In its early stages, Christianity appealed especially to groups left voiceless in Roman culture, such as the poor, non-citizens, women, and slaves. What made Christianity appealing to these groups was its insistence on the equality of all people in the eyes of God, which was diametrically opposed to the hierarchical nature of Roman culture. From the start, Christianity also made great efforts to organize charities for the poor, feeding the hungry, and eventually providing free care to the sick. These innovations became so cherished that many Roman citizens lost interest in paganism.

The early Church Fathers did have to contend with the supremacy of Greek philosophy and worked hard to formulate a version of Christianity not in conflict with its great insights. Others turned away from science and civilization to live a life of prayer either as hermits or monks.

Until the fourth century, Christians remained a small minority in the Roman Empire, but this changed when Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity and made it the official state religion.

The Spread of Christianity

The early spread of Christianity, from 30 to 62 AD, is described in the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament. Since many of its details check out, this text has some historical credibility. In the Acts, we read that the main characters behind the early spread were Saint Paul and Saint Peter. The expansion was rapid, as within 25 years, Christian communities had been set up in Palestine, Syria, Asia Minor, Greece, and Rome. In this period, Christians generally came together in private houses, where they shared meals, performed baptisms, prayed, and listened to preachers. In order to coordinate the spread, Paul sent regular letters to various Christian communities, which are also included in the Bible. Peter is mentioned in the Bible as the leader of the church of Jerusalem, yet later Christian tradition tells he also founded a church in Rome and served there as bishop until he died as a martyr.

Fig. 349 – Wall painting from the house church in Dura-Europos depicting Christ and Peter walking on water (232 AD) (Yale University)

As Christianity continued to grow in the first centuries, it required a more sophisticated organization. The administration became more centralized and considerable effort was made to ensure homogeneity among the various communities. The leaders of the churches, called bishops and deacons, were described by Paul in the New Testament as secular leaders, who were responsible for instruction, settling disputes, and administering community welfare. No religious significance was attached to their roles at this stage, but this changed in the early 2nd century. For instance, it was decided that only bishops could perform the eucharist, which turned from an intimate meal into a sacrifice executed by a priestly class. In the same century, bishops were also granted the power to forgive sins after a person performed some kind of penance.

In the 3rd century, Christians began to meet in simple house churches rather than in private households. The earliest house church was excavated at Dura-Europos in Syria, which included a baptistery and various simple frescoes depicting scenes from the life of Jesus.

The martyrs

From early on, Christians were persecuted by the Roman authorities. To understand why this happened, we have to understand Roman religion. Like most cultures of the time, the Romans were a superstitious people. Even many educated Romans frequently consulted astrologers to inquire about their future and some even consulted sorcerers to place curses on enemies. On top of this, the Romans recognized a large pantheon of gods and half-gods. Even geological features, such as rivers and mountains, and abstract concepts, such as victory (Victoria) and luck (Fortuna), were associated with gods. Even some Roman emperors were deified, sometimes even during their lifetime.

The Romans were generally very tolerant of other religions. In fact, they often incorporated conquered peoples’ gods into their own religion—a process called syncretism. For instance, most of the Roman gods and heroes were Romanized versions from the Greek tradition. Zeus became Jupiter, Ares became Mars, Aphrodite became Venus, Poseidon became Neptune, Herakles became Hercules, Odysseus became Ulysses, and so on. Individuals were generally free to worship the gods they preferred, with one exception. All Romans were expected to worship the state gods, including Jupiter and Mars, since they were believed to control the stability and success of Rome. This practice brought the Romans into conflict with the Jewish and Christian communities, who were only willing to worship their one God. To the Romans, this was considered highly offensive—even treasonous—since they equated the rejection of their state gods with a rejection of Roman society itself. Many Romans also feared that disrespecting the state gods would cause them to show their wrath, for instance through horrible natural disasters and invasions. The early Christian theologian Tertullian (155–222), wrote about this:

When the Tiber overflows its banks, when the Nile floods, when the sky withholds rain, when there is an earthquake, famine, drought, or plague, then the people cry out to heaven: “The Christians to the lions.” [157]

Another conflict arose under Emperor Decius (c. 201–251), who issued a decree stating that every citizen of the empire had to make an offer to the emperor’s “genius” (his guiding spirit). Although it was just a minimal offer (a pouring of wine and a few incense grains), many Christians could not reconcile it with their faith. Christians were generally taught to obey the law, but honoring an emperor as a god just went too far.

