In Roman-ruled Israel, a Jewish carpenter’s son named Jesus claimed to be the son of God and preached to his fellow men to prepare for the end of time. Jesus was persecuted for his beliefs, which, in the end, led to his unjust conviction and crucifixion. According to Christianity, Jesus did not use his divine powers to save himself, but instead willingly sacrificed his life, thereby relieving mankind of its sins.

Jesus was also a great reformer, rejecting the old tribal passages from the Old Testament while embracing its gems. When asked about the most important lessons from the Old Testament, he said “love God” and “love your neighbor as yourself.” He taught his disciples about unconditional love and forgiveness, and instructed them to care for the poor and the unfortunate.

The Messiah

Around the time of Jesus (c. 4 BC–30 AD), various Jewish communities were expecting the coming of the apocalypse. They believed the world was dominated by the forces of evil, but soon God would overthrow them and install the kingdom of God here on earth. Crucial for the success of this plan was the prophesied Messiah (the “anointed”), who was chosen by God to lead and save the world.

The idea of a coming “Messiah” had a long history. During the reign of King David, God had promised that his descendants would always be on the throne, but not long after his death, Israel came under the control of various foreign powers. Trying to make sense of the prophecy, various prophets began to predict that at least a descendant from his line would return to the throne. This figure is today often called the Davidic Messiah. The prophet Micah (8th century BC), for instance, spoke of a king from Bethlehem, the birthplace of David, who would free Israel from Assyria. Similarly, the prophet Jeremiah (c. 650–570 BC) claimed “the days are coming” that God will “raise up from David’s line a righteous branch.”

Over time, the Messiah morphed from a “regular” king to a more supernatural figure. In a famous vision from the Book of Daniel (2nd century BC), Daniel saw a “Son of Man” who came down with the clouds to rule the world for eternity:

In my vision at night I looked, and there before me was one like a Son of Man, coming with the clouds of heaven. He approached the Ancient of Days and was led into his presence. He was given authority, glory and sovereign power; all nations and peoples of every language worshiped him. His dominion is an everlasting dominion that will not pass away, and his kingdom is one that will never be destroyed. [50]

In 1 Enoch (1st century BC), a work not included in the Bible, this Son of Man became a figure who had existed before creation and who would speak judgment over the dead.

In the New Testament, various of these attributes were combined in the figure of Jesus. He is called the Messiah (which in Greek translates into “Christos”), and also the Son of Man, and the son of David. Reminiscent of The Book of Daniel, we read in the New Testament:

But in those days, following that distress, the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light; the stars will fall from the sky, and the heavenly bodies will be shaken. At that time, people will see the Son of Man coming in clouds with great power and glory. And he will send his angels and gather his elect from the four winds, from the ends of the earth to the ends of the heavens.

Besides the Messiah, there was also another figure in the Old Testament, whom the second Isaiah (6th century BC) called the Servant of the Lord. Cryptically, we are told that the Lord “wanted to crush” this figure and “cause [him] to suffer” so that his life would become “an offering for sin.” The Servant of the Lord, we are told, was horrifying to look at and would be treated with contempt:

Surely, he took up our pain and bore our suffering, yet we considered him punished by God, stricken by him, and afflicted. But he was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was on him, and by his wounds we are healed.

Christians have often taken this verse as a prophecy of the suffering and redemption of Jesus, yet this character is not referred to as the “Messiah” in the Old Testament. In fact, Jewish texts consistently regard the Messiah as a powerful ruler and not as a suffering victim. A close read reveals that the suffering Servant of the Lord is Israel herself. We know this because the text states: “You are my servant, Israel, in whom I will be glorified.” Another clue is that the suffering is described in the past tense (and therefore cannot be a prediction of the coming of Jesus), while only the redemption is written in the future tense as a prediction of things to come.

Yet there are some clear similarities between Jesus and the Servant of the Lord, as both would take upon themselves the suffering of the world:

For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.

The soul and resurrection

Curiously, the Jews of the Old Testament barely believed in a soul or an afterlife. They only knew of a place called Sheol, where the dead existed as shades, irrespective of their moral deeds. Having lost their body, these shades were barely human, without personality or memories. In the first centuries BC, likely influenced by their Greek overlords, some Jewish communities began to adopt the idea of an eternal soul, which to some extent could function independently of the human body and retained its memory and personality. With this adoption, the physical body simply became the soul’s temporary earthly vessel. We see this transition, for instance, in the Septuagint (3rd century BC), the first translation of the Old Testament into Greek. Here, the word “nefesh,” meaning “life force,” was translated into “psuche,” meaning “soul.” The fusion of Jewish and Greek thought can be seen more explicitly in the work of Philo (c. 20 BC–50 AD), a Hellenized Jew, who was one of the first to read the Bible allegorically. In his view, the more abstract creation story in Genesis I referred to the creation of Plato’s world of Forms, while the version in Genesis II referred to the creation of the material world based on these Forms.

The ideas of an afterlife in either heaven or hell likely came from the Zoroastrians in Persia. Their prophet Zarathustra likely lived somewhere between 1200 and 1000 BC. He believed that the universe was a battle ground for the forces of good and evil. In the centuries after his death, his beliefs were greatly embellished. It came to be believed that after death, the soul of a good person would pass to heaven, while the soul of a wicked person would be tortured in hell. On a more cosmic scale, it was believed that the forces of good and evil would clash in a final battle, leading to a definitive victory of the good. At that time, a figure known as the Saoshyant would also bring about a resurrection of the dead, after which the wicked will pass through a river of molten metal burning away all their sins. Interestingly, Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian communities would insist on a physical resurrection, still lacking the belief that a soul could be truly functional without a body.

