The renouncers of the Upanishads set the minds of Indian intellectuals on the spiritual quest for enlightenment (samadhi) and the escape from the endless wheel of death and rebirth (samsara). In the centuries that followed, dozens of influential schools popped up, all promising their students the true teaching to reach these goals. One of these schools was Jainism, which is known for its extreme adherence to the principles of Indian philosophy and therefore serves as an insightful case to understand these principles.

The most influential school of the time was Buddhism, which advocated a more lenient approach, called the Middle Way. Despite the mythology that came to surround the life of the Buddha, his original teachings are remarkably practical and down to earth.

Jainism

According to the Jains, the universe is a colossal female being, with the earth plane at the level of her waist, seven hells beneath, and fourteen celestial levels above. Soaring above her head is an umbrella-shaped object of luminous white gold to which released souls ascend when all their karma has burned away through yoga. This cosmic being was believed to be made out of matter (a-jiva) forced into various shapes by an infinite amount of wandering souls (jiva). Each soul had already passed through an infinite number of incarnations and would likely continue to do so for millions more, becoming dust, sand, stone, precious stones, seas, lakes, snow, plants, flames, lightning, meteors, breezes, inhalations, exhalations, animals, humans, fiends in the upper hells, divine serpents, gods, spirits, suns, moons, constellations, stars, and much more.

Different from the Abrahamic God, the cosmic being was believed to operate impersonally, without any knowledge of the souls. Instead, her karmic judgments work automatically and mechanically through karma. According to the Jains, karma is a particulate substance that connects to the soul when deeds of violence are committed, making the soul heavy and dark. With good deeds, this substance disconnects again, lightening the soul. When a person dies, the jiva is released from the body. If heavy from all the karma, it will sink into the hells below. If light, it will rise to the heavens.

To rid themselves of this karmic debt, Jain disciples practiced non-violence and extraordinary gentleness towards all beings. The vow of non-violence even extended to insects and plants. Jains weren’t even allowed to break fruit from a tree but had to wait for it to fall down naturally. Grain could only be eaten before it sprouted, when it did not yet contain a jiva. Jains also had to reduce participation in the world as much as possible. They were even supposed to limit their movements, the amount of food they ate, and the number of objects they used. Only through the absolute rejection of the world could the karmic debt dry up. In one Jain text, we read:

As a large pond when its influx of water has been blocked, dries up gradually through consumption of the water and evaporation, so the karmic matter of a monk, which has been acquired through millions of births, is annihilated by austerities, provided there is no further influx. [70]

The next step was to actively burn the remaining karmic matter through yoga. Disciples were expected to create heat (tapas) within themselves to burn out the karmic matter and thus lighten the soul until it was completely clean. After death, the freed soul floats all the way up to the great luminous umbrella, where it enjoys eternal and supreme bliss. There, unreachable by any prayer and isolated from the burden of life, the jiva experiences infinite knowledge, perception, energy, and bliss. In the words of the mythologist Joseph Campbell:

The released, weightless monad is not to be reached by any prayer. It is indifferent to the cycling maelstrom far beneath. It is all-aware, though unthinking; alone yet everywhere. It is without individual character, personality, quality, or definition. It is simply perfect. [60]

The Jains recognize twenty-four saviors who managed to achieve this, the last being Mahavira (c. 6th century BC), who is believed to have lived around the time of the Buddha, or perhaps slightly earlier. It is said that Mahavira himself burned away his last karma by refusing to eat and drink and by standing still without disturbing anything until his body died and his jiva reached nirvana. The previous savior, Parshva, is said to have lived three centuries earlier, which would place him before the Upanishads, but little evidence exists to confirm this.

The ego: East and West

In its final state, the jiva was believed to be completely devoid of personal characteristics, memories, and even thoughts and actions. To Indian philosophers, this was perfection. This is in stark contrast to the Western concept of heaven, where the continuation of personality and memories after death is one of its appealing aspects.

This contrast points to an important difference between Eastern and Western philosophy. In the East, the ego is believed to distort reality, making it seem as though we are separate individuals, while, in reality, we are all one. As a result, any Jain or Buddhist reaching nirvana is believed to be identical to his predecessors. This idea is clearly reflected in Buddhist art. Images of the Buddha generally have exactly prescribed postures, gestures, and proportions. The more perfect the work, the more closely it adhered to these standards. This also meant that creating original work was rarely on the minds of Eastern philosophers and artists, since perfection was already defined in the past.

In the West, the ego isn’t treated as an illusion but is instead celebrated. Here, individuality is seen as the essence of a human being. Sure, the ego can be immature, but the solution is not to erase it altogether but to cultivate it. In the West, every individual is considered unique and free to pursue his own destiny. What is valued is not what is the same in everyone but what makes us stand out from all the rest. The idea of losing our individual character in favor of some formless divine essence is not our greatest hope but our greatest fear.

This difference also has consequences for religion. Being a distinct person, the highest spiritual achievement in the West is a strong relationship with God. In this view, man is distinct from and inferior to God. In the East, in contrast, every person is believed to carry within himself the divine source of the universe. This makes everyone and everything divine.

The story of the Buddha

The Buddha is believed to have lived in the 6th or 5th century BC. His first full biography, however, known as the Buddhacarita by Ashvaghosha, appeared only in the 2nd century AD. By that time, his life’s story had turned into legend. According to the story, a boy named Gautama grew up as a prince in a palace. He was magically born from the side of his mother Maya, had depictions of wheels on the soles of his feet, webbed fingers and toes, and since he had “nurtured his self through untold eons,” he came to the world already conscious and able to speak. Based on these miraculous events, a number of brahmins predicted the boy would become either a great world leader or an awakened seer. A prophet named Asita then heard a divine voice, telling him the second option would become reality—the boy was born for awakening.