Following Jesus as their example, a number of Christians willingly became martyrs, maintaining their religious beliefs in the face of the death penalty. Contrary to what the Romans intended, this caused them to be regarded as great heroes and exemplary disciples of Christ. The earliest martyr was Saint Stephen (c. 5–34), a deacon from Jerusalem who was stoned to death for his convictions by a Jewish court. Present at his stoning was a man named Saul, who at the time approved of the killing, but later converted to Christianity and became known as Saint Paul. Both Peter and Paul are said to have died as martyrs in 64 AD during the persecution of Nero.

At first, the persecution of Christians was sporadic, adding up to perhaps a few hundred victims in the first two centuries, but this started to change in the 3rd century. In 250 AD, Emperor Decius issued an edict that resulted in empire-wide persecutions. This resulted in the deaths of some notable Christians, including Pope Fabian. The persecutions were the worst under Emperor Diocletian (244–311 AD) and his successors, who attempted to unify the empire by making traditional Roman religion the standard.

Fig. 350 – Persecution of Pope Sixtus II under Emperor Valerian, from The Life of Saints (14th century) (Bibliotheque Nationale de France)

The Conversion of Constantine

Things eventually turned in Christianity’s favor. In 306, the popular general Constantine (c. 272–337) was acclaimed emperor by the British troops of the Roman Empire. In a series of civil wars, he finally defeated his co-emperor and rivals, becoming the sole ruler of Rome in 324 AD. The night before one of these conflicts, in 312, Constantine had a dream in which God appeared to him. God promised to aid him in battle if his men would put the chi-rho symbol on their shields (“chi” and “rho” are the first two letters of “Christ” in Greek). As a result of this vision, Constantine converted to Christianity, becoming the first Christian emperor. One year later, in 313, he managed to convince his co-emperor to sign the Edict of Milan, which ended the persecution of Christians by allowing all citizens to worship whichever god they chose.

Fig. 351 – Constantine (4th century) (Jean-Christophe Benoist, CC BY-SA 3.0; Capitoline Museum, Italy)

According to some, Constantine’s conversion was just a ploy to motivate his troops, especially since he earlier, in 310, had a vision of Apollo promising him victory in battle. He also associated with the sun god Sol Invictus, whom Emperor Aurelian (c. 214–275) had earlier elevated to an official state god. He continued to issue coins with this pagan god until AD 323, more than a decade after his conversion to Christianity.

Despite his fickleness, he did become a strong supporter of the Christian cause. He promoted Christians to high office, converted various pagan temples into Christian churches (including the Pantheon in Rome), and also built grand basilica churches, including the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, which was supposedly built on the site of Jesus’s burial. He also made Christian symbols appear on coins, military shields and banners, and paid for the copying of 50 Bibles. Constantine also actively set out to resolve various theological disputes. In 325 AD, he famously presided over the Council of Nicaea, where over 300 bishops determined that all three components of the Holy Trinity (God, Christ, and the Holy Spirit) had the same divine essence. A priest named Arius, who had maintained that Jesus was inferior to God, was subsequently excommunicated. In general, however, Constantine allowed for religious freedom. This changed when his son, Constantius II (317–361), came to power. He prohibited pagan sacrifices and closed various pagan temples.

In 361, paganism made one short comeback, when Julian the Apostate (c. 331–363) converted to paganism shortly before becoming emperor. Julian restored the pagan temples but did not actively persecute Christians. All his successors, with the exception of Eugenius (d. 394), would all be Christians.