The first definitive Judaic reference to the resurrection comes from the 3rd century BC, in The Book of Enoch, which did not become part of the Bible. In this book we read how the patriarch Enoch was taken on a journey with angels. The angels showed him a mountain with four recesses in which the dead waited for their judgment. Three recesses were dark, housing evil souls, while one was light, for the just souls. At a later point, we read, the good souls will eat from the Tree of Life and will regain their earthly body.

The Book of Daniel and 2 Maccabees, both from the 2nd century BC, also mention the resurrection. Both texts were written during a time when the Jews were persecuted by their Greek overlords, and therefore give extra attention to martyrdom. In Daniel, we read that martyrs will wake up from the dead and live forever, while apostates will be punished. In 2 Maccabees, a martyr yelled out to his torturer “at his last breath”:

You accursed wretch, you dismiss us from this present life, but the King of the universe will raise us up to a renewal of everlasting life, because we have died for his laws.

We find similar ideas among the Jewish communities that were influential at the time of Christ. The Pharisees, the most influential group, believed that the good would be rewarded with a new body, while the wicked would be punished for all eternity. According to the New Testament, they also believed in angels, ghosts, immortal souls, and the Last Judgment, when God would decide definitively who would end up in heaven and who in hell. In contrast, the Sadducees, the second most influential Jewish branch, believed life simply ended after death.

Similarly, Jesus also believed in heaven and hell, the Last Judgment, and the resurrection, which according to Jesus would occur within his generation:

Truly I tell you, this generation will certainly not pass away until all these things have happened. Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words will never pass away. [50]

Despite his usually tolerant message, we read that Jesus had come to Earth to perform the Last Judgment, separating the righteous from the evildoers:

Fig. 342 – Last Judgment by Stefan Lochner ( c. 1435 AD) (Wallraf–Richartz Museum, Germany)

When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, he will sit on his glorious throne. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate the people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. He will put the sheep on his right and the goats on his left. Then the king will say to those on his right, “Come, you who are blessed by my Father; take your inheritance, the kingdom prepared for you since the creation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.” Then, the righteous will answer him, “Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you something to drink? When did we see you a stranger and invite you in, or needing clothes and clothe you? When did we see you sick or in prison and go to visit you?” The King will reply, “Truly, I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.”

Then he will say to those on his left, “Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels. For I was hungry and you gave me nothing to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not invite me in, I needed clothes and you did not clothe me, I was sick and in prison and you did not look after me.” They will also answer, “Lord, when did we see you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or needing clothes or sick or in prison, and did not help you?” He will reply, “Truly I tell you, whatever you did not do for one of the least of these, you did not do for me.” Then they will go away to eternal punishment, but the righteous to eternal life. [50]

The religion of the poor

As discussed, most Jews expected the Messiah to be a mortal king, who through great strength would reconquer Israel from the Romans and would then restore the Davidic throne, establishing God’s kingdom on earth. Interestingly, Jesus did not meet these criteria at all. Instead of a triumphant warrior-king, he would be reviled, betrayed arrested, and crucified as a criminal. Paradoxically, this became one of the most appealing selling points of Christianity, as it gave solace to all those followers who had experienced tremendous hurt in life. Knowing that the Son of God went through so much pain, it eased their own burden.

Jesus made it no secret that his disciples could expect a similar treatment at the hands of man:

On one occasion, he warned an overly optimistic follower about the heaviness of the burden of discipleship:

As they were walking along the road, someone said to Jesus, “I will follow you wherever you go.” Jesus replied, “Foxes have dens and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has no place to lay his head.”

The next famous passage contains the same warning:

Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law; and one’s foes will be members of one’s own household. Whoever loves their father or mother more than me is not worthy of me; and whoever loves their son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me; and whoever does not take up the cross and follow me is not worthy of me. Those who find their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it. [162]

Jesus’s message also was completely contrary to what was expected of a Davidic warrior-king. Instead of demanding authority, Jesus promoted the virtue of humility and voluntarily chose to associate himself with the poor, the unfortunate, and the outcasts. Jesus even sat and ate with sinners. The following verse explains this choice:

It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners. [50]

His choice to side with the downtrodden, who were usually neglected by all, also eased the suffering of many Christians throughout the ages. In the Gospel of Matthew, we famously read:

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth. Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled. Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God. Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God. Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are you when people insult you, persecute you and falsely say all kinds of evil against you because of me. Rejoice and be glad, because great is your reward in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

In some ways, Jesus claimed, the poor had an even higher chance of salvation than the rich. We read:

Jesus looked around and said to his disciples, “How hard it is for the rich to enter the kingdom of God!” The disciples were amazed at his words. But Jesus said again, “Children, how hard it is to enter the kingdom of God! It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God.”

Jesus taught that instead of judging others, it is wiser to look at oneself first:

Do not judge, or you too will be judged. For in the same way you judge others, you will be judged, and with the measure you use, it will be measured to you. Why do you look at the speck of sawdust in your brother’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your own eye? [...] You hypocrite, first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother’s eye.

