Around the time when the forest philosophers of India created the ideal of the selfless renouncer, the Greeks instead gave their place of highest esteem to the great warriors, who fought on the battlefield in search of eternal glory. Bards recited long poems about the achievements of legendary heroes, the greatest among them being Achilles. In this chapter, we will tell his story.

The Minoan and the Mycenaean civilizations

The Bronze Age in Greece started around 2700 BC with the Minoan civilization on the island of Crete. In their capital, Knossos, the Minoans built a large palace, the remains of which still exist today (see Fig. 263). The palace included multi-level housing—in some places up to four or five stories high. There was a throne room, a ceremonial court, storage rooms, and many other rooms.

Fig. 262 – An acrobat jumping over a bull (Jebulon; Heraklion Archeological Museum, Crete)

Little is known about the religion of the Minoans as their language has not yet been deciphered, but it seems they primarily worshiped goddesses (see Fig. 264). We also find various images of acrobats jumping over bulls, which might have been part of a ritual (see Fig. 262). Around 1400 BC, the civilization disappeared for reasons yet unknown.

Around 1750 BC, the Mycenaean civilization appeared on mainland Greece, formed by Indo-European migrants. They founded a number of cities whose names we recognize to this day, such as Athens, Thebes, and Troy. In their writings, we have also found the names of familiar gods and goddesses, such as Zeus, Athena, Poseidon, and Dionysus.

Fig. 263 – Remains of the palace at Knossos (S. P. Dinkgreve, worldhistorybook.com; Crete)

Fig. 264 – Minoan goddess with snakes (C. Messier, CC BY-SA 4.0; Heraklion Archeological Museum, Crete)

Fig. 265 – A golden Mycenaean death mask (Xuan Che, CC BY 2.0; National Archeological Museum, Athens)

Mycenaean culture was aggressive. Their cities had massive fortifications, suggestive of much conflict between the cities. They built walls of massive limestone blocks, some six meters long and weighing 50 tons. Later Greeks were so amazed by these structures, that they assumed they were made by Cyclops. The Mycenaean chiefs were buried in large corbelled rooms, named beehive tombs, containing rich grave goods, including gold ceremonial swords and death masks (see Fig. 265). The Mycenaean culture collapsed around 1200 BC, likely as part of the Bronze Age Collapse (see the chapter “The Divine Kings”).

Fig. 266 – The Lion’s gate at the citadel of Mycenae (1250 BC) (Joyofmuseums; CC BY 4.0)

Fig. 267 – The Treasury of Atreus at the citadel of Mycenae (14th-13th centruy BC) (delta-kapa, Dimitrios Katsamakas, CC BY 4.0)

Homer

The Mycenaean period was followed by a period of decline called the Greek Dark Ages, which was followed in the 8th century BC by a period called Archaic Greece. In this period, a traveling bard named Homer supposedly wrote down two epic poems known as the Iliad (c. 750) and the Odyssey (c. 720 BC), which became the earliest literary works in the European tradition and the main cultural texts of ancient Greece. The differences in both texts, however, are so great both in terms of vocabulary, theology, ethics, and narrative style, that it is unlikely they were actually written down by the same author.

The story of the Iliad likely predates the Archaic Period, as it contains many hints of a much earlier age, suggesting the story must have been transmitted orally for centuries before Homer finally committed it to paper. To give one obvious example, the weapons mentioned in the Iliad are bronze, while the Iron Age in Greece had already started around 1300 BC.

Although they mention gods, the Iliad and the Odyssey cannot be regarded as religious texts, as they contain no absolute truths that people were expected to believe in. In both texts, the bard does invite the Muses to help him memorize the words of the story, but these were goddesses associated with poets, and not with priests. This reflects a trend fundamental to ancient Greece, namely that much of their cultural heritage was not formulated by priests or prophets, but by artists, poets, and philosophers. The Greeks obviously had strong religious views, as any other civilization at the time, yet there was no institution designed to impose an orthodoxy. There were priests responsible for public sacrifices, but they did not busy themselves with ethical commandments and had no sacred scripture they demanded people to believe in. Instead, the Iliad and the Odyssey served mainly as entertainment and as a way to impart life lessons, as the characters served as role models for proper and improper behavior.

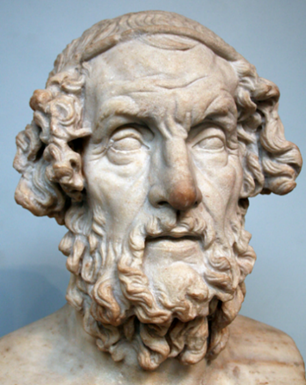

Fig. 268 – Homer (2nd century BC) (JW1805; British Museum)

Imperishable glory

The Homeric epics are set in the Mycenaean period, which the Archaic Greeks glorified as a heroic age of magnificent warriors. In their view, warriors lead the most fulfilling lives, as war can awaken in people an experience of ecstasy (ekstasis). In contrast, a peaceful life was regarded as a waste of one’s only time on earth.