At first, Gautama’s father, King Suddhodana, was overjoyed hearing about his son’s future success, but his joy turned to anxiety when he realized this meant his son would become a hermit and end his royal line. In an attempt to avoid this fate, Suddhodana shielded his son from all the suffering in the world, so he would see no need to turn to a religious life. Gautama came to live in beautiful chambers on the top floor of his father’s palace and was given all the delights the world had to offer to ensure he would never think of leaving. As he grew older, his father also made sure to surround him with beautiful women of pleasure:

In that palace women entertained him with soft voices and alluring gestures, with playful drunkenness and sweet laughter, with curling eyebrows and sidelong glances. Then, ensnared by women skilled in erotic arts, who were tireless in providing sexual delights, he did not come to earth from that heavenly mansion. [71]

His father also arranged for him a beautiful bride, named Yashodhara, with whom he had a son, named Rahula.

But Gautama’s curiosity could not be contained. Having heard of the beauty of nearby groves, he wanted to see them. His father granted his wish, but he staged the trip thoroughly to prevent him from seeing anything that would upset him. He was moved around in a golden chariot with four horses on a road covered with flowers, yet the gods had other plans and intervened with four sights of suffering. The first one was the appearance of an old man. We read:

“Who is that man there with the white hair, feeble hand gripping a staff, eyes lost beneath his brows, limbs bent and hanging loose? Has something happened to alter him, or is that his natural state?” “That is old age,” said the charioteer, “the ravisher of beauty, the ruin of vigor, the cause of sorrow, destroyer of delights, the bane of memories, and the enemy of the senses. In his childhood, that one too drank milk and learned to creep along the floor, came step by step to vigorous youth, and he has now, step by step, in the same way, gone on to old age.” “What! And will this evil come to me too?” “Without doubt, by the force of time,” said the charioteer. [72]

Gautama was in shock and asked to be driven home, but soon he was ready for another trip. This time, the gods sent a man afflicted by disease:

The prince said, “Yonder man, pale and thin, with swollen belly, heavily breathing, arms and shoulders hanging loose and his whole frame shaking, uttering plaintively the word ‘mother’ when he embraces there a stranger: who is that?” “My gentle lord,” said the charioteer, “that is disease.” “And is this evil peculiar to him, or are all beings alike threatened by disease?” “It is an evil common to all,’ said the charioteer. […] And a second time, the prince, trembling, desired to be driven home.

A third time, the gods made a dead man appear:

“But what is that, borne along there by four men, adorned but no longer breathing, and with a following of mourners?” The charioteer, having his pure mind overpowered by the gods, told the truth. “This, my gentle lord,” he said, “is the final end of all living beings. Whether one is low born, in the middle, or noble, in this world for all men death is certain.” Gautama responded, “How can a rational being, knowing these things, remain heedless here in the hour of calamity? Turn back our chariot, charioteer. This is no time or place for pleasure.’’

But this time, the charioteer was instructed not to return, but instead to go to a festival of women in the groves. There, the Brahmin Udayin sent a group of gorgeous women to Gautama, hoping they could keep him away from religion:

With determination [the women] set their minds on captivating the prince. […] Some of [them], under the pretense of being drunk, touched him with their firm and full breasts. […] Another, pretending that she was drunk, repeatedly let her blue dress slip down. […] Others, grasping branches of mango in full bloom, bent down to expose breasts resembling golden pots. […] One girl with full and charming breasts, her earrings shaking with her laugh, made fun of him loudly, saying: “Catch me, sir!” [71]

But their distractions no longer worked:

[Gautama] wavered not, nor rejoiced, firmly guarding his senses, and perturbed at the thought: “[…] Do these women not know that old age will one day take away their beauty? Not observing disease, they are joyous here in a world of pain. And, to judge from the way they are laughing at their play, they know nothing at all of death.”

This is not to say that Gautama rejected pleasure in and of itself, “but knowing that the world is transient, [his] heart [found] no delight in them at all.” He said: “If old age, sickness, and death, these three things were not to exist, I would also have found delight in delightful pleasures of sense.”

The fourth sight of suffering occurred when Gautama was riding his white horse across a field that had just been plowed. In the grass, he saw insects that had been killed in the process.

He grieved greatly, as if a kinsman had been killed. Seeing the men plowing the fields, their bodies discolored by the wind, the dust, the scorching rays of the sun, oxen wearied by the toil of pulling the plows, great compassion overwhelmed that great noble man.

Fig. 223 – Gautama meditating under the rose apple tree (3rd century AD) (Mark Mauno, permission)

Filled with deep sorrow, Gautama got off his horse and sat down at the foot of a rose apple tree. “Reflecting on the birth and death of all creatures,” a feeling of selfless empathy suddenly overtook him. Instinctively he positioned himself in the yoga posture and entered a trance. He became calm and felt momentarily released from any attachment to the world:

He sat down, and as he began to contemplate the origin and destruction of all creatures, he embarked upon the path of mental stillness. Achieving at once the state of mental stillness, and freedom from worries [and] sensual desire, he attained the first trance.

Then a monk appeared before him—the fourth sight. Gautama asked who he was, and the man answered:

Terrified by birth and death, desiring liberation, I became an ascetic. As a beggar, wandering without family and without hope, accepting any fare, I live now for nothing but the highest good.

After these words, the man rose up into the sky and disappeared, revealing himself to be a god. After the encounter, Gautama went to his father to tell him he wanted to become a monk, but his father tried to persuade him not to go:

O my son, keep back this thought. It is not time for you to be turning to religion. During the first period of life the mind is fickle and the practice of religion full of danger.

Gautama answered:

Father, it is not right to lay hold of a person about to escape from a house that is on fire.