Instead, Jesus encouraged forgiveness (“Forgive, and you will be forgiven”). This tolerance, he believed, should even be extended to one’s enemies:

But to you who are listening, I say: Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you. If someone slaps you on one cheek, turn to them the other also. If someone takes your coat, do not withhold your shirt from them. Give to everyone who asks you, and if anyone takes what belongs to you, do not demand it back. Do to others as you would have them do to you.

Similarly:

You have heard that it was said, “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” But I say to you, do not resist an evildoer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also; and if anyone wants to sue you and take your coat, give your cloak as well.

And:

You have heard that it was said, “Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.” But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven.

Paul

The oldest books of the New Testament were written by an educated Jewish man named Paul (c. 5–c. 67 AD). Paul had been a persecutor of early Christians, but when the resurrected Jesus appeared before him, he converted to Christianity. Paul became the man most responsible for spreading the faith throughout the Roman world, bringing his message to both Jews and Gentiles, men and women, free men and slaves. Whereas the Jews generally considered themselves the chosen people—the only tribe on earth to get special treatment from God—Paul presented Christianity as a world religion that was open to all:

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

During the early days of Christianity, this was put into practice. While hierarchical differences continued to exist in the outside world, within the church community, all Christians were brothers with equal rank, since all were sons and daughters of God. Unheard of in much of the Roman world, women, and even slaves, took up leadership positions in the early church, although this became less common after the 1st century AD.

Like Jesus himself, Paul was also a strong believer in the end-time, which he expected to arrive at any moment:

In the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet […] the dead will be raised […] We who are alive, who are left, will be caught up in the clouds together with [the resurrected dead] to meet the Lord in the air; and so we will be with the Lord forever.

Paul wrote letters to Christian communities across the Roman Empire to instruct them on matters of faith. These letters are included in the Bible. In one of the most celebrated passages, Paul encouraged humility in the expression of faith. While some would show off their religiosity by “speaking in tongues,” disrupting the prayers of others, Paul instead insisted on the importance of love (agape):

If I speak in the tongues of men or of angels, but do not have love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give all I possess to the poor and give over my body to hardship that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing.

Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.

Surprisingly, Paul’s letters show almost no knowledge of the biographical stories usually associated with Jesus, except for his crucifixion and resurrection. In his view, Jesus’s death was not an accident, but was God’s plan. God had sent his own son to die on the cross to absolve the sins of mankind.

According to Paul, all people have sinned in some way or another. Therefore, according to Mosaic Law, everyone should be condemned. As a result, Paul considered Mosaic Law insufficient to solve the problem of sin. He thus rejected it in favor of faith in Jesus as the only way to salvation:

Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law [...] so that we might receive the promise of the Spirit. [50]

Paul also connected Jesus’s death to the fall of Adam and Eve, closing the arc of history from creation to redemption. While Adam and Eve had brought sin and death into the world, this state of corruption was finally restored when God sacrificed his own son for the sins of mankind:

For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive.

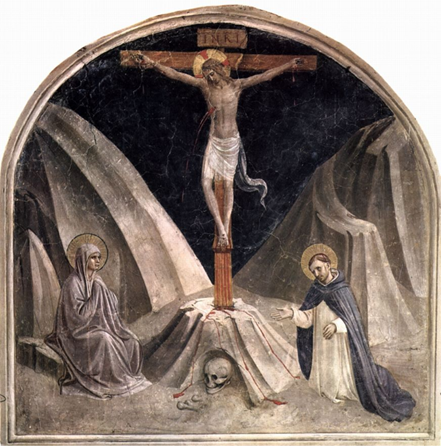

In later art, this connection between fall and redemption was pushed even further. The Tree of Good and Evil from the Garden of Eden became associated with the cross, and the site of Jesus’s crucifixion—known as Golgotha or “Place of the Skull”—became associated with the burial place of Adam’s skull (see Fig. 343).

Fig. 343 – The crucifixion with Adam’s skull by Fra Angelico (15th century) (Museo di San Marco, Italy)

In one passage, Paul described Jesus not as the Son of God, but as equal to God:

Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross. [162]

Strangely, the equation of God with Jesus is not expounded upon by Paul and does not appear in the earliest Gospels. This leads some scholars to believe that Paul is here speaking metaphorically, referring instead to Jesus’s divine nature as the Son of God.

The Gospels

The first four books of the New Testament are the Gospels, which are biographies describing the life and teachings of Jesus. Although the documents are anonymous, they became associated with the disciples Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John since the second century AD. It is very likely, however, that they weren’t the actual authors. The texts describe them as uneducated peasants, while the Gospels are clearly written by educated men. On top of this, these disciples did not speak Greek, the language in which the Gospels were written, and the texts were also written in the third person and contain no direct references to the author’s own involvement with Jesus.

The oldest Gospel, the Gospel of Mark, was written about 20 years after Jesus’s death, around 65–70 AD. Next comes the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke (80–85 AD), who both drew from Mark and from an unknown source called Q by modern historians. Finally, the Gospel of John was written about 90–95 AD.

Although the Gospels show much overlap in content, there are also many clear inconsistencies between them. Interestingly, these inconsistencies reveal the evolution of early Christian ideas. We will trace this development in the following sections.