Since the Greek version of the afterlife was not something to look forward to, getting the most out of life was especially important to them. Similar to the Mesopotamians, they believed that the soul (psyche) descends to the underworld after death, where it leads an empty existence. When Odysseus visited the underworld in the Odyssey, he was horrified to find that the dead did not even remember their own names. To get Achilles to remember his life on earth, Odysseus had to sacrifice an animal and feed Achilles’s ghost with its blood. Odysseus then told him:

No man has ever been more blessed than you in days past, or will be in days to come. For before you died, we Achaeans honored you like a god, and now in this place, you lord it among the dead.

Yet Achilles’ response was less positive:

Don’t gloss over death to me in order to console me. I would rather be above ground still and laboring for some poor peasant man than be the lord over the lifeless dead. [105]

This is the tragedy of the Greek hero. No matter his accomplishments, he was fated to die, after which he was doomed to lead a meaningless existence in the underworld. As a result, the Greeks came to believe that the only way to live a meaningful life was to be remembered by future generations. To attain this, the Greeks fought for honor (timê) and glory (kleos). Timê specifically referred to the booty obtained from heroic exploits. Kleos referred to other people speaking well of you, which the Greeks believed could be obtained by killing and finally being killed in an honorable fight. The ultimate form of kleos was called kleos aphthiton (“imperishable glory”), which meant to be remembered for all time. According to the Greeks, this was the only form of immortality available to mortal men. It was the best a mortal man could attain.

The Olympian gods

Adding to the tragedy of the story, the mortality of the Greeks was powerfully contrasted with the immortality of the gods. Being immortal, the gods had no need for kleos. They did not have to worry about being remembered, because they would continue to exist forever. For that reason, two Trojan fighters in the Iliad admitted they wouldn’t bother fighting if they were immortal:

Supposing you and I, escaping this battle, would be able to live on forever, ageless, immortal, so neither would I myself go on fighting in the foremost, nor would I urge you into the fighting where men win glory (kleos). But now, seeing that the spirits of death stand close about us in their thousands, no man can turn aside or escape them, let us go on and win glory (kleos) for ourselves, or yield it to others. [106]

While the Greeks were fighting to the death, as “wretched mortal men […] who live in pain” the gods of the Iliad are described as having an easy life, “living without a care.” Although the human characters in the story are always in awe of their incredible power, the reader also gets to see the lives of the gods as rather trivial. Some scenes even feel like comic relief. The gods regularly fight among themselves, lie to each other, and in one scene, Hera has sex with Zeus to get him to fall asleep so she can help the Greeks behind his back. The gods also complain about minor injuries, some caused by human beings. For instance, at some point the warrior Diomedes, supported by the goddess Athena, wounded both the goddess Aphrodite and the god Ares:

Diomedes wounded Ares, piercing his fair skin. […] Ares, in a rush, went to the gods’ home, steep Olympus, sat by Zeus, distressed at heart. He showed Zeus where he was wounded, dripping with immortal blood. [107]

Because of their easy life, the gods are also often incapable of truly feeling the suffering of human beings. Being immortal, they just had no real stakes in the game. For instance, when Achilles’s best friend died, Zeus only felt a momentary pity, in stark contrast with the unbearable grief of Achilles. Ironically, Zeus did pity the weeping immortal horses of Achilles for having to grieve over a mortal man:

Poor wretches, why then did we ever give you to the lord Peleus [Achilles’ father], a mortal man, while you yourselves are immortal and ageless? Only so that among unhappy men you also might be grieved? Since among all creatures that breathe on earth and crawl on it, there is not anywhere a thing more dismal than man is. [106]

Despite all our shortcomings, there was one small upside to being a mortal human—the very fact that we know we are going to die allows us to experience nobility, courage, and self-sacrifice, which are virtues that we prize highest and that give meaning to our lives.

Moira

The Greeks of the Iliad were never truly in charge of their own destiny since the gods always pulled the strings behind the scenes. In fact, all the important events in the Iliad are described from the point of view of the struggling humans on earth, but then the audience is shown how the gods made these events happen. In the end, we learn it is the gods who start quarrels among men, lead armies into battle, plan the strategy of war, speak to soldiers at crucial moments, tell leading figures what to do, and so on. When a warrior survived a stabbing, we later read that a god had made the weapon avoid his vital organs. When Achilles was angry at his superior Agamemnon, it was a god who grabbed him by the hair and warned him not to strike him. When a warrior in battle became possessed by a god, he would experience a divine power that made him kill anything that stood in his way. The Greeks called this experience aristeia (literally meaning “excellence”).

To some modern readers, the high degree of control by the gods can devalue the actions of the heroes. Today we like our heroes to be in charge of their own destiny so they can take full credit for their accomplishments. In the Iliad this is not the case. On various occasions, the gods in the story even tell us upfront what the final fate (moira) of the characters is going to be. Moira literally means “portion,” referring to the “amount of life” given to each individual. Each Greek was believed to have a fixed time of death, at which time the person was said to have “met his fate.” Interestingly, even the gods were not able to change fate.

This narrative choice heightens the tragedy of the story. Already knowing the ending of the story, we listen with dread as we see the events unfolding to their inevitable tragic conclusions. Meanwhile, the mortal characters in the story are unaware of their fate, trying to do everything in their power to turn destiny in their favor.