In 380, Emperor Theodosius I (347–395) issued an edict, known as the Edict of Thessalonica, in which he imposed Christianity on all inhabitants of the empire, making it the exclusive state religion. The edict stated that only those who accepted the Trinity as was established at the Council of Nicaea were entitled to call themselves “Catholics,” while the rest were judged “demented lunatics.” He also closed pagan temples, including the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, forbade pagan worship, and made sacrifices to the pagan gods punishable by death.

More than a century later, in 529 AD, the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian (482–565), who built the famous Hagia Sophia (see Fig. 338), closed Plato’s Academy.

The appeal of Christianity

Constantine’s conversion was unexpected, considering Christians formed a minority of at most five to ten percent of the population. They were also just one of many religious sects. The religion did, however, have some unique selling points that made it appealing. For instance, while Roman religion was mostly collective in nature, with sacrifices and prayers often taking place during religious festivals and typically on behalf of groups rather than individuals, the focus of Christianity was much more personal. Christians were encouraged to pray indoors and alone, where they worked on a personal relationship with God. Christianity also promised an eternal afterlife for those who led a moral life. In contrast, most pagan religions did not have well-developed notions of an afterlife, nor were their gods overly concerned with morality. Morality, instead, was considered a topic for philosophers.

But Christianity did more. It threatened to overturn the entire Roman social hierarchy. According to Christianity, every human being is innately valuable and equal in the eyes of God. As a result, Christianity gave voice to groups generally excluded from the Roman system, including the poor, non-citizens, women, and slaves. Not surprisingly, therefore, many of the earliest converts to Christianity came from the lower end of the Roman social hierarchy. True to their principles, these neglected groups were also allowed to lead Christian congregations. Already in 112 AD, we read in a letter by Pliny the Younger (c. 61–113) to Emperor Trajan that a congregation was led by female slaves. Another influential female Christian was the Desert Mother Saint Melania the Younger (c. 383–439). She was born into a wealthy family but donated her wealth to the church and the poor and turned to a secluded life in the desert, spending her life fasting and helping the poor. She managed to collaborate with the great Church Fathers of the day, including Saint Augustine, and founded several monasteries in Africa and Palestine.

The acceptance of slaves, however, did not mean they were opposed to the institution of slavery itself (almost everyone in the ancient world accepted slavery as a given). An exception was Bishop Gregorius of Nyssa (c. 335–395) who called owning slaves a grave sin, as he believed all humans belong to God and therefore could not have a human master.

Charity in Greece and Rome

One other distinguishing feature of Christianity and Judaism, as opposed to Greek and Roman culture, is its emphasis on charity for the poor. Although hard for modern readers to understand, the Greeks and Romans had relatively little interest in helping the poor—not even in theory. This is ironic, since the Greeks developed the branch of philosophy known as ethics—the study of morality. They went to great lengths to describe virtuous behavior. They wrote about justice, hospitality, generosity, benevolence, and so on. Yet these words were only occasionally applied to the poor in particular. [166] Instead, it was common in Greece to believe people were only deserving of generosity if they were at least able to return the favor at a later time. The poet Hesiod, for example, wrote:

Give to him who gives, but not to him who does not give. [166]

Only occasionally do Greek and Roman writers praise selfless giving. And even then, it was believed that one should only give to the deserving poor.

Plato, for instance, wrote about this:

The true object of pity is not the man who is hungry or in some similar needy case, but the man who has sobriety of soul or some other virtue, or share in such virtue, and also experiences misfortune.

Aristotle wrote that virtuous men should only give to the “right people”—to those who are worthy of the gift. In his Politics, he claimed money should not be spent on free hand outs, “because this way of helping the poor is the legendary jar with a hole in it” (although he did believe that it was important to combat extreme poverty to keep democracy stable).

The poor were also often described as unvirtuous and immoral. It was commonly believed that poverty forced people to do bad things. And we also read the poor can’t be trusted as they might deceive people for money.

There was also little incentive to support the poor within the religious framework of the Greeks and the Romans. Jewish and Christian sentiments such as “God loves the poor” sounded nonsensical in the Greek and Roman tradition, as the gods were believed to reward good subjects with wealth. Instead, it was commonly believed that the poor had only themselves to blame. If a person was poor, this was a sign that the gods did not favor them, so they best be avoided.