The Gospel of Mark

In the first line of the Gospel of Mark, the text claims to bring “good news” (“gospel”) about “Jesus Christ, the Son of God.” Mark skips the birth and upbringing of Jesus and jumps straight to John the Baptist, who was himself an apocalyptic Jewish prophet. As he is also mentioned by the Jewish historian Josephus (c. 37–100 AD), he was likely a real historical character. We are told John was an ascetic, who wore a rough cloak of camel hair and lived on locusts and wild honey. People flocked to him to confess their sins and be forgiven through baptism. Jesus was one of these people:

At that time Jesus came from Nazareth in Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan. Just as Jesus was coming up out of the water, he saw heaven being torn open and the Spirit descending on him like a dove. And a voice came from heaven: “You are my son, whom I love; with you, I am well pleased.” [50]

John then prophesied that someone more powerful than himself would come after him. He said:

I baptize you with water, but he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit.

Right after, we read that Jesus was tempted by Satan:

The Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness. And he was in the wilderness forty days, tempted by Satan; and he was with the wild beasts; and the angels ministered to him. [162]

The Gospel of Luke tells us more about what happened:

The devil said to him, “If you are the son of God, command this stone to become bread.” And Jesus answered him, “It is written, ‘Man shall not live by bread alone.’’’ [Deuteronomy 8:3] [in Matthew, the line is extended with “but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God.”]

The devil led him up to a high place and showed him in an instant all the kingdoms of the world. And he said to him, “I will give you all their authority and splendor; it has been given to me, and I can give it to anyone I want to. If you worship me, it will all be yours.” Jesus answered, “It is written: ‘Worship the Lord your God and serve Him only.’’’ [Deuteronomy 6:13]

The devil led him to Jerusalem and had him stand on the highest point of the temple. “If you are the Son of God,” he said, “throw yourself down from here. For it is written: ‘He will command his angels concerning you to guard you carefully; they will lift you up in their hands, so that you will not strike your foot against a stone.’’ Jesus answered, “It is said: ‘You shall not tempt the Lord your God.’’’ [Deuteronomy 6:16]

When the devil had finished all this tempting, he left him until an opportune time. [50]

Fig. 344 – Carving from the Domitilla Catacombs. The fish became an important early Christian symbol, as Jesus called his disciples “fishers of men.”

After this ordeal, Jesus acquired a number of disciples:

As Jesus walked beside the Sea of Galilee, he saw Simon and his brother Andrew casting a net into the lake, for they were fishermen. “Come, follow me,” Jesus said, “and I will make you fishers of men.” At once, they left their nets and followed him. When he had gone a little farther, he saw James, son of Zebedee, and his brother John in a boat, preparing their nets. Without delay, he called them, and they left their father Zebedee in the boat with the hired men and followed him.

We are then told that Jesus preached in a synagogue. To the surprise of the congregation, he spoke not as an expert on the Bible, but as someone who knew the mind of God firsthand. After his speech, Jesus performed various miracles, such as healing the sick and casting out demons. One of the demons recognized Jesus as the Son of God:

Just then a man in their synagogue who was possessed by an impure spirit cried out, “What do you want with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are—the Holy One of God!”

“Be quiet!” said Jesus sternly. “Come out of him!” The impure spirit shook the man violently and came out of him with a shriek.

The people were all so amazed that they asked each other, “What is this? A new teaching—and with authority! He even gives orders to impure spirits and they obey him.” News about him spread quickly over the whole region of Galilee. [50]

While the demon recognized Jesus as the Son of God, this is not true for most of the human characters in the story. It is one of the central themes in Mark that almost everyone misunderstood who he was. His family and the people in his hometown thought he had gone crazy. The Jewish leaders in the synagogue accused him of using satanic powers. Even his own disciples were not aware of his true nature, even though he performed miracles right in front of their eyes. At some point, Jesus found his disciples worrying about not having enough food on a boat trip, though he had just multiplied loaves of bread to feed thousands of people. He asked them:

How is it that you do not understand? [25]

Likewise, the disciples were shocked to see Jesus walk on water, “for they considered not [the miracle] of the loaves, for their heart was hardened.”

Halfway through the story, Jesus directly asked his disciples who they thought the Son of Man was. Only Peter answered correctly:

They replied, “Some say John the Baptist; others say Elijah; and still others, Jeremiah or one of the prophets.” “But what about you?” he asked. “Who do you say I am?” Simon Peter answered, “You are the Messiah, the son of the living God.” Jesus replied, “Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah, for this was not revealed to you by flesh and blood, but by my Father in heaven. And I tell you that you are Peter [meaning “rock”], and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven.” [50]

For reasons unknown, Jesus then asked his disciples to keep his identity as the Messiah a secret. He then added some horrifying news—he told them his fate was to suffer and die:

He then began to teach them that the Son of Man must suffer many things and be rejected by the elders, the chief priests and the teachers of the law, and that he must be killed and after three days rise again.[9] [50].

But again, the disciples did not get the message. In fact, just a few minutes after, we find them discussing who among them would be the most powerful in God’s kingdom on earth. They still didn’t seem to realize that Jesus was not going to overthrow the Romans, but was instead going to be killed by them.