Fig. 269 – Remains of the walls of Troy in modern-day Turkey. (CherryX, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The psychology of the Iliad

There has been much speculation about whether the lack of free will in the Iliad reflects the actual worldview of people at the time, or whether it is just a ploy used to enhance the tragic effect of the story. If the former is true, the Iliad is a “psychological document of immense importance” (in the words of the controversial writer Julian Jaynes). Interestingly, compared to later Greek texts, there is barely a sense of introspection in the Iliad. Instead, the inner world is mostly hijacked by the gods. Almost never do we read of the private thoughts going on inside the minds of the characters. Even words that would later refer to the mind were here used differently. For instance, the word “thumos,” which later came to refer to the emotional mind, here often simply meant “energy” (for example, someone stops moving when his thumos leaves his limbs and thumos can also urge a man into action or make him want to eat, drink, or fight). In the Iliad, we never read that thoughts occur in the thumos, yet the gods can “cast vigor” into it. The word “phrenes” likely first referred to the lungs and the sensation of breathing. In the Iliad it can also hold emotions, such as fear. The word “kradie” can often be interpreted as a change in heart rate. For instance, a coward is not someone who is afraid, but someone whose kradie beats loudly. The word “noos,” which later came to refer to the conscious mind, is here often simply used as “perception.” [29]

There are some rare exceptions to this rule. For instance, Achilles is asked by his mother not to “hide” knowledge in his “noos” and at one point Achilles disapproves of a “man who hides one thing in his heart and speaks another” (although this example has been shown by linguists to have been added at a later date). There is also the word “mermerizo,” meaning “in two parts,” which is often translated as “to ponder.” Yet even here, the choice is always between two external actions and not between two thoughts and the gods usually make the deciding call. For instance, at one point Achilles’s “hairy chest was divided in two, deliberating whether to draw his sharp sword […] or to suppress his bitter anger and subdue his heart.” But when he drew his sword, Athena stepped in (“invisible to all except Achilles”) and stopped him.

The Odyssey is completely different. The fifth word of the text is “polutropon,” literally meaning “much turning,” referring to Odysseus’s great wit. In contrast to the Iliad, this story is much less about the gods and more a celebration of the plans concocted in the mind of this clever individual. The word “thumos” in the Odyssey also comes closer to its later meaning. For instance, we read that the gods helped someone recognize the disguised Odysseus by placing a “recognition” into his “thumos.” We also read that Odysseus deceived the goddess Athena, holding “thoughts of great cunning” in his “noos” (here clearly meaning “mind”).

In the two centuries that followed, the transformation became complete. In Hesiod’s Works and Days, which was written around 700 BC, the word “thumos” became a mental space where information, advice, sights, and mischief could be “put,” “held,” and “kept.” Advice could also be placed in the “phrenes,” where it can be “looked at” carefully. The “noos” now can have shame or can be “without good direction”. Archilochus (c. 680–645 BC), a wandering soldier-poet, even talks of his “thumos” as though it is a separate self within himself. For instance, he asks his “thumos”: “look up and defend yourself against your enemies.” Solon (c. 630–560 BC), whom we will meet later in a chapter on Athenian democracy, tells us that a man can figure out what is just or unjust in his “noos.” A man can also “see” into himself with the “eye” of his “noos” in order to “know himself.” [29] With this capacity for introspection, the gods became less necessary as guides for human action. In fact, Solon warns his fellow Athenians not to blame the gods for their misfortunes, but themselves. This type of personal responsibility was unthinkable in the Iliad.

Troy

Now we understand the proper context of the Iliad, we are ready to discuss the story in some detail. The Iliad is set in the Mycenaean period and describes a pivotal part of the last year of the Trojan War, fought between the Greeks (known as the Achaeans in the Iliad) and the Trojans. Whether such a war actually took place is a matter of debate, but since the rediscovery of Troy in the 19th century, it has at least become plausible.

So, what do we know about Troy? Traditionally, the Trojan War was dated to about 1250 BC, but the Iliad shows evidence from earlier times. For instance, various weapons used in the story were long out-of-date by the 13th century BC. The archeological record is equally inconclusive. Over time, nine cities were built on the archeological site, one on top of the other. The layer named Troy VI was probably destroyed around 1300 BC. It was a wealthy city, with goods imported from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Cyprus, yet evidence suggests an earthquake, and not a war, caused its collapse. Troy VIIa was destroyed around 1180 BC, but this might have been done by the Sea Peoples, who also attacked Egypt around this time.

We can learn more about Troy from Hittite sources. Here, we read that around 1430 BC a confederacy of 22 city-states on the western coast of Turkey, known as Assuwa, rebelled against their Hittite rulers. Among the cities of Assuwa was a place named Wilusiya, which is reminiscent of Ilios (earlier likely called Wilios), which was another name for Troy. In a treaty with the Hittites from around 1280 BC, we even read that a king of Wilusiya was named Alaksandu (Alexander), an alternative name for Prince Paris from the Iliad. Archeologists have also found a Hittite letter, named the Tawagalawa Letter (c. 1250 BC), which is addressed to a king of Ahhiyawa (mainland Greece) and states: “We have come to an agreement on Wilusa over which we went to war.” [39]

Fig. 270 – Menelaos dropping his sword when seeing the beautiful Helen. (Jastrow; Louvre, France)

The two fates of Achilles

The Trojan War started when Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world and wife of the Greek king Menelaos, was abducted by the handsome Trojan prince Paris. Even among ancient Greek authors, it was unclear whether Helen left Menelaos willingly or not. Whatever the case, the various kings of Greece united under the command of Menelaos’s elder brother, King Agamemnon of Mycenae, to bring Helen back home. The war lasted a total of ten years, ending with the fall of Troy.