Fig. 224 – Gautama escapes from the palace. Earth spirits prevent his father from waking up by catching the hoofs of his horse. (Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY 3.0; Indian Museum of Kolkata)

But his father would not let him go. Back at the palace, Gautama sat down on his golden seat, surrounded by his women playing beautiful music, but then the gods used their magic to make the women fall asleep. They dropped their instruments and fell to the floor, where they lay with their hair disheveled and their skirts and ornaments in disarray. Many of them were breathing noisily and drooling, while others lay as if dead. Gautama thought:

Such is the nature of women: impure and monstrous in the world of living beings! Deceived by dress, a man becomes infatuated by their charms.

After this experience, Gautama knew he had to escape the palace. The gods magically opened the door of the palace, and Gautama rode out with the help of his charioteer. When outside the city, Gautama looked back and roared like a lion, stating he would not return until he had “seen the farther shore of birth and death”. He also said goodbye to his charioteer. In tears, he responded:

O master! What will your poor father say, and your queen with her little son? And O Master, what is to become of me?

Gautama replied:

The meetings of all beings end inevitably in separation. My good friend, do not grieve, but depart; [To those back home] say only that I shall either return having slain old age and death, or else myself perish, having failed. […] I am not to be mourned, nor have I departed at a wrong time for the forest. There is, in fact, no wrong time for religion.

He then cut off his long hair, which he threw in the air, where heavenly beings caught it.

Then Gautama entered “the ascetic grove, with no longing for kingdom, wearing dirty clothes,” in search of monks who could teach him the path to salvation.

He entered that forest—with trees darkened by the smoke of fire oblations, a forest rendered tranquil by ascetic toil, a forest that was like the workshop of dharma, and crowded with seers who had just taken their baths, with blazing sacred fires being taken out, and its divine shrines humming with the sound of the hushed recitation of mantras. […] Then, he saw those hermits rich in austerities, with matted hair, wearing garments of bark and grass. [71]

When the ascetics saw him, they thought he was a god, as he “lit up the entire forest.” He spoke with various teachers, who all taught him different forms of asceticism. Some made offerings in a fire while singing mantras, while others plunged into the water and lived among the fish. With each teacher he found, he listened carefully to their teachings, but eventually he rejected them all. One of the most significant of these teachers was the sage Arada. He told Gautama:

Now, as to the cause of temporal existence: it is threefold, namely, ignorance, action, and desire, each leading to the other two. No one abiding in this cycle attains to the truth of things. Such wrong abiding is the prime mistake, from which derive, in series: egoism, confusion, indiscrimination [and attachment]. One imagines “This am I,” then “This is mine,” whereupon one is drawn downward to new births.

So, what was Arada’s solution? We read:

First of all, the mendicant life. The practice [...] of restraint of the senses. To be rid of all sense of body. [...] Experience the void of the body or considering the dweller in the body to be all space. [Then] abolish the sense of being a person by considering the supreme Person.

This made Gautama think, but he did not accept Arada’s teachings:

It cannot be final, for it does not teach how to get rid of the Person, the supreme Self itself. Though the self, when purified, may be termed free, yet as long as that Self remains, there is no real abandonment of egoism. [...] I hold that the only absolute attainment is in absolute abandonment.

He stood up, bowed, and moved on to find his next teacher.

Fig. 225 – Fasting Gautama (c. 200 AD) (Percy Brown; Lahore Museum)

A little later, Gautama joined a group of monks who were practicing severe fasting, until his ribs were sticking out “like a row of spindles” (see Fig. 225). According to the Majjhima Nikaya, he further added to his suffering by lying on a mattress of spikes, eating his own urine and feces, and at one point, even the gods thought he was dead. Yet, despite all his effort and all his suffering, it did not help. His body kept asking him for attention, and he still experienced lust and cravings. He then began to question the approach. How was one to attain liberation without any strength? Suddenly he recalled his first meditation at the foot of the rose apple tree. “That is the true way,” he thought. There was no need for extreme fasting. Instead, the mind should be put at rest by having just the right amount of food to satisfy the senses so that craving disappears. This path of moderation he called the Middle Way between pleasure (kama) and pain (mara). Gautama later explained in one of his sermons:

Oh, monks, these two extremes ought not to be practiced by those who have gone forth from the household life. What are these two? There is devotion to the indulgence of sense pleasures, which is low, common, the way of ordinary people, unworthy, and unprofitable; and there is devotion to self-mortification, which is painful, unworthy, and unprofitable. Avoiding these two extremes, the Buddha has realized the Middle Path: it gives vision, it gives knowledge, and it leads to calm, to insight, to awakening, to nirvana. [73]

Fig. 226 – The Buddha depicted under the Bodhi tree (c. 800 AD) (Trish Mayo, CC BY 2.0; Brooklyn Museum)

After this realization, Gautama approached the Bodhi-tree (“The Tree of Awakening”). According to the Nidanakatha, from the 5th century AD, he first positioned himself on the southern side of the tree. Instantly the southern half of the world sank until it touched the lowest hell, while the northern side rose to the highest heaven. “This cannot be the place for the attainment of supreme wisdom,” he thought. After trying two other sides with the same result, he came to the east side. He sat down, and here the earth did not move. Gautama said to himself:

This is the Immovable Spot on which all the Buddha’s have established themselves. This is the place for destroying passion’s net. [...] Let my skin, sinews, and bones become dry and welcome; and let all the flesh and blood of my body dry up; but never from this seat will I stir until I have attained the supreme and absolute wisdom! [72]

He had come at last to the supporting midpoint of the universe, which is a metaphor for that point of balance in the mind from which the universe can be perfectly regarded.