Reaching Jerusalem, Jesus went to the Temple of God and found its forecourt filled with sellers of sacrificial animals and moneychangers (who exchanged Roman coins depicting the emperor, which were not allowed in the temple). Shocked by all these commercial activities in a place of worship, he overturned their tables and chased the merchants out:

Is it not written: “My house will be called a house of prayer for all nations?” But you have made it a den of robbers.’’ [Or in John: “Stop turning my father’s house into a market!”]

Fig. 345 – The Last Supper, by Leonardo da Vinci (1495 AD) (Santa Maria delle Grazie, Italy)

Then the disciples joined Jesus for his Last Supper, where he explained his fate in more detail. During this meal, Jesus also shared bread and wine with his disciples, which he likened to his own body and blood. This act would become an important rite in Christianity known as the Eucharist:

And when it was evening, he came with the twelve. And as they were reclining at the table and eating, Jesus said, “Truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me, one who is eating with me.” They began to be sorrowful and to say to him one after another, “Is it I?” He said to them, “It is one of the twelve, one who is dipping bread into the dish with me. For the Son of Man goes as it is written of him, but woe to that man by whom the Son of Man is betrayed! It would have been better for that man if he had not been born.”

And as they were eating, he took bread, and after blessing it, broke it, and gave it to them, and said, “Take; this is my body.” And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, and they all drank of it. And he said to them, “This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many. Truly, I say to you, I will not drink again of the fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new in the kingdom of God.”

And when they had sung a hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives. And Jesus said to them, “You will all fall away, for it is written, ‘I will strike the shepherd, and the sheep will be scattered.’ But after I am raised up, I will go before you to Galilee.” Peter said to him, “Even though they all fall away, I will not.” And Jesus said to him, “Truly, I tell you, this very night, before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me three times.” But he said emphatically, “If I must die with you, I will not deny you.” And they all said the same. [162]

From this point on in Mark, the story of Jesus is one of betrayal, mockery, torture, and death. As the story progresses, we find Jesus unsure, distraught, betrayed, and abandoned (this in great contrast to the Gospel of Luke, as we shall later read). At one point, even Jesus, the Son of God, felt the need to pray to God to remove his fate from him:

They went to a place called Gethsemane, and Jesus said to his disciples, “Sit here while I pray.” He took Peter, James, and John along with him, and he began to be deeply distressed and troubled. “My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death,” he said to them. “Stay here and keep watch.” Going a little farther, he fell to the ground and prayed that if possible the hour might pass from him. “Father,” he said, “everything is possible for you. Take this cup from me. Yet not what I will, but what you will [immediately subordinating his request to the will of God].’’ [50]

Fig. 346 – The Kiss of Judas, by Giotto (c. 1305 AD) (Scrovegni Chapel, Italy)

Then we find out that it was Judas Iscariot who had betrayed the Messiah. He colluded with the Jewish leaders to have him arrested:

Judas came, one of the twelve, and with him a crowd with swords and clubs, from the chief priests and the scribes and the elders. Now the betrayer had given them a sign, saying, “The one I will kiss is the man [the kiss of Judas]. Seize him and lead him away under guard.” And when he came, he went up to him at once and said, “Rabbi!” And he kissed him. And they laid hands on him and seized him.

The Jewish high priest Caiaphas wanted Jesus condemned to death, but needed a valid accusation that would hold in Roman court. He eventually managed to pin him down as a blasphemer. Jesus, from this point in the story onward, mostly endured his accusation and death sentence in silence (in great contrast with Luke):

And they led Jesus to the high priest. And all the chief priests and the elders and the scribes came together. And Peter had followed him at a distance, right into the courtyard of the high priest. And he was sitting with the guards and warming himself at the fire. Now the chief priests and the whole council were seeking testimony against Jesus to put him to death, but they found none. For many bore false witness against him, but their testimony did not agree. And some stood up and bore false witness against him, saying, “We heard him say, ‘I will destroy this temple that is made with hands, and in three days I will build another, not made with hands.’” Yet, even about this, their testimony did not agree. And the high priest stood up in the midst and asked Jesus, “Have you no answer to make? What is it that these men testify against you?” But he remained silent and made no answer. Again the high priest asked him, “Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed?” And Jesus said, “I am, and you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power, and coming with the clouds of heaven.” And the high priest tore his garments and said, “What further witnesses do we need? You have heard his blasphemy. What is your decision?” And they all condemned him as deserving death. And some began to spit on him and to cover his face and to strike him, saying to him, “Prophesy!” And the guards received him with blows.

And as Peter was below in the courtyard, one of the servant girls of the high priest came, and seeing Peter warming himself, she looked at him and said, “You also were with the Nazarene, Jesus.” But he denied it, saying, “I neither know nor understand what you mean.” And he went out into the gateway and the rooster crowed. And the servant girl saw him and began again to say to the bystanders, “This man is one of them.” But again, he denied it. And after a little while, the bystanders again said to Peter, “Certainly, you are one of them, for you are a Galilean.” But he began to invoke a curse on himself and to swear, “I do not know this man of whom you speak.” And immediately the rooster crowed a second time. And Peter remembered how Jesus had said to him, “Before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me three times.” And he broke down and wept. [162]

Then Jesus was put on trial before the Roman governor Pilate:

‘‘Are you the king of the Jews?’ asked Pilate. “You have said so,” Jesus replied. The chief priests accused him of many things. So, again Pilate asked him, “Aren’t you going to answer? See how many things they are accusing you of.” But Jesus still made no reply, and Pilate was amazed.