Achilles was one of the kings under Agamemnon’s command. He was considered the best fighter on the side of the Greeks and headed a group of powerful warriors called the Myrmidons. Achilles owed his superhuman strength to his semi-divine nature, as his mother was the immortal sea goddess Thetis and his father the mortal king Peleus. As a result of his mortal father, Achilles did not inherit his mother’s immortality. This fact tormented both Achilles and his mother. In a number of passages, we find Thetis lamenting the brevity of his life.

His connection to his mother did give Achilles some special knowledge not usually available to mortal men. Thetis informed Achilles that he had not one but two possible fates. He could either decide to win kleos and die in the Trojan War or he could return home and live a long and peaceful, albeit inglorious, life. We read:

For my mother Thetis, the goddess of the silver feet, tells me I carry two sorts of destiny toward the day of my death. Either, if I stay here and fight beside the city of the Trojans, my return home is gone, but my glory shall be everlasting; but if I return home to the beloved land of my fathers, the excellence of my glory is gone, but there will be a long life left for me, and my end in death will not come to me quickly. [106]

This added another layer of tragedy to the story. While many warriors feared they might die at Troy, Achilles knew for sure he would die if he decided to fight.

The wrath of Achilles

Before the war, Achilles had been a man of great love (philotes). We can see this in his warm relationship with his best friend Patroklos, with his mother and father, and his surrogate father Phoinix. Yet, certain events during the war had darkened his soul:

He had made savage the great heart within his chest. [106]

His anger is the main theme of the Iliad. In fact, the first word of the Iliad is “wrath” (“menis”). With the word order changed in modern English, it reads:

Sing, Goddess, sing of the wrath of Achilles, son of Peleus—that murderous anger which condemned Achaeans to countless agonies and threw many warrior souls deep into Hades, leaving their dead bodies as food for dogs and birds—all in fulfillment of the will of Zeus. [107]

The word “menis” was usually used only in reference to the gods, suggesting the superhuman nature of his anger. His wrath was first unleashed when Agamemnon took his concubine, a princess called Briseis. Achilles had acquired her when he sacked a town near Troy. She had become an important part of his timê, but the two had also become fond of each other. Achilles even likened their relationship to that of a husband and wife (“my heart loved that girl, though captured with my spear”). When Agamemnon lost his own concubine, Cryseis, he took Briseis as compensation for his loss. In reaction, Achilles spoke:

I didn’t come to battle over here because of Trojans. I have no fight with them. […] We came with you, to please you, dog face, and for Menelaus. […] You threaten now to confiscate the prize I worked so hard for. […] I don’t fancy staying here unvalued, to pile up riches, treasures just for you.

Fig. 271 – Achilles retreated in his tent, while a number of men take Briseis away (© Trustees of the British Museum)

He then selfishly declared he would retreat from the war and return home with his men, leaving his fellow Greeks without their best warrior. On top of this, Achilles went to the seashore, where he managed to convince his mother to ask Zeus to “help the Trojans […] corner Achaeans by the sea,” until he had his timê back.

In an attempt to solve the issue, Nestor, the wisest of the Greeks, persuaded Agamemnon to make amends with Achilles. Knowing he needed Achilles to win the war, Agamemnon agreed and was willing to give Briseis back. On top of that, he offered more slave women, the kingship of seven cities, and marriage to one of his daughters. He sent three men, Odysseus, Phoinix, and Aias (Ajax in Latin), to deliver this message to Achilles. When they arrived, they found Achilles sitting by his tent, playing his lyre and singing “klea andron” (“the glories of man”). Achilles kindly greeted his friends, stating they were “the men I love the most, even in my anger,” and offered them a meal. When informed about Agamemnon’s decision, Achilles was not impressed. He explained that the confrontation had made him lose interest in timê altogether. “If it can be taken away so easily, what is its worth?” The whole idea of collecting timê had become pointless to Achilles, and with this, his motivation to fight had disappeared:

Fate (moira) is the same for the man who holds back, the same if he fights hard. We are all held in a single honor (timê), the brave with the weaklings. A man dies still if he has nothing, as one who has done much. Nothing is won for me, now that my heart has gone through its afflictions, in forever setting my life on the hazard of battle. [106]

The first to try to change his mind was Odysseus, the cleverest of the Greeks and the best at persuasion, but he was not successful. Then came Phoinix, an old man who had cared for Achilles when he grew up. Phoinix attempted to appeal to Achilles’s emotions and his sense of duty towards his father. Both men, however, were unsuccessful at changing his mind. Finally, there was Aias, the best Greek fighter after Achilles. Aias tried to appeal to Achilles’s sense of comradeship with his fellow warriors, but he also accused Achilles of being pitiless towards them, especially after all they had done for him. Although Achilles’s anger remained, Aias’s speech made him at least decide not to return home. He also claimed he was willing to fight, but not until the Trojans reached the Greek ships and set them on fire. He was only willing to fight a defensive war.