There are—as always—some counterexamples, but even these often prove the rule. For instance, there was a strong tradition among Greek and Roman aristocrats to distribute wealth to the community. Yet their gifts were often aimed not at the poor specifically, but at society at large, for instance by paying for a public feast, a public building, an aqueduct, a school, or a library. Some of these men likely genuinely did this to help, yet it was mostly done to gain fame and honor. In fact, the Greek word for generosity, philotimia (related to “philanthropy”), actually meant “the love of honor.” For instance, Cicero remarked:

Most people are generous in their gifts not so much by natural inclination as by the lure of honor. [166]

There was also the patronage system, which allowed the poor with potential, for instance promising thinkers or artists, to get the financial means to express their talents. But this also wasn’t for the truly destitute, and it was often reciprocal, for the patron valued the produce or prestige of their clients.

Both the Greeks and the Romans did have a rudimentary welfare system. In Greece, this was reserved only for the roughest cases, as demanded by the Athenian democracy. In the text The Athenian Constitution, possibly written by Aristotle, we read:

The Council also inspects the Incapables; for there is a law enacting that persons possessing less than three minae and incapacitated by bodily infirmity from doing any work are to be inspected by the Council, which is to give them a grant for food at the public expense […]. And there is a Treasurer for these persons, elected by lot.

Starting with Gaius Gracchus (c. 154–121 BC) the Romans regularly passed laws to subsidize grain. But these laws were aimed at all non-elites and not the poor in particular. In principle, even aristocrats could apply. In fact, there is an account of Gracchus confronting an aristocrat waiting in the grain line. Most aristocrats, however, believed that the supply of “bread and circuses” to the poor was just a way to keep them in check. It was done mostly to resolve tensions between the elite and the commoners to avoid rebellion, instead of genuine altruism. [166]

We do have to make sure not to overstate the case, as some authors do. Of course there were Greeks and Romans who pitied the poor and the unfortunate, as empathy is a human universal. From Rome, for instance, we have inscriptions which directly speak of care for the poor. In one instance, we read of a man who came to the assistance of the poor in hard times and another one who sold grain at a very low price at times of scarcity. And on one tombstone, a man is described as “the Father of Orphans, the Refuge of the Needy, and the Protector of Strangers.” [167]

In speeches from Greece, we find some wealthy individuals boast about their own private charity. Demosthenes, for instance, boasts of helping “those in need” including providing dowries and ransoming prisoners of war who were too poor to buy their own freedom. Although Demosthenes does add that the recipients should remember it “for all time.” [168]

Various emperors were also known to help the poor. For instance, Emperor Trajan invested in an institution for the care of destitute children.

The Stoics, as usual, were also an exception to the rule. They believed all people, man or woman, poor or rich, slave or freeman, formed a brotherhood and therefore were deserving of compassion.

The Stoic Musonius Rufus (1st century AD) was known to give alms without expecting anything in return, believing he imitated God’s generosity in this way. The 3rd century AD biographer writes of him that he gave money to a beggar, after which a crowd objected that the beggar was “a bad and vicious fellow, deserving of nothing good.” Rufus then replied with a joke: “Well, then, he deserves money.” But do notice, here too, the crowd disapproves of the almsgiving. [169]

Finally, I have to mention the Greek concept of xenia, meaning hospitality to strangers. This habit can be traced back to the proto-Greeks and even further back to the Proto-Indo-Europeans, who were nomads. Nomadic tribes often find themselves in each other’s territory and in need of help, making hospitality mutually beneficial.

To encourage this behavior, Greek myths spoke of the god Zeus Xenios (Zeus of Strangers), who disguised himself as a stranger (xenos) to test the hospitality of human beings. Already in the Odyssey, we read:

It's wrong, my friend, to send any stranger away, even one who arrives in worse shape than you. All strangers and beggars come from Zeus. [166]

Although beggars are mentioned here, the focus was more often on strangers. As the Dutch scholar Van der Horst remarked, it is telling there was a Zeus Xenios (the protector of strangers) and a Zeus Hiketesios (the protector of refugees), but no Zeus Ptochos, no Zeus of the poor.