Now, at the feast, he used to release for them one prisoner for whom they asked. And among the rebels in prison, who had committed murder in the insurrection, there was a man called Barabbas. And the crowd came up and began to ask Pilate to do as he usually did for them. And he answered them, saying, “Do you want me to release for you the king of the Jews?” For he perceived that it was out of envy that the chief priests had delivered him up. But the chief priests stirred up the crowd to have him release for them Barabbas instead. And Pilate again said to them, “Then what shall I do with the man you call the king of the Jews?” And they cried out again, “Crucify him.” And Pilate said to them, “Why? What evil has he done?” But they shouted all the more, “Crucify him.” So Pilate, wishing to satisfy the crowd, released for them Barabbas, and having scourged Jesus, he delivered him to be crucified.

And the soldiers led him away inside the palace, and they called together the whole battalion. And they clothed him in a purple cloak, and twisting together a crown of thorns, they put it on him. And they began to salute him, “Hail, king of the Jews!” And they were striking his head with a reed and spitting on him and kneeling down in homage to him. And when they had mocked him, they stripped him of the purple cloak and put his own clothes on him. And they led him out to crucify him.

And they compelled a passerby, Simon of Cyrene, who was coming in from the country, the father of Alexander and Rufus, to carry his cross. And they brought him to the place called Golgotha. And they offered him wine mixed with myrrh, but he did not take it. And they crucified him and divided his garments among them, casting lots for them, to decide what each should take. And it was the third hour when they crucified him. And the inscription of the charge against him read, “The king of the Jews.” And with him, they crucified two robbers, one on his right and one on his left. And those who passed by derided him, wagging their heads and saying, “Aha! You who would destroy the temple and rebuild it in three days, save yourself, and come down from the cross!” So also the chief priests with the scribes mocked him to one another, saying, “He saved others; he cannot save himself. Let the Christ, the king of Israel, come down now from the cross that we may see and believe.” Those who were crucified with him also reviled him. [50]

Not having said a word for a long period, after all the rejection and pain, after being mocked and betrayed, he finally cried out his last words in despair:

My God, my God. Why have you forsaken me? [50]

Then, we read that the curtain of the tabernacle in the Temple of God was suddenly torn in half, symbolizing that the separation between men and God had finally disappeared. Through the death of Jesus Christ, access to God was no longer limited to the high priests, but was available to all people.

Finally, at the very end, a Roman officer (of all people) recognized Jesus for what he was, saying:

Truly this man was the son of God. [162]

Then, Jesus’s body was taken from the cross and placed in a tomb, but three days later, it was found empty, for he had risen from the dead. In the other Gospels, the resurrection is followed by Jesus making appearances to his followers and his subsequent ascension to heaven.

Fig. 347 – Crucifixion by Rembrandt (17th century) (Boston Museum of Fine Art, Unites States)

The Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew contains many of the same stories as Mark, often in identical wording, but there are also some crucial differences. For instance, Matthew placed more emphasis on Jesus’s Jewish descent. He started his Gospel with a genealogy, linking Jesus all the way back to Abraham. The text states there were fourteen generations from Abraham to King David, fourteen from David to the destruction of Israel by the Babylonians, and fourteen further till the birth of Jesus. In this way, Matthew immediately placed Jesus at the end of a series of pivotal events in Jewish history.

In the other Gospels, Jesus was born in Nazareth, which was a small town of little significance. In fact, in John, when a disciple is told that the prophesied Messiah came from Nazareth, he responded, “Nazareth? Can anything good come from Nazareth?” Emphasizing Jesus’s Jewish descent, Matthew changed his birthplace to Bethlehem, the home town of King David, linking Jesus to a prophecy by Micah (8th century BC) which stated that the “savior would come from Bethlehem.”

We then read that Jesus’s mother, Mary, was impregnated by the Holy Spirit and was still a virgin when Jesus was born. Shortly after his birth, three wise men found Jesus while following a star, claiming they came to worship him:

Where is the one who has been born king of the Jews? We saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him. [50]

When the Roman King Herod (c. 74 BC–4 AD) learned about the “king of the Jews,” he felt threatened and wanted the child killed. But not knowing where to find Jesus, he ordered his soldiers to kill every child two years and under, an event known as the Massacre of the Innocents. When Jesus’s legal father, Joseph, learned about this in a dream, he fled with his family to Egypt. The story is clearly crafted to closely resemble the story of Moses, again linking Jesus to Jewish history.

Another clear connection with Moses occurs later in the text, when Jesus climbed a hill to deliver his Sermon on the Mount, which mirrored Moses’s climb of Mount Sinai. In this sermon, Jesus pushed Mosaic Law to the next level:

You have heard that it was said to those of ancient times, “You shall not murder;” and “whoever murders shall be liable to judgment.” But I say to you that if you are angry with a brother or sister, you will be liable to judgment; [...] You have heard that it was said, “You shall not commit adultery.” But I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her in his heart. If your right eye causes you to sin, tear it out and throw it away; it is better for you to lose one of your members than for your whole body to be thrown into hell. [163]

There were also moments when Jesus clearly departed from Mosaic Law. Generally, Jesus adhered to the spiritual and ethical commandments of Judaism but rejected its archaic rules and rituals. For instance, he was criticized by Jewish leaders for healing a blind man on the sabbath, which is prohibited by Mosaic Law. In the Gospel of John, he responded to their criticism as follows:

Sabbath was made for people, not people for the Sabbath. So the Son of Man is lord even of the Sabbath. [164]

Also in the Gospel of John (although not in the oldest version), we read that Jewish leaders brought a woman before him who had committed adultery. The leaders asked Jesus:

Now, in the law, Moses commanded us to stone such women to death. What do you say?