The Trojans

Although the Trojans were the enemy, they are generally portrayed as sympathetic in the Iliad, especially compared to the aggressive Greeks. The Trojans didn’t fight for either timê or kleos. Instead, they were fighting a defensive war to protect both their city and their people. Tragically, their entire culture was on the line because of one adulterous affair.

The sympathy of the Trojans is especially clear in the role of Prince Hektor. We see him as a dedicated father, husband, and older brother. He is a noble and civilized man, well-connected to his family and willing to take responsibility to defend his community. We see this play out, for instance, in a conversation with his wife, Andromache. His wife does her best to convince him not to go to war, reminding him that Achilles had already killed her parents and her brother and that Hektor was all she had left (“Pity me. Stay here in this tower. Don’t orphan your child and make your wife a widow”). Hektor, however, pointed to his duty as protector of the city and his people and the shame he would feel if he did not face his enemies. We read:

All these things are in my mind also, lady; yet I would feel deep shame before the Trojans, and the Trojan women with trailing garments, if like a coward I were to shrink aside from the fighting; and the spirit will not let me, since I have learned to be valiant and to fight always among the foremost ranks of the Trojans, winning for my own self great glory, and for my father. [106]

Nevertheless, Hektor showed deep empathy for his wife’s predicament:

My heart and mind know well the day is coming when sacred Ilion will be destroyed. […] but what pains me most about these future sorrows is not so much the Trojans, [my mother] Hecuba, or King Priam, or even my many noble brothers, who’ll fall down in the dust, slaughtered by their enemies. My pain focuses on you, when one of the bronze-clad Achaeans leads you off in tears, ending your days of freedom [suggesting she will be dragged off into slavery].

While Hektor still had hope that Troy would prevail, we, the readers, already know that this whole list of horrors will actually come to pass. He then said goodbye to his son:

He kissed his dear son and held him in his arms. “Zeus, […] grant that this child, my son, may become, like me, pre-eminent among the Trojans, as strong and brave as me. Grant me that he may rule Troy with strength. May people someday say, as he returns from war: ‘This man is far better than his father.”

Meanwhile, in stark contrast, Achilles was raging in his tent over his lost timê, leaving his comrades to fight for themselves.

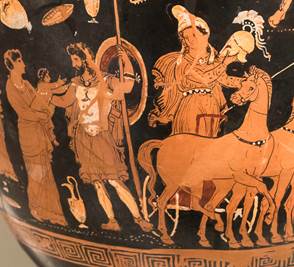

Fig. 272 – Hektor saying farewell to his wife and child (c. 340 BC) (Egisto Sani, permission; Altes Museum Berlin, Germany)

Fig. 273 – Achilles in his tent wrapped in a cloak grieving the death of Patroklos (c. 460 BC); (Jastrow; CC BY 3.0; Louvre, France)

Since Paris had caused the war, he finally agreed (after ten years) to challenge Menelaos to a one-on-one duel to the death to settle their dispute. But when he finally faced Menelaos, he got overwhelmed by fear and withdrew. Hektor finally snapped and put his brother in his place:

Despicable Paris, handsomest of men, but woman-mad seducer. How I wish you never had been born or died unmarried. […] Now long-haired Achaeans are mocking us, saying we’ve put forward as a champion one who looks good, but lacks a strong brave mind. […] You’d get no help then from your lyre, long hair, good looks—Aphrodite’s gifts—once face down, lying in the dirt. [107]

Pressured by his brother, Paris finally agreed to resume. The fight took place just outside the city walls. The old Trojan king Priam, another sympathetic Trojan, invited Helen to sit next to him to watch the fight unfold from atop the city wall. Although he knew that Helen’s affair was the cause of the war, he still treated her with sympathy. We read:

Come over here, dear child. Sit in front of me, so you can see your husband of long ago, your kinsmen and your people. I don’t blame you. I hold the gods to blame. They are the ones who brought this war upon me, devastating war against the Achaeans. [108]

Menelaos soon got the upper hand, but when he was about to kill Paris, the goddess Aphrodite “snatched [him] up” to rescue him, taking him to his bedroom behind the city walls. When Helen saw Paris, she told him she was ashamed of his loss and wished he had “died there, killed by that strong warrior who was my husband once.” Her response brought the pointlessness of the war to new depths. The Trojans were now risking everything they had over a love affair that had already ended.

The death of Patroklos

The event that finally got Achilles out of his tent was the death of Patroklos. Homer described Patroklos as Achilles’s best friend, but later Greek writers sometimes portrayed them as lovers. When Odysseus, Ajax, Agamemnon, and other Greeks were wounded on the battlefield, and the ships were burning, Patroklos entered Achilles’s tent to inform him of what had happened while “shedding warm tears.” In response, “godlike Achilles felt pity,” although he still refused to fight. He did allow Patroklos to wear his breastplate and helmet, making the soldiers on both sides think that Achilles had returned. In this way, he hoped to frighten the Trojans and encourage the Greeks. When the Trojans saw Patroklos, they became deeply afraid, believing Achilles had finally managed to set aside his menis (wrath) and turned to love (philotes) for his comrades. Achilles had told Patroklos to only drive the Trojans away from the ships and not to chase them back to Troy. Patroklos ignored this order, and when he reached the city wall, he was confronted and killed by Hektor. Hektor then stripped Achilles’s armor from his body and wore it himself, after which the Greeks and Trojans fiercely fought over Patroklos’s body.

