hand of the Philistines. I have looked on my people, for their cry has reached me.

This person was Saul. Saul became the first king of Israel, yet he seems to have been only slightly more powerful than his predecessors. He still had no army of his own, he ruled not from a capital city but from his own estate, and there was no system of taxes.

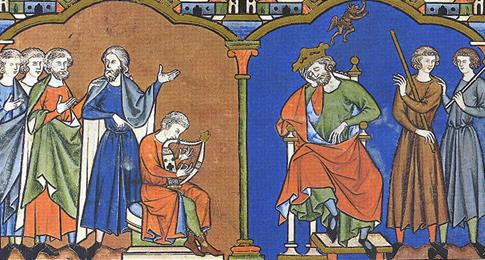

Saul’s kingship did not go as planned. He broke the rules of holy war by not sacrificing the spoils of a raid and by sparing the king of his enemy. As a result, God caused an “evil spirit” to overtake him. He became tormented by the spirit and could only be comforted by his harp player David (see Fig. 202).

Fig. 202 – Saul troubled by an evil spirit, while David soothes him with his harp. From the Maciejowski Bible (c. 1250 AD) (The Morgan Library)

Fig. 203 – David bringing the Ark of the Covenant into Jerusalem. From the Maciejowski Bible (c. 1250 AD) (The Morgan Library)

When another war broke out between Israel and the Philistines, the giant Goliath challenged the Israelites to send out one warrior to face him in single combat. David declared that he could defeat Goliath and killed the giant with his sling (although, in another verse, the victory is attributed to the soldier Elhanan). Because of his victory, Saul allowed David to command his army, but his popularity soon caused Saul to fear his place on the throne. As a result, Saul made plans to kill David, but he was warned just in time by Saul’s son Jonathan and managed to escape. Saul then searched the land for David. He finally entered a cave where he was hiding. This gave David an opportunity to kill him, but he instead decided to only cut off the corner of his robe. When leaving the cave, he presented the piece to Saul as proof of his good intentions. As a result, Saul recognized him as his successor.

When Saul was killed in battle, David was anointed king. Once in charge, he conquered Jerusalem, presumably by sending his soldiers up a water shaft. He made it his capital city and used it as a stronghold from which to defeat the Philistines. He also brought the Ark of the Covenant to the city. The prophet Nathan then revealed that God had made an eternal covenant with the house of David, stating:

Your throne shall be established forever.

Chronologically, David must have lived around 1000 BC. Although the existence of the Kingdom of David seems probable, historical evidence is meager. Some archeologists believe we have found the remains of his palace in Jerusalem, called the Large Stone Structure, which does date to the 10th century BC, but it can’t be definitively linked to David or his successors. We have also found a potsherd which reads “the men and the officers have established a king,” which might refer to the coronation of Saul, although his name isn’t mentioned. The only real clue is the Tel Dan stele, likely erected by an Aramaic king from about 900 BC. It mentions “B Y T D W D,” which is generally interpreted to mean “House of David.” The text also mentions the death of the Israelite king Jehoram (9th century BC), the son of King Ahab, two characters also mentioned in the Bible. Assyrian stelae known as the Kurkh monoliths also mention King Ahab, placing him firmly within history.

Let’s now continue David’s story. Just like his predecessor Saul, he too went astray. He spied on a married woman called Bathsheba, who was bathing on a nearby rooftop. He then summoned her over and impregnated her. To get her husband out of the way, he sent him to the front lines, where he died. Obviously, “the thing David had done displeased the Lord.” Nathan prophesied that David would be punished, claiming “the sword shall never depart from your house.” God said:

Before your very eyes I will take your wives and give them to one who is close to you, and he will sleep with your wives in broad daylight.

The person mentioned turned out to be David’s son Absalom, who revolted against his father, took his concubines, and slept with them before the people of Israel. When David acknowledged he had sinned, Nathan told him his son would die as punishment. In fulfillment of Nathan’s words, Absalom was caught by his long hair in the branches of a tree, where he was killed by the commander of the army, contrary to David’s order.

Solomon

After David’s death, the throne passed on to his son Solomon. When God appeared to him in a dream, he asked him if there was anything he wanted. Solomon asked for wisdom, which pleased the Lord as it was not a self-serving request. As a result, God answered his prayer.