Then a demon appeared, first as Lord Desire (Kama), bearing a flowery bow, and then as Lord Death (Mara), king of the demons:

The one who is called in the world the Lord Desire, the owner of the flowery shafts who is also called the Lord Death and is the final foe of spiritual disengagement, summoning before himself his three attractive sons, Mental-Confusion, Gaiety and Pride, and his voluptuous daughters, Lust, Delight, and Pining, sent them before the Blessed One. Taking up his flowery bow and his five infatuating arrows, [he went] to the foot of the tree where the Great Being was sitting. Toying with an arrow, the god showed himself and addressed the calm seer who was there making the ferry passage to the farther shore of the ocean of being.

“Up, up, O noble prince!” he ordered, with a voice of divine authority. “Recall the duties of your caste and abandon this dissolute quest for disengagement. The mendicant life is ill-suited for anyone born of a noble house; but rather, by devotion to the duties of your caste, you are to serve the order of the good society, maintain the laws of the revealed religion, combat wickedness in the world, and merit thereby a residence in the highest heaven as a god.” The Blessed One failed to move.

“You will not rise?” then said the god. He fixed an arrow to his bow. “If you are stubborn, stiff-necked, and abide by your resolve, this arrow that I am notching to my string, which has already inflamed the sun itself, shall be let fly. It is already darting out its tongue at you, like a serpent.” And, threatening, without result, he released the shaft without result. “He does not notice even the arrow that set the sun aflame! Can he be destitute of sense? He is worthy neither of my flowery shaft, nor of my daughters: let me send against him my army.”

And immediately putting off his infatuating aspect as the Lord Desire, that great god became the Lord Death, and around him an army of demonic forms crystallized, wearing frightening shapes and bearing in their hands bows and arrows, darts, clubs, swords, trees, and even blazing mountains; having the visages of boars, fish, horses, carnets, asses, tigers, bears, lions and elephants; one-eyed, multi-faced, three-headed, pot-bellied, and with speckled bellies; equipped with claws, equipped with tusks, some bearing headless bodies in their hands, many with half-mutilated faces, monstrous mouths, knobby knees, and the reek of goats; copper red, some clothed in leather, others wearing nothing at all, with fiery or smoke-colored hair, many with long, pendulous ears, having half their faces white, others having half their bodies green; red and smoke-colored, yellow and black; with arms longer than the reach of serpents, their girdles jingling with bells: some as tall as palms, bearing spears, some of a child’s size with projecting teeth; some with the bodies of birds and faces of rams, or men’s bodies and the faces of cats; with disheveled hair, with topknots, or half bald; with frowning or triumphant faces, wasting one’s strength or fascinating one’s mind. Some sported in the sky, others went along the tops of trees; many danced upon each other, more leaped about wildly on the ground. One, dancing, shook a trident; another crashed his club; one like a bull bounded for joy; another blazed out flames from every hair. And then there were some who stood around to frighten him with many lolling tongues, many mouths, savage, sharply pointed teeth, upright ears, like spikes, and eyes like the disk of the sun. Others, leaping into the sky, flung rocks, trees, and axes, blazing straw as voluminous as mountain peaks, showers of embers, serpents of fire, showers of stones. And all the time, a naked woman bearing in her hand a skull, flittered about, unsettled, staying not in any spot, like the mind of a distracted student over sacred texts.

He roused against him the fury of the winds. Fierce gales rushed toward him from the horizon, uprooting trees, devastating villages, shaking mountains, but the hero never moved; not a single fold of his robe was disturbed. The Evil One summoned the rains. They fell with great violence, submerging cities and scarring the surface of the earth, but the hero never moved; not a single thread of his robe was wet. The Evil One made blazing rocks and hurled them at the hero. They sped through the air but changed when they came near the tree, and fell, not as rocks, but flowers. Mara then commanded his army to shoot their arrows at his enemy, but the arrows, also, turned into flowers. The army rushed at the hero, but the light he diffused acted as a shield to protect him; swords were shivered, battle-axes were dented by it, and whenever a weapon fell to the ground, it, too, at once changed into a flower.

more shaken than the wits of Garuda, the golden-feathered sun-bird, among crows. And a voice cried from the sky: “O Mara, take not upon thyself this vain fatigue! Put aside your malice and go in peace! For though fire may one day give up its heat, water its fluidity, earth its solidity; never will this Great Being, who acquired the merit that brought him to this tree through many lifetimes in unnumbered eons, abandon his resolution.” And the god, Mara, discomfited, together with his army, disappeared. [60]

Gautama had overcome the temptations of lust and social duty and the fear of death. At that moment, he achieved enlightenment (nirvana) and became a Buddha (an “Awakened One”):

Heaven, luminous with the light of the full moon, then shone like the smile of a maid, showering flowers, the petals of flowers, bouquets of flowers, freshly wet with dew, on the Blessed One; the earth quaked in its delight, like a woman thrilled. The gods descended from every side to worship the Blessed One that was now the Buddha, the Wake. “O glory to thee, illuminate hero among men,” they sang, as they walked around him. And the demons of the earth, even the sons and daughters of Mara, the deities who roam the sky and those that walk the ground—all arrived. And after worshiping the victor with the various forms of homage suitable to their stations, they returned, radiant with a new rapture, to their sundry abodes. He had found what he had set forth to seek. He was awake: “the one who had seen.” He was the Buddha.

After sitting in meditation for seven days, he considered staying immobile forever, believing it was unlikely that any human being would be able to understand his message, but finally he was convinced by the gods to preach.

His attainment of enlightenment was interpreted as more than just a personal success story. Instead, it was seen as having cosmic consequences, and his subsequent teachings, the dharma, were interpreted as equal to the laws of the cosmos itself. In this role, the Buddha was often called the Tathagata, a word of uncertain meaning that can be read both as “the one thus come” and “the one thus gone,” perhaps suggesting the illusory nature of his appearance and departure from this plane of existence.