Jesus told them:

‘‘Let the person among you who is without sin cast the first stone.” When they heard this, they went away one by one, beginning with the oldest, and he was left alone with the woman standing there. Then Jesus stood up and asked her, “Dear lady, where are your accusers? Hasn’t anyone condemned you?” “No one, sir,” she replied. Then Jesus said, “I don’t condemn you, either. Go home, and from now on don’t sin anymore.”

In Matthew, Jesus is also asked about what he considers the “greatest commandment in the law.” He responded:

“You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.” [Deuteronomy 6:5] The second is this, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” [Leviticus 19:18] On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets. [162]

The Gospel of Luke

The Gospel of Luke also starts with a genealogy of Jesus, but Luke gave different names and started with Adam instead of Abraham. In this way, Luke emphasized that Jesus was not just here to fulfill the prophecies of the Jews, but instead to save humanity as a whole. In his version of the story, Jesus was rejected by the Jewish community and instead brought his message to the gentiles, becoming the savior of the entire world. Instead of hiding his identity as the Messiah, as he did in Mark, we now read he openly preached it in the synagogue, after which the crowd became outraged and attempted to kill him.

Luke also placed a stronger emphasis on helping the poor and the needy. Whereas in Matthew, we read, “blessed are the poor in spirit,” Luke simply wrote, “blessed are the poor.” Instead of “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness,” Luke states, “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst.” So, in Luke, being poor became a virtue in and of itself.

In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus also tells the famous Parable of the Good Samaritan. The Samaritans formed a separate branch of Judaism that was rejected by the mainstream due to doctrinal differences. A lawyer tested Jesus by asking him how to “inherit eternal life.” Jesus responded that the answer was to follow the Law, specifically to “love the Lord your God […] and your neighbor as yourself.” The lawyer then asked “Who is my neighbor?” Jesus replied with a story:

“A certain man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and he fell among robbers, who both stripped him and beat him, and departed, leaving him half dead. By chance, a certain priest was going down that way. When he saw him, he passed by on the other side. In the same way a Levite also, when he came to the place, and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a certain Samaritan, as he traveled, came where he was. When he saw him, he was moved with compassion, came to him, and bound up his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. He set him on his own animal, and brought him to an inn, and took care of him. On the next day, when he departed, he took out two denarii, and gave them to the host, and said to him, ‘Take care of him. Whatever you spend beyond that, I will repay you when I return.”

“Now which of these three do you think seemed to be a neighbor to him who fell among the robbers?” He said, “He who showed mercy on him.” Then Jesus said to him, “Go and do likewise.”

In Luke, Jesus also dealt differently with his fate. Whereas in Mark, we see a great emphasis on his suffering, in Luke, Jesus showed much less agony and was mostly calm and in control. For instance, in the Garden of Gethsemane, Jesus skips the line “My soul is troubled unto death.” He also does not fall on his face but only kneels down. Instead of saying, “Take away this cup from me,” he says, “If it be your will, take away this cup from me.” Also, in Mark, Jesus is mostly quiet near the end, while, in Luke, he speaks often and with confidence. When nailed to the cross, he famously says:

Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing. [50]

In Mark, both criminals who were crucified next to him mocked him, but in Luke, we read:

One of the criminals who hung there hurled insults at him: “Aren’t you the Messiah? Save yourself and us!” But the other criminal rebuked him. “Don’t you fear God,” he said, “since you are under the same sentence? We are punished justly, for we are getting what our deeds deserve. But this man has done nothing wrong.” Then he said, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” Jesus answered him, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise.’’

Remarkably, even Jesus’s final words are different in Luke:

Jesus called out with a loud voice, “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit.” [Psalm 31:5] When he had said this, he breathed his last.

The Gospel of John

The Gospel of John starts by mentioning the Greek concept “logos,” which originally meant “word” or “reason,” but which had gained an elevated meaning in Greek philosophy. Observing order and regularity in the cosmos, Pythagoras supposedly concluded that the world was governed by logos, or “divine reason.” Many other Greeks, including Plato and the Stoics, would also take up this idea. Here, at the start of this Christian text, we suddenly find the concept connected with Jesus himself:

In the beginning was the Word [“logos”], and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things were made. […] The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth.

John shows the least overlap with the other Gospels. We don’t read about Jesus’s baptism, nor his temptation in the wilderness, his famous parables, the casting out of demons, the Last Supper, the prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane, his trial before the Jewish authorities, and many other important scenes. John doesn’t even proclaim the coming kingdom of God. This omission has a simple explanation. The Gospel of Mark was written 20 years after Jesus’s death. At that time, Jesus’s prophecy that the world would end within a generation could still come true. Luke, another 15 years later, mentions the kingdom less often, and John, another 10 years later, doesn’t mention it at all. There are also a number of stories that appear only in John. We read, for instance, that Jesus turned water into wine and that he raised Lazarus from the dead.