Solomon did much to solidify the throne. He ordered the construction of a palace and also built the Temple of God, in which he placed the Ark of the Covenant. In many ways, Solomon became a typical Near Eastern king. Whereas David financed most of his activities with war booty, Solomon relied on taxation and forced labor. The money coming in filled up the treasury and allowed him to import many luxury items. Like his Mesopotamian counterparts, he placed himself at the center of religion, claiming a special relationship with God. For instance, he is described as “seated at the right hand of God” and is called “the firstborn of God.” This relationship was emphasized by him living in the sacred city Jerusalem, on the holy mount Zion, next to the Temple of God.

Fig. 204 – Solomon and Queen of Sheba worshipping an idol, from The Flowers of Virtue (1411 AD)

Fig. 205 – The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III. The Jewish king Jehu bows before Shalmaneser III (c. 825 BC) (GFDL, CC BY-SA 3.0; British Museum)

But even Solomon went astray. He built up too much capital, in disagreement with Mosaic Law, and disregarded the command to “not acquire many wives for himself” (it is said he had “three hundred wives and seven hundred concubines”). His wives, who often came from foreign lands, “turned his heart after other gods.” He even built temples to worship them. This angered God, and, as a result, “the Lord punished Solomon by removing ten of the twelve Tribes of Israel from the Israelites.” We read:

Since this is your attitude and you have not kept my covenant and my decrees, which I commanded you, I will most certainly tear the kingdom away from you and will give it to one of your subordinates. Nevertheless, for the sake of David your father, I will not do it during your lifetime. I will tear it out of the hand of your son.

When Solomon’s son Rehoboam succeeded him, ten of the tribes of Israel refused to accept him as king. As a result, these ten tribes split off, forming the northern kingdom of Israel under Jeroboam. Rehoboam only retained the much smaller southern kingdom of Judah. The two kingdoms would remain separated for two hundred years. Not long after, under the rulership of King Jehu, Israel became a vassal state of Assyria, as confirmed by a relief on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III (9th century BC), showing the Assyrian king receiving “the tribute of Jehu” (see Fig. 205).

The prophets

After the breakup of the kingdom, a number of prophets felt called by God to criticize the wrongdoings of both Israel and its rulers. While the kings had been trying to monopolize the relationship with God, the prophets claimed to have their own channel to the divine. They often packaged their messages from God in fantastical, esoteric, and often incomprehensible metaphors, visions, and dreams.

Their message was usually negative, warning that Israel would be destroyed if the people continued to sin against God. These harsh messages often made the prophets disliked, placing them outside of mainstream society and sometimes in direct conflict with rulers (some kings even executed prophets). Yet, despite their negativity, they also stressed that God was willing to forgive those who truly repented.

Elijah

The prophet Elijah was a miracle worker and the leader of his own prophet school in the northern kingdom of Israel during the 9th century BC. He lived during the reign of the Jewish King Ahab, who married the Phoenician princess Jezebel. Influenced by his wife, Ahab adopted the deities Asherah and Baal, which incurred the anger of Elijah. In response, Elijah challenged 450 prophets of Baal to have their god set aflame a sacrifice by lightning strike, which shouldn’t be too much of a problem for a thunder god. The priests of Baal prayed all day, but with no success. When Elijah ridiculed their efforts, the priests stepped up their game and started cutting themselves, adding their own blood to the sacrifice, which is strictly forbidden by Mosaic Law. But still, they had no success. Then it was Elijah’s turn. He asked God to accept the sacrifice, after which fire fell from the sky consuming both the sacrifice and the stone altar itself. Elijah then put the priests of Baal to death and cursed the house of Ahab.

In hindsight, it is easy to read monotheism in this story, but this does not seem to be the case. Elijah did not deny the existence of Baal, but thought of him as inferior to Yahweh. Following the Ten Commandments, Elijah did not deny the other gods, but only placed Yahweh above them.

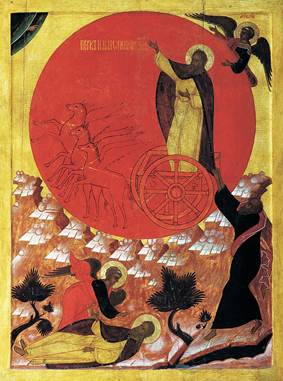

Fig. 206 – Elijah ascending to heaven in a fiery chariot (c. 1570) (Russia) (cirota.ru)

Angered that Elijah had killed her prophets, Jezebel threatened to kill him. As a result, Elijah fled to Mount Horeb, where he took shelter in a cave. Here, God spoke to him:

What are you doing here, Elijah?