And it also is the question to what extent the principle was put to practice after the Greeks had settled down. The social critic Theognis (6th century BC), for example, wrote that to be a stranger was among the worst fates imaginable.

Blessed are the poor

The situation was very different in Judaism, where charity was seen as one of the best ways to honor God. And Yahweh is regularly described as the God of the poor and the unfortunate. In the Old Testament we read:

Whoever oppresses the poor shows contempt for their Maker, but whoever is kind to the needy honors God. [50]

This made the care for the poor a divine commandment.

Mosaic Law also requires that one tenth of produce grown in the third and sixth year of the seven-year sabbatical cycle be given to the poor. This became known as the poor tithe.

In the 3rd century BC, charity even became a means to forgive sins. This idea evolved slowly over centuries. At first, the main path to redeem sins was to participate in the sacrifices at the Jewish Temple. This changed somewhere during the 8th century BC, when prophets such as Hosea proclaimed that sacrifices were secondary, or even unnecessary, compared to helping the needy. In Hosea, for instance, God says:

I desire mercy, not sacrifice. [157]

When the Old Testament was translated into Greek in the 3rd century BC, the Greeks still didn’t have a word for almsgiving. The Jewish translators decided to use ele(-)emosyne, originally meaning “compassion” or “mercy.” This concept was then related to the forgiveness of sins through a translation error [169]. A verse in Daniel (“Redeem your sins by practicing righteousness”) was now translated as:

Redeem your sins by almsgiving.

At this point, however, collection of the poor tithe was not yet centralized but was instead left to the individual. This began to change in the second century, when rabbis in synagogues appointed officers to collect money and distribute food to the poor. In the Tosefta (3rd century AD), we read that their hospitality even extended to pagans:

The collector of funds for supporting the poor [...] supports both the poor of the pagans and the poor of Israel, for the sake of peace. [157]

Now the Christian case. Following the teachings of the Old Testament, Jesus taught that God loves the poor. Famously, we read in Matthew:

Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. […] Blessed are those who hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled. [50]

In The Gospel of Luke, these lines were amended to make poverty itself a virtue:

Blessed are you poor, for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessed are you who hunger now, for you shall be filled. [50]

For the word “poor,” the New Testament uses the Greek word “ptochos.” The Greeks since the days of Homer recognized two types of poverty. The penes had work but barely got by, while the ptochos experienced absolute and abject poverty. This was the group that Jesus addressed.

Early Christian communities created organized charities right from the start. Already in the early thirties of the first century, the Christians in Jerusalem appointed men to oversee the distribution of food to the widows in their communities. About fifteen years later, Paul organized a large-scale collection of money for the poor Christians in Jerusalem, ensuring “there was not a needy person among them.” Both Jews and Christians also emphasized that it was best to give alms when nobody was looking, to distinguish true altruism from the self-aggrandizement of the Romans.

The success of Jewish and Christian charity becomes evident in a letter from Julian the Apostate (c. 331–363) to a pagan high priest, in which he admitted that the charity of Jews and Christians made it difficult to persuade the public to return to paganism. We read:

[It] is disgraceful that, when no Jew ever has to beg, and the impious Galileans [Christians] support not only their own poor but ours as well, all men see that our people lack aid from us. [166]

He, therefore, ordered his priests to distribute food at public expense, not only to the “poor who serve the priests,” but also to “strangers and beggars.”

The first hospitals for the poor

Not long after, Christians also began to help the sick. Again, let’s first discuss the Greek and Roman case. First of all, the Greeks and the Romans had private physicians, who used secular medicine as developed by Hippocrates (c. 460–370) and Galen (c. 129–210). These doctors explicitly distanced themselves from magic and faith healers. But these doctors were generally only available to the rich. We only know of a couple of doctors who helped the poor free of charge.