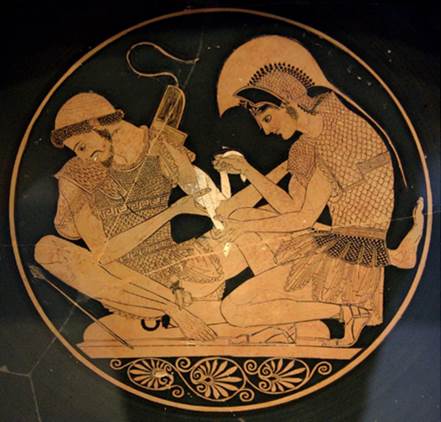

Fig. 274 – Achilles and Patroklos. (Bibi Saint-Pol; Antikensammlung Berlin, Germany)

When Achilles heard of Patroklos’s death, he was overwhelmed with grief:

A black cloud of grief swallowed up Achilles. With both hands he scooped up soot and dust and poured it on his head, covering his handsome face with dirt […]. He lay sprawling—his mighty warrior's massive body collapsed and stretched out in the dust. With his hands, he tugged at his own hair, disfiguring himself. […] Achilles’s noble heart moaned aloud. […] His noble mother heard it from the ocean depths [and] left [her] cave. [107]

His mother, Thetis, mourned with him, but also reminded him that he had gotten exactly what he wished for, for had he not begged Zeus to give the military advantage to his enemies? It was time to recognize his mistake and join his comrades who were still suffering because of it. But Achilles could only think about revenge. All he wanted was to kill Hektor:

My own heart has no desire to live on, to continue living among men, unless Hector is hit by my spear first, losing his life and paying me compensation for killing Menoetius’s son, Patroklos.

Thetis then reminded him once more that if he decided to fight, he would die soon after. Achilles finally accepted this fate, choosing death as a price for avenging Patroklos. From this moment on, Homer often described Achilles as though he was already dead. For instance, when hearing that Patroklos was killed, Achilles collapsed on the ground and lay “stretched in the dust weeping for his friend,” a sentence usually reserved for warriors fallen in battle. When Thetis mourned with him, she stood behind him with his head in her hands, a pose associated with mourning the dead. When Hektor put on Achilles’s armor, we read it was like putting on his own death. Zeus, however, was not ready to let Hektor go just yet, as he had always been a pious man. He spoke:

Ah, poor wretch! There is no thought of death in your mind now, and yet death stands close beside you as you put on the immortal armor of a surpassing man. There are others who tremble before him. Now you have killed this man’s dear friend, who was strong and gentle, and taken the armor, as you should not have done, from his shoulders and head. Still for the present I will invest you with great strength to make up for it that you will not come home out of the fighting. [106]

When the Greeks finally recaptured Patroklos’s body and brought it back to the ships, Achilles was not ready to bury it. He simply couldn’t reconcile himself with his death. To keep the body from decaying, Thetis instilled it with ambrosia—the drink of the gods. She then went to Hephaistos, the smithy of the gods, who made Achilles a new armor and a magnificent shield.

Before heading to Troy to avenge his friend, Achilles took a moment to reconcile with Agamemnon. After the death of Patroklos, his feud over Briseis had lost all meaning. All he wanted now was to kill Hektor. Agamemnon tried to persuade him to eat before the fight, but Achilles swore not to eat or drink before he had wreaked vengeance on the Trojans. When Achilles returned to the war, he unleashed his almost godlike strength. He killed without pity, even when he ought to have shown mercy. The young Trojan warrior Tros fell at his knees and clutched them, begging him to spare his life, but Achilles struck him in his liver without mercy. At one point, he even killed an unarmed man named Lycaon, another son of Priam, who too begged for mercy:

So, friend, you die also. Why all this clamor about it? Patroklos also is dead, who was better by far than you are. Do you not see what a man I am, how huge, how splendid and born of a great father, and the mother who bore me immortal? Yet even I have also my death and my strong destiny, and there shall be a dawn or an afternoon or a noontime when some man in the fighting will take the life from me also either with a spear cast or an arrow flown from the bowstring. [106]

Naturally, we can understand Achilles’s anger over the death of his friend, but we have to keep in mind that he had also killed many of Hektor’s brothers. The loving Achilles of the past had given way to a man blinded by hatred.

Fig. 275 – Hephaistos presents the new armor to Thetis (Bibi Saint-Pol; Antikensammlung Berlin, Germany)

Achilles versus Hektor

Before going to the battlefield, Hektor met with his father. King Priam begged him not to face Achilles, but Hektor felt ashamed to back down from a fight in front of the entire city of Troy. When he finally met Achilles, Hektor was overwhelmed by fear and ran away. Achilles pursued him until they ended up at a spring where the Trojan women used to wash their clothes. The place gives a glimpse of what Trojan life was like “before the sons of the Achaeans came to Troy,” further adding to the tragedy of Troy’s fated destruction.