Elijah did not give a direct answer. Instead, he bitterly complained about the unfaithfulness of the Israelites and claimed he was “the only one left.” God then told him to leave the cave and “stand before the Lord.” When outside, a terrible wind passed, but Elijah could not find God in the wind. A great earthquake shook the mountain, but God was not in the earthquake either. Then a fire passed, but God was also not in the fire. Then a “still small voice” came to Elijah and asked him once more:

What are you doing here, Elijah?

Elijah again evaded the question, showing that he did not understand the importance of the divine revelation he had just witnessed. Baal was a nature god, but Yahweh was not. God, instead, had appeared to him in a more subtle form.

In fulfillment of Elijah’s curse, Ahab was finally killed on the battlefield and Jezebel was thrown out of a window.

At the end of his life, Elijah was carried to heaven in a fiery chariot. When he departed, the prophet Malachi predicted his return “before the coming of the great and terrible day of the Lord.”

Amos and Hosea

In the 8th century BC, the prophets Amos and Hosea strongly criticized Israel in esoteric poetic verses. They claimed that by forsaking justice and faith, the Jews had violated the Covenant Law and would soon feel the wrath of God. In one monologue, Amos opened with a series of pronouncements against Israel’s neighbors. But then he turned to Israel and Judah and condemned them for the same transgressions. He even concluded that Israel’s crimes were more heinous because of their special relationship with Yahweh. He concluded:

For three sins of Judah, even for four, I will not relent. Because they have rejected the law of the Lord and have not kept his decrees, because they have been led astray by false gods, the gods their ancestors followed, I will send fire on Judah that will consume the fortresses of Jerusalem.

For three sins of Israel, even for four, I will not relent. They sell the innocent for silver, and the needy for a pair of sandals. They trample on the heads of the poor as on the dust of the ground and deny justice to the oppressed.

He then continued with five dramatic symbolic visions prophesying the destruction of Israel. We read:

Then the Lord said to me: “The end is ripe for my people Israel; I will spare them no longer.”

Amos claimed that Yahweh was even willing to take the side of the Assyrians if Israel would continue to break the covenant. We read:

For the Lord God Almighty declares, “I will stir up a nation against you, Israel, that will oppress you all the way from Lebo Hamath to the valley of the Arabah.”

The prophet Hosea also prophesied Israel’s doom, believing that its destruction was imminent:

Put the trumpet to your lips [meaning: sound the alarm]! An eagle is over the house of the Lord because the people have broken my covenant and rebelled against my law. Israel cries out to me, “Our God, we acknowledge you!” But Israel has rejected what is good; [so] an enemy will pursue him.

According to Hosea, God did all he could to maintain a special relationship with the Israelites, but they kept rejecting him. God was like a rejected parent:

When Israel was a child, I loved him, and out of Egypt, I called my son. But the more they were called, the more they went from me. They sacrificed to the Baals and burned incense to [idols]. [Yet,] it was I who taught Ephraim [a son of Joseph] to walk, taking them by the arms; but they did not realize it was I who healed them. I led them with cords of compassion, with ties of love. To them I was like one who lifts a little child to the cheek, and I bent down to feed them.

As it turned out, their cause for alarm was justified. Around 730 BC, the Assyrian king Tiglathpileser III (c. 795–727 BC) attacked Israel, after which a large number of Jews were deported to various parts of the Assyrian Empire in order to reduce the threat of revolt. This would be the first of a number of deportations. The second deportation occurred in 722 BC under King Sargon II (762–705 BC), who deported about five percent of the Jewish population to various parts of his empire. In an inscription, we read that he “led away as booty 27,290 inhabitants.”

Finally, it is worth mentioning that Hosea and Amos preferred moral action over rituals, breaking with an important Neolithic mindset. In Hosea, God speaks the following revolutionary words:

I desire mercy, not sacrifice, and acknowledgment of God rather than burnt offerings.