In Mark, Jesus is secretive about being the Messiah and the Son of God, but in John, he openly tells it to the world. In Matthew, Jesus refused to perform miracles to prove he was the Messiah, but in John, he deemed it necessary to perform miracles for the people to believe him. In Matthew, Jesus raised Jairus’s daughter from the dead, with only the parents and three disciples present, and ordered them to keep what they saw a secret. In John, in contrast, Jesus intentionally waited for the sick Lazarus to die so he could raise him from his tomb as a public display of his powers. We read:

Then Jesus looked up and said, “Father, I thank you that you have heard me. I knew that you always hear me, but I said this for the benefit of the people standing here, that they may believe that you sent me.” When he had said this, Jesus called in a loud voice, “Lazarus, come out!” The dead man came out, his hands and feet wrapped with strips of linen, and a cloth around his face. Jesus said to them, “Take off the grave clothes and let him go.’’

In John, Jesus even called himself equal to God. In the other Gospels, Jesus was called the son of God, but this title had been used in the Old Testament for all sorts of people and did not indicate that he was anything other than a mortal man. In John, however, we read:

I and the Father are one.

Fig. 348 – Raising Lazarus from the dead, by Giotto (c. 1304) (Scrovegni Chapel, Italy)

His Jewish audience did not appreciate this blasphemy:

Again, his Jewish opponents picked up stones to stone him, but Jesus said to them, “I have shown you many good works from the Father. For which of these do you stone me?” “We are not stoning you for any good work,” they replied, “but for blasphemy, because you, a mere man, claim to be God.”

As we have read, at the start of John, Jesus is even described as pre-existing the universe as the “Word of God.”

John also tells us that God sacrificed his own son out of love for mankind. The word love (agape) often occurs in John and is famously equated with God himself:

Beloved, let us love one another, because love is from God; everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love. God’s love was revealed among us in this way: God sent his only Son into the world so that we might live through him. In this is love, not that we loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the atoning sacrifice for our sins. [162]

The Gospel of Thomas

There are also a number of gospels that didn’t make it into the New Testament. Many of these were only rediscovered in the last century. One of them is the Gospel of Thomas (1st or 2nd century), which is not a biography but a collection of sayings attributed to Jesus.

Thomas provided yet another interpretation of the Kingdom of Heaven. Instead of it being a physical installment of a kingdom on earth, he spoke of it as a spiritual awakening. We read:

His disciples said to him, “When will the kingdom come?” “It will not come by watching for it. It will not be said, ‘Look, here!’ or ‘Look, there!’ Rather, the Father’s kingdom is spread out upon the earth, and people don’t see it.”

Jesus said, “If your leaders say to you, ‘Look, the kingdom is in the sky,’ then the birds of the sky will precede you. If they say to you, ‘It is in the sea,’ then the fish will precede you. Rather, the kingdom is within you and it is outside you. If you will know yourselves, then you will be known and you will know that you are the sons of the Living Father. But if you do not know yourselves, then you are in poverty and you are poverty.” [165]

This idea might have already appeared in Luke in the following controversial verse:

Once Jesus was asked by the Pharisees when the kingdom of God was coming, and he answered, “The kingdom of God is not coming with things that can be observed; nor will they say, ‘Look, here it is!’ or ‘There it is!’ For, in fact, the kingdom of God is among [or within] you.” [164]

In some verses, the Gospel of Thomas gets close to the Buddhist idea that “all things are Buddha things.” We read:

Jesus said, “I am the light that is over all things. I am all: from me all came forth, and to me all attained. Split a piece of wood; I am there. Lift up the stone, and you will find me there.” [165]

Gnosticism

A loosely organized movement known as Gnosticism peaked between the 2nd and 4th century AD, until it was repressed as heresy. The Gnostics took a Platonic view of the world, contrasting the corrupt material world with an ideal spiritual world above. In their view, which they likely took from the Greek Hermetic philosophy, the material body was nothing more than a prison into which our souls were trapped. The goal became for this soul to escape the body and return to God.

Interestingly, the Gnostics turned the Biblical story on its head. In their view, the material world was created by an inferior and demonic god, who did not know the spiritual world. They identified this god with the “jealous” and “angry” God of the Old Testament. Yet in the spiritual world, they claimed, there exists a perfect God. It was this God who first created Adam “in his image,” as is described in Genesis I. The evil god of Genesis II thereafter created the lower material Adam. Wanting to keep Adam ignorant of his spiritual nature, the evil god tried to prevent him from eating an apple that would give him the knowledge (“gnosis”) to escape from the material world. The snake, who according to the Gnostics was good, convinced them to eat the apple, after which the jealous god threw them out of paradise, preventing them from also eating from the Tree of Life. In the Testimony of Truth (c. 300 AD), we read about this:

But what kind of God is this? First, he forbids Adam to eat from the Tree of Knowledge, and then he says, “Adam, where are you?” That god has no foreknowledge […]. And then he said, “Let us cast him out of this place, for otherwise he will forever eat from the Tree of Life.” Surely, he has revealed himself as treacherous and envious. [157]

Salvation finally came when Christ descended into an earthly man named Jesus in the form of a dove during his baptism. Christ helped the trapped souls to recognize their divine nature and escape from the material world towards the light of the spirit. According to Gnosticism, Christ departed the bodily Jesus just before his death on the cross, explaining the verse “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”