Zeus then weighed

the fate of Hektor and Achilles on a golden scale. Hektor’s fate went down,

signifying it was time for him to die. Athena then transformed into one of

Hektor’s friends and persuaded him to stop and take on Achilles together.

Hektor agreed, but when he called on his friend for support, he was nowhere to

be seen. Before the fight started, Hektor asked Achilles to return his body to

his parents in case he died so he could get the burial needed for his psyche to

go to the underworld. Achilles blatantly refused, in crude violation of the

warrior’s code. Instead, he told Hektor he would throw his body to the dogs.

After a brief duel, first throwing ![]()

![]()

spears and then a sword fight, Achilles

stabbed Hektor in the neck. Just before his death, Hektor begged Achilles once

more to return his body to his parents, instead of leaving his body for the

dogs. Achilles’s response was brutal:

No more begging, you dog, by knees or parents. I wish only that my spirit and fury would drive me to hack your meat away and eat it raw for the things that you have done to me. So there is no one who can hold the dogs off from your head. [106]

Hektors “life slipped out, flying off to Hades,” after which Achilles did the unthinkable. He attached Hektor’s body to his chariot and dragged him around the city while his wife and parents watched from atop the city wall. Hektor’s wife fainted at the sight.

Priam’s plea

Achilles had his revenge, but it did not bring him relief, and he still wasn’t able to bury his friend. This changed when Patroklos’s ghost appeared, asking Achilles to bury him so he could go to the underworld. This finally convinced Achilles. For the occasion, he killed twelve Trojan youths as a sacrifice and dragged Hektor’s body around his tomb, but it still didn’t ease his heart. He also still refused to eat, to the point where the goddess Athena had to keep him alive by instilling his chest with ambrosia. Thetis had done the same to the body of Patroklos, again associating Achilles with death.

Finally, the gods couldn’t stand Achilles’s behavior any longer. Apollo addressed the gods in a divine council, telling them that Achilles had become a shameless and destructive force without mercy. Apollo also concluded it was time Hektor’s body was returned to his family, especially since Hektor had always been a pious man who had sacrificed to the gods. Thetis was sent to convince Achilles to return the body. When his mother spoke to him, he reluctantly accepted. At the same time, the goddess Iris was sent to urge Priam to visit Achilles in his tent. The god Hermes helped him get there safely. He then entered Achilles’s tent and asked Achilles to pity him and to return Hektor’s body. He told Achilles he had been a very fortunate man before the Greeks came to Troy, but now his son was dead. Hoping for mercy, he then “clasped [Achilles’s] knees and kissed his hands, those dreadful hands, man-killers, which had slain so many of his sons.” Achilles reacted in shock and “looked on godlike Priam in astonishment,” after which Priam spoke the following painful but beautiful words:

Honor then the gods, Achilles, and take pity upon me remembering your father, yet I am still more pitiful; I have gone through what no other mortal on earth has gone through; I put my lips to the hands of the man who has killed my children. [106]

Achilles reacted with wonder, compassion, and grief and agreed to return the body. The two men then wept over their losses, after which Achilles comforted Priam by reminding him of the mixed good and evil that Zeus bestowed on every human life.

Despite their moment of compassion, Achilles also reminded Priam that they were still enemies. Achilles ordered his slave women to wash Hektor’s body as best as they could to mask the damage that he had done. He did this to ensure that Priam would not get angry, as it might, in turn, lead Achilles to act out. Achilles then carried Hektor’s body to Priam’s wagon.

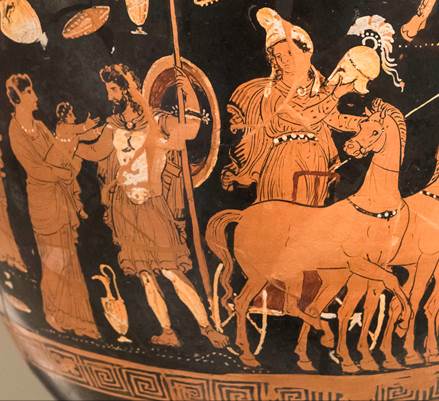

Fig. 277 – Achilles dragging the corpse of Hektor behind his cart. Priam and Andromache are standing on the left. The ghost of Patroklos is depicted on the top right (© Boston Museum of Fine Arts, United States)

Fig. 278 – A hydria depicting the ransom of Hector. Priam visits Achilles to return his dead son Hektor (© Harvard Art Museum, United States)

Through the encounter with Priam, Achilles had regained his humanity, recovering his loving heart. He told Priam it was time to eat, and he served him a meal. He also promised a truce of eleven days to give the Trojans time for a proper funeral. The Iliad ends with Andromache’s and Helen’s lament over Hektor’s body. Helen remarked how well Hektor had always treated her, despite all that had happened. Then his body was placed on the funeral pyre, after which his ashes were collected and buried in an urn. The last line of the epic reads:

So they buried Hektor, tamer of horses. [106]

The Trojan Horse

The Iliad and the Odyssey are just two of eight books covering the Trojan War. The other books have since been lost, although summaries have been found. Luckily, the Greeks regarded the Iliad and the Odyssey as the best parts. A work preceding the Iliad described events leading up to the war and the first nine years of the conflict. After the Iliad, the story continued in another four lost volumes. Paris took revenge on Achilles for killing his brother by shooting him in the heel with a poisonous arrow, leading to his death. To defeat the Trojans, Odysseus devised a clever trick. He built a wooden horse, the Trojan Horse, which the Greeks offered as a gift of peace to the Trojans. The Trojans accepted the gift but did not know that several Greek men were hiding inside. Once inside the city walls, they waited until it was dark, and then they attacked ruthlessly, sacking the city.