In the last few decades of his life, the Buddha taught what he had learned. Around his eightieth birthday, he lay down on his side and gently passed on. At that moment, he reached paranirvana (“complete extinction”) as the fire of his ego finally flickered out completely. After some time had passed, Gautama’s student Ananda recorded the Buddha’s sermons during a meeting of monks known as the First Buddhist Council.

The practical teachings of the Buddha

Despite the mythological nature of his biography, the teachings of the Buddha—as preserved in the Sri Lankan Pali Canon from the 3rd century BC—are surprisingly practical and reasonable. Whereas the knowledge of the Vedas was “heard” by rishis and had to be accepted on faith, the Buddha told his students not to blindly accept his teachings, but to verify them with their own direct experience. He deemed this necessary, for the goal of the Buddha was not to have his disciples agree with him, but for them to achieve liberation themselves. For example, when a number of villagers expressed confusion about the multitude of contradicting philosophies in circulation, the Buddha remarked not to accept any teaching based solely on the authority or the apparent competence of the teacher. He spoke:

It is fitting for you to be perplexed, O Kalamas, it is fitting for you to be in doubt. Doubt has arisen in you about a perplexing matter. Come, Kalamas. Do not go by oral tradition, by lineage of teaching, by hearsay, by a collection of texts, by [apparent] logic, […] by the acceptance of a view after pondering it, by the seeming competence of a speaker, or because you think, “The ascetic is our teacher.” But when you know for yourselves, “These things are unwholesome; these things […], if undertaken and practiced, lead to harm and suffering,” then you should abandon them. [74]

Since beginners aren’t immediately able to verify the Buddha’s more complex teachings, he was content with teaching them the few things they could directly verify and to move from there. For instance, when the villagers questioned whether it was possible to be reborn in heaven by doing good deeds, the Buddha remarked there was no need to know the answer up front, for the benefits of good deeds would also be evident in this life. He spoke:

If there is another world, and if good and bad deeds bear fruit and yield results, it is possible that with the breakup of the body, after death, I shall arise in a good destination, in a heavenly world. […] If there is no other world, and if good and bad deeds do not bear fruit and yield results, still right here, in this very life, I live happily, free of enmity and ill will.

On various occasions, when the Buddha was questioned about the nature of the universe, he bluntly refused to answer, since answers to these questions were not necessary for achieving enlightenment. We read:

These speculative views have been left undeclared by the Blessed One, set aside and rejected by him, namely: “the world is eternal” and “the world is not eternal;” “the world is finite” and “the world is infinite;” “the soul is the same as the body” and “the soul is one thing and the body another;” and “after death a Tathagata exists” and “after death a Tathagata does not exist” and “after death a Tathagata both exists and does not exist” and “after death a Tathagata neither exists nor does not exist.”

To explain his position, the Buddha used the analogy of a man shot by an arrow, who instead of wanting the arrow removed, proceeded to ask abstract questions about it. We read:

Suppose, Malunkyaputta, a man was wounded by an arrow thickly smeared with poison, and his friends and companions, his kinsmen and relatives, brought a surgeon to treat him. The man would say: “I will not let the surgeon pull out this arrow until I know whether the man who wounded me was a khattiya, a brahmin, a merchant, or a worker.” And he would say: “I will not let the surgeon pull out this arrow until I know the name and clan of the man who wounded me; […] until I know whether the man who wounded me was tall, short, or of middle height; […] until I know whether the bow that wounded me was a long bow or a crossbow; […] until I know whether the bowstring that wounded me was fiber, reed, sinew, hemp, or bark; […] until I know with what kind of feathers the shaft that wounded me was fitted—whether those of a vulture, a heron, a hawk, a peacock, or a stork; […] until I know what kind of arrowhead it was that wounded me—whether spiked or razor-tipped or curved or barbed or calf-toothed or lancet-shaped.” All this would still not be known to that man, and meanwhile he would die.

He continued:

Whether there is the view “the world is eternal” or the view “the world is not eternal,” there is birth, there is aging, there is death, there are sorrow, lamentation, pain, dejection, and despair, the destruction of which I prescribe here and now.

Why have I left [these questions] undeclared? Because it is unbeneficial, it does not belong to the fundamentals of the spiritual life, it does not lead to disenchantment, to dispassion, to cessation, to peace, to direct knowledge, to enlightenment, to nirvana. That is why I have left it undeclared. And what have I declared? “This is suffering”—I have declared. “This is the origin of suffering”—I have declared. “This is the cessation of suffering”—I have declared. “This is the way leading to the cessation of suffering”—I have declared. [These being the Four Noble Truths we will encounter in a moment]

On another occasion, he rejected a similar abstract question by a monk named Vaccha, but this time because it was unanswerable:

“When a monk’s mind is liberated thus, Master Gautama, where is he reborn [after death]?” “Is reborn does not apply, Vaccha.” “Then he is not reborn, Master Gautama?” “Is not reborn does not apply, Vaccha.” “Then he both is reborn and is not reborn, Master Gautama?” “Both is reborn and is not reborn does not apply, Vaccha.” “Then he neither is reborn nor is not reborn, Master Gautama?” “Neither is reborn nor is not reborn does not apply, Vaccha.”

Vaccha was confused by the answer, so the Buddha clarified his position with a metaphor:

“What do you think, Vaccha? Suppose a fire were burning before you. Would you know: ‘This fire is burning before me?’” “I would, Master Gautama.” [...] “If that fire before you were to be extinguished, would you know: ‘This fire before me has been extinguished?’” “I would, Master Gotama.” “If someone were to ask you, Vaccha: ‘When that fire […] was extinguished, to which direction did it go: to the east, the west, the north, or the south?’—being asked thus, what would you answer?” “That does not apply, Master Gautama.”