In Amos, we read:

I hate, I despise your religious festivals; your assemblies are a stench to me […] Away with the noise of your songs! I will not listen to the music of your harps. But let justice roll on like waters and righteousness like an [ever-flowing] stream.

Strangely, Hosea also felt directed by God to marry a promiscuous woman of ill-repute so that their marriage could symbolize the broken relationship between God and Israel. Just as his wife violated the obligations of marriage, so too did the people of Israel worship other gods and break the commandments of the covenant.

Isaiah

The prophet Isaiah is tough to pin down in history, as references to him cover three distinct time periods. The early Isaiah (chapters 1-23 and 28-39) tried to stop King Hezekiah (c. 700 BC) from forming an alliance with the upcoming Babylonians against Assyria. He prophesied that the “days are coming when all that is in your house, […] shall be carried to Babylon; nothing shall be left, says the Lord.” The king refused to listen and proceeded with the plan, after which the Assyrians quickly defeated the Babylonians and then set out to attack Judah. In the early stages of the attack, the Jewish city Lachish was captured and its inhabitants were deported (see Fig. 207).

When the Assyrians pressed on, surrounding Jerusalem, King Hezekiah offered to pay the Assyrians for their withdrawal. Isaiah, once more, disagreed, advising the king to do nothing and trust God. He prophesied: “By the way that [the Assyrian leader] came, by the same he shall return; he shall not come into this city.” Again, Isaiah was right. “The angel of the Lord struck down [the Assyrians]”, killing many, after which the enemy retreated. It has been suggested that perhaps a disease had broken out in the enemy camp.

Jeremiah and the Babylonian exile

Around 586 BC, King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon conquered Judah and Israel, destroyed Jerusalem and its temple, and forced another deportation, known as the Babylonian exile.

The prophet Jeremiah was active in Judah during this time. To him, the fall of Judah meant that the covenant had fallen. With the destruction of the city of God and its temple, including the Ark of the Covenant, the covenant with God could only be maintained in a more abstract sense. This is precisely what Jeremiah suggested—he predicted the coming of a new covenant, one no longer established by literature, but by the heart. We read:

“This is the covenant I will make with the people of Israel after that time,” declares the Lord. “I will put my law in their minds and write it on their hearts. I will be their God, and they will be my people. No longer will they teach their neighbor, or say to one another, ‘Know the Lord,’ because they will all know me, from the least of them to the greatest,’ declares the Lord.”

Yet, the people of Judah were not willing to listen and Jeremiah was condemned by both priests and kings. He was almost sentenced to death and was put in prison until he was released by the Babylonians.

Ezekiel

The prophet Ezekiel (6th century BC) lived among the Babylonian exiles. He found himself in a community that was confident that God would rescue them, but Ezekiel insisted they were incorrect, as they were not yet deserving of redemption. Yet there was also some good news. Ezekiel was convinced that God was still in control. In fact, it was God who had caused the deportation, which the Jews had brought upon themselves because of their bad behavior. Redemption was possible, Ezekiel claimed, but only if the Jews would repent.

Ezekiel was also known for his incomprehensible prophecies. In his chariot vision, he described a chariot made of heavenly beings with many faces and angels shaped like “wheels inside of a wheel.” In his valley of the dry bones vision, he saw himself standing in a valley full of dry human bones. The bones connected into skeletons and then became covered with flesh and skin.

Ezekiel also broke with an important tradition. The Jewish community had traditionally believed that sin could be inherited from father to son. Instead, Ezekiel stressed individual responsibility:

The child will not share the guilt of the parent, nor will the parent share the guilt of the child. The righteousness of the righteous will be credited to them, and the wickedness of the wicked will be charged against them.

Isaiah II

The prophet Isaiah, in his second and third incarnation (chapters 40-55 and even later 56-66), wrote during the Babylonian exile, when Jerusalem was already destroyed. His message is one of consolation. He claimed that although the Babylonians had been victorious, it was not Marduk but Yahweh who controlled history. The exile had been predicted by God, making it likely that his prediction of the restoration of Israel would also come true—and he was right. In 539 BC, the Persian king Cyrus took over Babylon, granted their subjects religious freedom, and even allowed the Jews to return home. This is confirmed by the Cyrus Cylinder, dated to 528 BC. King Cyrus also helped finance the rebuilding of the Jewish temple, starting the Second Temple Period (515 BC–70 AD). According to Isaiah, Yahweh had appointed the Persian king to defeat Babylon and to return the exiles in a new Exodus. Cyrus, in Isaiah’s view, became Yahweh’s anointed (‘messiah’) in his plan for the salvation of Israel.