The Odyssey

During their attack, the Greeks committed horrible war crimes. Neoptolemus, son of Achilles, killed Priam on the altar of Zeus, where he had taken refuge. Andromache was taken into slavery, and Odysseus threw Hektor’s baby from the city walls. These war crimes angered the gods, for which the Greeks were heavily punished. This is where Homer’s second epic, the Odyssey, starts off. Being cursed for his misdeeds, it took Odysseus ten years of wandering at sea, meeting strange mythological creatures, until he was finally reunited with his wife back home in Ithaca. His homecoming (nostos) is the main theme of the book. The Odyssey starts as follows:

Tell me, Muse, of the man of many turns [clever ideas], who was driven far and wide after he had sacked the sacred city of Troy. Many were the men whose cities he saw, and learnt their minds, many the sufferings on the open sea he endured in his heart, struggling for his own life and his companions’ homecoming [nostos]. [109]

Fig. 279 – The Mykonos vase, depicting Greek warriors hidden inside the Trojan horse (c. 670 BC) (Travelling Runes, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The story starts in the middle of Odysseus’s journey home. He was held in a cave by the beautiful nymph Calypso, who wanted Odysseus for a husband, while Odysseus instead dreamt of going back to his earthly wife Penelope. Zeus had mercy on Odysseus, thinking he had suffered enough, but Poseidon, the god of the sea, was furious at him for blinding his son, a one-eyed giant called a cyclops. Zeus decided to ignore Poseidon and sent Hermes to demand that Calypso release him. Meanwhile in his home in Ithaca, a group of suitors competed for his wife under the assumption that Odysseus had died. With Odysseus out of the picture, they regularly organized feasts in his house, eating his food and drinking his wine.

Odysseus left Calypso’s island by boat, but when Poseidon saw him, he “drove the clouds together, seized his trident, and stirred up the sea,” after which Odysseus washed ashore on an island, where he was asked by its inhabitants to tell his story. Among his many adventures, he chanced upon the island of the Lotus Eaters, who offered lotus plants which made any man who ate them forget about wanting to go home. Just in time, Odysseus forced his men back on his ship and left. Next, he reached the country of the Cyclops. They snuck into one of their caves to steal some sheep, but before they could leave, a cyclops had returned and closed the cave with a massive rock. The giant ate a few of Odysseus’s men, but then they devised a plan. They turned the cyclops’s giant club into a pointy spear and jammed it into his eye. They then escaped by hanging under the bellies of his sheep. Next, he reached an island where a man called Aeolus, keeper of winds, created a wind to blow his ships home. To not be blown off course, he put the other winds in a bag which he gave to Odysseus. Yet, when they were almost home, his men began to believe that Odysseus was hiding gold in this bag. When they opened it, the other winds were released and the ships were pushed back to Aeolus’s island. Next, he reached an island of the goddess Circe, who drugged some of his men, and then turned them into pigs with her magic wand. Odysseus heard what had happened and arranged for Hermes to give him a drug to prevent her magic from working. When Circe realized her tricks did not work on him, he managed to win her over as his lover. After a while, Odysseus told her that he had to leave and continue his journey, which she reluctantly agreed to. Circe advised him to go to the underworld to consult the blind prophet Teiresias. Sailing to the edge of the world, he dug a hole to the underworld, sacrificed a ram, after which the shadows of the dead appeared. Among the shadows was his dead mother, who had still been alive when he set off for Troy. Seeing her brought tears to his eyes. She said she died out of grief, hoping for the return of her son. Then Teiresias appeared, who told him he would meet the flocks of the sun god Helios and that he had to prepare for trouble at home. Achilles also made his appearance, as we have quoted earlier in the chapter. Having all the information he needed, he sailed off. On his way, he met the sirens, “sitting in a meadow, surrounded by a pile, a massive heap, of rotting human bones encased in shriveled skin.” [110] Circe had advised Odysseus and his crew to sail past them with wax in their ears, since their singing would hypnotize any man. Odysseus, curious about their voices, had his men tie him to his mast, telling them not to untie him no matter what happened (see Fig. 280).

He next reached the island where the cattle of Helios grazed. Circe had told Odysseus not to harm the sheep, but eventually his men got hungry and ate them. When they returned to sea, Helios convinced Zeus to send a thunderstorm, causing his entire crew to die. Only Odysseus survived, washing ashore on Calypso’s island with the help of the gods.

Fig. 280 – Odysseus tied to the mast of his ship surrounded by sirens. Homer did not describe what the sirens look like, but usually they are depicted as half human and half bird (c. 475 BC) (ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

After telling his story, the islanders decided to help him return home. Once there, Athena transformed him into an old beggar, allowing him to enter his house in disguise. After teaming up with his son Telemachus, they (brutally) killed the suitors who had been ravaging his house (and even the women who had slept with them). Then, Odysseus finally reunited with his faithful wife Penelope.