So just as the fire hasn’t gone anywhere, so too will the Buddha simply be extinguished (nirvana). [74]

On top of all this, the Buddha asked his students to test him to ensure he practiced what he preached:

A monk who is an inquirer […] should make an investigation of the Tathagata in order to find out whether or not he is perfectly enlightened.

His students should check whether he has truly overcome fear, desire, and the temptation of fame. He also told them to only accept teachings that are clear and openly taught, without secrecy.

Life is Suffering

So, what starting point did the Buddha recommend for his students? He asked his students to take a direct and uncompromising look at the nature of reality—especially at the fact that we are all destined to grow old and die. The Buddha knew humans have a hard time learning this lesson. To make this clear, he related the following story about a doomed man appearing before King Yama, Lord of the Dead:

Then, monks, King Yama questions that man, examines him, and addresses him concerning the first divine messenger: “Didn’t you ever see, my good man, the first divine messenger appearing among humankind?” And he replies: “No, Lord, I did not see him.” Then King Yama says to him: “But, my good man, didn’t you ever see a woman or a man, eighty, ninety, or a hundred years old, frail, bent like a roof bracket, crooked, leaning on a stick, shakily going along, ailing, youth and vigor gone, with broken teeth, with gray and scanty hair or bald, wrinkled, with blotched limbs?” And the man replies: “Yes, Lord, I have seen this.” Then King Yama says to him: “My good man, didn’t it ever occur to you, an intelligent and mature person, ‘I too am subject to old age and cannot escape it. Let me now do noble deeds by body, speech, and mind’?” “No, Lord, I could not do it. I was negligent.”

The main reason for this misunderstanding, the Buddha taught, was that on some level we cannot help but believe that the state of our current life will be permanent. An ignorant man, he claimed, did not think: “This gain that has come to me is impermanent, bound up with suffering, subject to change.” As a result, we allow ourselves to become attached to objects in the world and to our own identity. But since everything eventually perishes, this inevitably leads to suffering. In his unassuming language, he spoke:

“What do you think, monks, is form permanent or impermanent?” “Impermanent, venerable sir.” “Is what is impermanent suffering or happiness?” “Suffering, venerable sir.” “Is what is impermanent, suffering, and subject to change fit to be regarded thus: ‘This is mine, this I am, this is my self?’” “No, venerable sir.”

To get this message across, the Buddha regularly used powerful graphic metaphors. In one of his early sermons, the Fire Sermon, he discussed this idea with intensity:

Monks, all is burning. And what is the all that is burning? Monks, the eye is burning, visible forms are burning, visual consciousness is burning [...] Burning with what? Burning with the fire of lust, with the fire of hate, with the fire of delusion. [75]

On another occasion, he compared the number of tears and bloodshed that each of his disciples must have shed throughout their countless lives to the size of the oceans:

What do you think, monks, which is more: the stream of tears [or “stream of blood” in another version] that you have shed as you roamed and wandered through this long course, weeping and wailing because of being united with the disagreeable and separated from the agreeable—this or the water in the four great oceans? [...] For a long time, monks, you have experienced the death of a mother; […] the death of a father; [...] the death of a brother; [...] the death of a sister; [...] the death of a son; [...] the death of a daughter; [...] the loss of relatives; [...] the loss of wealth; [and] loss through illness; […] It is enough to experience revulsion toward all formations, enough to become dispassionate toward them, enough to be liberated from them.

Even more graphic were his meditations on the death and decay of the body. On one occasion, he asked his monks to meditate on the thought of a beautiful young girl growing old, dying, and then having her body go through various stages of decay:

One might see that same woman as a corpse thrown aside in a charnel ground, one, two, or three days dead, bloated, livid, and oozing matter. What do you think, monks? Has her former beauty and loveliness vanished and the danger become evident?

Then we read of her body as “devoured by crows, hawks, vultures, dogs, jackals, or various kinds of worms” and then as “a skeleton with flesh and blood,” then as “a skeleton without flesh and blood, held together with sinews,” as “disconnected bones scattered in all directions—here a hand-bone, there a foot-bone, here a shin-bone, there a thigh-bone, here a hip-bone, there a back-bone, here the skull,” as “bones bleached white, the color of shells,” as “bones heaped up,” and finally as “bones more than a year old, rotted and crumbled to dust.” In another version of this meditation, the monks are each time asked to compare the corpse to their own body: “This body too is of the same nature, it will be like that, it is not exempt from that fate.”

The Four Noble Truths

In his first sermon after attaining enlightenment—famously delivered at the deer park at Isipatana—the Buddha taught how to escape from the suffering in the world. The sermon is called The Setting in Motion of the Wheel of the Dharma, marking the moment the wisdom of his teachings (his dharma) was shared with the public. In the sermon, he summarized his teaching with Four Noble Truths. We read:

Now this, monks, is the noble truth of suffering (dukka): birth is suffering, aging is suffering, illness is suffering, death is suffering; union with what is displeasing is suffering; separation from what is pleasing is suffering; not to get what one wants is suffering; [...]

Now this, monks, is the noble truth of the origin of suffering: it is craving which leads to re-becoming, accompanied by delight and lust, seeking delight here and there; that is, craving for sensual pleasures, craving for becoming, craving for disbecoming.

Now this, monks, is the noble truth of the cessation of suffering: it is the fading away and cessation of that same craving, the giving up and relinquishing of it, freedom from it, non-reliance on it.