In Isaiah, we also find the first clear statement of monotheism. God told him:

I am the first and I am the last; apart from me there is no God.

This was the first time the existence of other gods was outright denied.

The end of the age of the prophets

The Jews finally returned home, but this did not end their problems, as the land had turned to ruin. In the Book of Isaiah, we read:

Your sacred cities have become a wasteland; even Zion is a wasteland, Jerusalem a desolation. Our holy and glorious temple, where our ancestors praised you, has been burned with fire, and all that we treasured lies in ruins.

The prophet Haggai had the same complaint. About the poor condition of the temple, he remarked:

Who of you is left who saw this house in its former glory? How does it look to you now? Does it not seem to you like nothing?

Haggai described a population that was starving. Not surprisingly, many questioned the value of serving Yahweh. Disillusioned by this letdown, the age of the prophets came to an end. After so much had been lost, what more doom could they preach? With the monarchy no longer functioning and the prophets with nothing left to say, the people turned to the priests, who kept the people together with laws and traditions.

Job

In the Book of Job (c. 6th century BC), an attempt was made to understand how an omnipotent and just God could allow unfairness to exist in the world. The story introduces Job as an ideal figure, continually engaged in pious action and blessed with wealth, sons, and daughters. The scene then shifts to heaven, where God asked Satan (literally “the accuser”) for his opinion on Job’s piety:

Have you considered my servant Job? There is no one on earth like him; he is blameless and upright, a man who fears God and shuns evil. [Fear of the sublime nature of God was considered a virtue].

Satan answered that Job was pious only because God had blessed him with a good life. To prove Satan was incorrect, God gave him permission to take away Job’s wealth and kill all of his children, but Job continued to praise God, accepting his losses with faithful resignation. We read:

Job got up and tore his robe and shaved his head. Then he fell to the ground in worship and said, “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked I will depart. The Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; may the name of the Lord be praised.” In all this, Job did not sin by charging God with wrongdoing.

God then allowed Satan to afflict his body with boils, which Job scraped with potsherds to stop the itching. Job’s wife encouraged him to curse God, but Job answered:

Shall we accept good from God, and not trouble?

Eventually, Job cracked, lamenting the day he was born:

Why did I not perish at birth, and die as I came from the womb?

Three friends tried to console him, but they could not believe that Job was innocent, since God would not cause a man such suffering if he had not sinned. They advised him to repent and seek God’s mercy. Instead, Job protested his innocence, listed the principles by which he had lived, and demanded that God answer him.

When God finally spoke from a whirlwind, he did not explain himself, nor did he apologize or defend his divine justice. Instead, he contrasted Job’s weakness with his divine wisdom and omnipotence:

Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth?

Job responded by acknowledging God’s power and his own lack of knowledge “of things beyond me which I did not know.” Having seen God with his own eyes, he declared:

My ears had heard of you, but now my eyes have seen you. Therefore I despise myself and repent in dust and ashes.

With these words, Job accepted his insignificance in the face of the almighty God. Finally, Job’s health and riches were restored and he had new children, whom he lived to see to the fourth generation.

Heaven and hell

It might surprise you that we didn’t meet the figure of Satan earlier in the chapter. Even in the Book of Job, he is by no means the demonic force that we are familiar with from the later Christian tradition. Perhaps even more surprisingly, the Old Testament doesn’t even refer to either heaven or hell. We do occasionally read about a place called Sheol, a place of darkness to which all the dead go, regardless of their moral choices in life. We have seen this type of afterlife already in the myths from Mesopotamia. In Sheol, the dead exist as shades (rephaim), entities without personality or strength. It was believed that the living could come into contact with them through magical practices, but this was forbidden by Mosaic Law. The closest to the concept of heaven is Shamayim, which was described as a place located above the firmament, where Yahweh lived in his heavenly palace, but this was not considered a destiny for humans.

In the last few centuries BC, ideas about the afterlife would drastically change in various Jewish communities, but this will be a topic for a later chapter.