Now this, monks, is the noble truth of the way leading to the cessation of suffering: it is the Noble Eightfold Path; that is, right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. [75]

Or in short:

1 All life is suffering

2 Craving is the cause of this suffering.

3 There is a way out.

4 The way out is the Noble Eightfold Path.

The Noble Eightfold Path was the Buddha’s path to salvation. It is often symbolized by an eight-spoked wheel. The first spoke is called right view and is about understanding the path to nirvana. The second is right intentions, which is about giving up your home and staying away from cruelty and sensuality. The third spoke is called right speech, which is about refraining from lying and rude language, instead saying things that lead to salvation. The fourth spoke is called right action and is about not killing, injuring, stealing, or having sex. The fifth spoke is called right livelihood and is about begging for food and only possessing what is necessary to sustain life. The sixth spoke is called right effort and is about guarding yourself against sensual, evil, and immoral thoughts.

The seventh spoke is called right mindfulness (sati). It is about having a lucid awareness of every perception, thought, and feeling that presents itself in the present moment. It is about experiencing things as they are without adding excess meaning and without getting swept away by them. By doing this, we can avoid desires and fears from distorting our view of reality. In one of the early texts, we read:

And what is right mindfulness? Here the monk remains contemplating the body as body, resolute, aware and mindful, having put aside worldly desire and sadness; he remains contemplating feelings as feelings; he remains contemplating mental states as mental states; he remains contemplating mental objects as mental objects, resolute, aware, and mindful, having put aside worldly desire and sadness; This is called right mindfulness. [74]

This act of simple observation is also described here:

Here, for a monk, feelings are understood as they arise, as they remain present, as they pass away. Thoughts are understood as they arise, as they remain present, as they pass away. Perceptions are understood as they arise, as they remain present, as they pass away. It is in this way that a monk exercises clear comprehension.

Fig. 228 – Buddha giving his first sermon in the deer park, holding the eight-spoked wheel (The MET)

The mindfulness of feelings was described as follows in more detail:

Here, when feeling a pleasant feeling, a monk understands: “I feel a pleasant feeling;” when feeling a painful feeling, he understands: “I feel a painful feeling;” when feeling a neutral feeling, he understands: “I feel a neutral feeling.”

With these investigations, we can, for instance, discover that we often respond to painful feelings with exaggerated negative beliefs, which produce even more negative feelings, creating unnecessary suffering. This is a very profound psychological insight. We read:

Monks, when the uninstructed worldling experiences a painful feeling, he sorrows, grieves, and laments; he weeps beating his breast and becomes distraught. He feels two feelings—a bodily one and a mental one. Suppose they were to strike a man with a dart, and then strike him immediately afterward with a second dart, so that the man would feel a feeling caused by two darts. So too, when the uninstructed worldling experiences a painful feeling, he feels two feelings—a bodily one and a mental one […] Monks, when the instructed noble disciple experiences a painful feeling, he does not sorrow, grieve, or lament; he does not weep beating his breast and become distraught. He feels one feeling—a bodily one, not a mental one.

The Buddha considered “concentration gained through mindfulness of breathing” to be the most important meditation for the attainment of enlightenment. He even called it “the Tathagata’s dwelling.” He described it as follows:

Simply mindful he breathes in, mindful he breathes out. When a monk breathes in long, he knows, “I breathe in long;” and when he breathes out long, he knows, “I breathe out long.” Breathing in short, he understands: “I breathe in short;” or breathing out short, he understands: “I breathe out short.” He trains thus: “I will breathe in experiencing the whole body;” he trains thus: “I will breathe out experiencing the whole body.” He trains thus: “I will breathe in tranquilizing the bodily formation;” he trains thus: “I will breathe out tranquilizing the bodily formation.”

Fig. 229 – A statue of the (1st-2nd century AD) (World Imaging; Tokyo National Museum)

But alternatively, mindfulness can also be attained during simple activities:

Again, monks, when walking, a monk understands: “I am walking;” when standing, he understands: “I am standing;” when sitting, he understands: “I am sitting;” when lying down, he understands: “I am lying down;” or he understands accordingly however his body is disposed.

And then finally, the eighth spoke is called right concentration (samadhi) and is about practicing meditation, where one focuses the attention of the mind on one object. This clears and calms the mind and eventually leads to enlightenment (nirvana).

The doctrine of not-self

In his second sermon, known as the Characteristics of Not-Self (anatman), the Buddha claimed that the self (atman) cannot be found in the five aggregates, which include material forms, feelings, perceptions, the will, and consciousness. These aspects cannot belong to the self, he explained, since they are subject to change. If we nevertheless decide to cling to them, we will necessarily experience suffering when they eventually disappear. The reverse is also true. Detaching ourselves from the five aggregates brings enlightenment.

Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka

Both the teachings of Jainism and Buddhism spread widely, especially since they were open to anyone, independent of caste. A few centuries later, the teachings were even picked up by two great leaders of the Mauryan dynasty. The Mauryan empire was founded by Chandragupta Maurya (c. 321–297 BC), who first ruled a kingdom in North India. When other northern kingdoms were weakened by the armies of Alexander, Chandragupta moved in and established his empire. In 305 BC, he clashed with Seleucus, Alexander’s successor in Asia, winning back the Indian territory from the Greeks. After the battle, Seleucus sent a diplomat named Megasthenes (c. 350–290 BC) to Chandragupta’s court, who lived there for four years. Unfortunately, the record of his experiences has been lost, but parts of his text have been paraphrased by others. We read of a capital city guarded by 600 towers, fortified gateways, and a vast wooden palace from which Chandragupta controlled his administration, all without a written record. To the surprise of many, Chandragupta eventually gave up his throne to become a Jain, perhaps after realizing the horrors of the wars he had waged. Tradition has it that he then ended his life by fasting to death to burn off his bad karma.

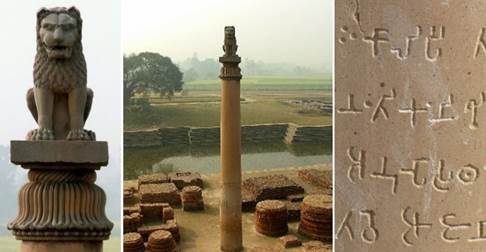

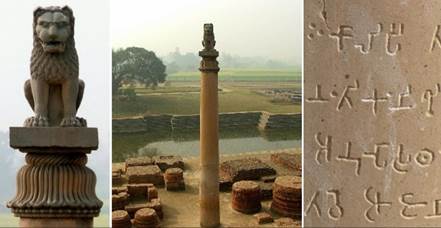

His grandson Ashoka (ruled c. 268–232 BC) was another great leader. He, too, was first a victorious conqueror but then became known for his dedication to non-violence and benevolence. Using the new Brahmi script, he wrote a message on stone pillars across his kingdom, telling his subjects he had turned to Buddhism after leading his army to victory in a bloody war (see Fig. 230). In his inscription, he did not speak of nirvana, but he did talk about protecting the poor and the weak. He also made the site of his bloodiest battle a center where Buddhists could assemble and pray and send out missionaries to persuade his people to follow the Buddhist dharma. Ashoka also organized the Third Buddhist Council, at which the standard Buddhist text, the Pali Canon, was codified in the Pali language.

Fig. 230 – One of Ashoka’s pillars (mself, CC BY-SA 2.5; Bpilgrim, CC BY-SA 2.5; Wikimedia; CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Mahayana

A few centuries later (the exact date is unknown), a group of monks became dissatisfied with the idea that enlightenment was only available to a small elite who made meditation their full-time occupation. As a result, they created a new version of Buddhism applicable to a wider audience. The result was Mahayana Buddhism (as opposed to the traditional Theravada Buddhism). Mahayana means “Great Ferry,” in reference to the great number of people it promised to take to enlightenment. It is this type of Buddhism that eventually spread to China, Tibet, Japan, and many other places in the East.

Although Mahayana was, historically, a new development, its followers were quick to rewrite history to make their ideas seem like the original teaching of the Buddha. They claimed that the Buddha had met in secret with a group of so-called bodhisattvas (meaning “one whose being is enlightenment”). The story goes that the Buddha presented them with his final teaching, which they had to keep secret until the world was ready to receive it.

A bodhisattva is sometimes described as a person who is about to become a Buddha in this lifetime or in just a couple of lives but who, along his path, is also willing to help others ahead. At other times he is described as a person who has already achieved Buddhahood but who, before forever disappearing into the void of nirvana, is willing to stick around to help others reach nirvana as well. Bodhisattvas do this out of an all-embracing compassion for all beings who are suffering. We read:

May I achieve Buddhahood for the sake of all other beings!

In some ways, Mahayana turned Buddhism into a popular religion. Some bodhisattvas were believed to have become powerful gods who bestowed their grace as an act of compassion on whoever chanted their name. This turned a path based on self-reliance into a path of asking favors by praying to an external god. A well-known example is Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, who weeps as he sees the suffering of the world. His compassion can be invoked by chanting the mantra “om manipadme hum” (“Ah, the jewel in the lotus”). Interestingly, in China, this character was described as female. Another example is Maitreya, the Buddha of the future, who is waiting in one of the heavens until the time is right for him to teach, but people can already invoke his aid. A Chinese monk named Budai (in Japanese, Hotei) claimed to have been his incarnation. Due to his jolly character and his weight, this monk is often called the Laughing or the Fat Buddha. The Buddha Amitabha (“Buddha of Infinite Light”) was believed to have created his own divine realm, Sukhavati (“Pleasurable”), where he sits on a lotus throne. Anyone who chants his name with faith, especially at the moment of death, is said to be reborn in his land in a lotus bud. This bud finally opens when the person is ready to experience enlightenment.

Emptiness

The Mahayana Buddhists also developed the concept of emptiness (shunyata). Traditional Buddhism had taught that the self could not be found in the five aggregates, but Mahayana Buddhism took this a step further. It even denied the reality of the self, which they also regarded as impermanent.[3] As a result, they claimed, all of nature was, in essence, emptiness. We therefore read:

All existence whatsoever is unsubstantial.

It is our ignorance that makes us believe we have an “I,” which is the cause of both our fears and our desires. In reality, no such thing exists.

When the Buddha, according to Mahayana tradition, saw others still attached to their apparent sense of self, he responded with a feeling of compassion (karuna) for all beings. Ironically, however, he also realized that these beings were, in reality, not beings at all. And it was for this reason that the Buddha, in the words of the mythologist Joseph Campbell, spent most of his time “compassionately teaching what cannot be taught to others who did not exist.”

This view of the world is also beautifully described by the following lines from the Diamond Sutra (written somewhere in the first centuries AD):

Stars, darkness, a lamp, a phantom, dew, a bubble; a dream, a flash of lightning, and a cloud: thus should we look upon the world. [60]

The key to Mahayana Buddhism is the realization that the atman does not need salvation, since it does not exist. Since everything is essentially empty, there can’t even be an essential difference between the Buddha and ourselves, between samsara and nirvana, between the tumult of this world and the peace of the void. All are equally empty. In a sense, therefore, we are already identical to the Buddha and are already experiencing nirvana. To become the Buddha simply means to recognize this. The world is already enlightened. Or phrased differently:

All things are Buddha things. [60]

This view of the world creates a rather pleasant paradox. A monk can decide to take life seriously and strive to become the Buddha, yet he can, at the same time, realize that everything is just an illusion, making him not bound by any of it. He is participating with irony in the world’s illusion, seeing duality yet knowing it to be deceptive. It is this attitude that gives a kind of lightness to the serious practitioner of Mahayana Buddhism.