The Greeks also had medical facilities known as Asclepieions which were (at least in theory) accessible to the poor. Yet these facilities were more like healing temples than hospitals. Patients slept in these temples, hoping the god Asclepius would visit them in their dreams and provide a cure. The doctors in the Asclepieions did also recommend dietary changes and even performed some types of surgery. Therefore, a case can be made to see them as proto-hospitals, yet most treatments had more in common with faith healing.

The Romans had hospitals for specific groups, such as wounded gladiators or soldiers. These hospitals often had professional doctors and even specialists, but they were not accessible to the general public (let alone the poor).

The Christians greatly expanded the care for the sick. According to Bishop Dionysius of Alexandria (3rd century), Christians were even willing to care for contagious victims of the plague. He wrote:

[They] visited the sick without a thought as to the danger, […] and so most gladly departed this life along with them. [170]

The first Christian proto-hospitals started in monasteries. The earliest known reference comes from Saint Pachomius in 324 AD who “appointed [a] house of stewards to give comfort to all the sick brothers with attentive care according to their rules.” Yet this was only accessible for monks and the treatment was mostly nonmedical. These monasteries often recognized various types of demonic afflictions and in some cases, they claimed illness was a test from God, which therefor did not require medical treatment, but only prayer and faith in God. Yet various monasteries did offer diets, pharmaceuticals, and sometimes even surgery. So, in that sense, they also count as proto-hospitals, just like the Asclepieions.

This changed with Saint Basil (330–378), who studied and taught Greek secular medicine and also defended its use. He wrote:

Just as each of the arts has been given us by God as a help to supplement the deficiencies of nature—for instance, agriculture, because what grows out of the earth of itself is not sufficient to relieve our necessities; weaving, because the need of coverings is paramount in view both of decency and the damage inflicted by the weather, […]—so it is with the medical art. Since our body, so subject to disease, is liable to various kinds of harm […] the medical art […] has been given us by God. [170]

Saint Basil also built the first proper hospital for the general public, which came to be known as the Basileias. It was located in central Turkey, although the precise location is not known. And, of course, doctors at his hospital were trained in secular Greek medicine. Basil’s friend Gregory wrote about this:

Go forth a little way from the city, and behold the new storehouse of piety […] where disease is regarded philosophically, and disaster is put to the test. [170]

The Basileias was a vast complex that included (besides a hospital) an orphanage, a leprosarium, a house for the poor, a hostel for travelers and the homeless, storehouses, a kitchen, stables, workshops, housing for staff, a monastery, a church, and more. Understandably, the complex was called “a new city”. Basil also called his hospital a “place for the care of the poor” (ptochotropheion) and also a place for the care of orphans (orphanotropheion) and even a place for the care of lepers (keluphokomeion). The leprosarium deserves some extra attention. Lepers were often considered to be the most wretched of the Earth. As lepers were an economic burden and had a risk of contagion, they were often shunned by society and displaced to the outskirts of cities, where they often lived not unlike animals. But under Basil, they were “no longer the objects of hatred, but instead of pity on account of their disease.” Basil himself worked in the leprosarium as an example to others.

Basil also cared for the orphans. He wrote:

We are of the opinion that every age, even the very earliest, is suitable for their admission. And thus such children as have lost their parents we adopt of our own free will, being desirous, after the example of Job, to become fathers to the orphans.

This too was very different from the treatment of orphans by the pagan Greeks and Romans. In Rome, it was relatively common to find abandoned unwanted babies. Some were left on the side of the road, some in garbage dumps, in drainage ditches, or in front of temples. Sometimes slave traders would take these children away. Also, a child was only recognized as a member of the family after the father had lifted the baby up. Before that time, infanticide was not considered a crime. [157]

In his funeral oration, his friend Gregory wrote that Basil’s hospital easily surpassed the “wonders of the world”:

Go forth a little way from the city [of Caesarea], and behold the new city [the Basileias]. […] Why should I compare with this work Thebes of the seven portals, […] and the walls of Babylon, […] and the Pyramids, and the bronze […] of the Colossus, […] from which their founders gained no advantage, except a slight meed of fame. My subject is the most wonderful of all, the short road to salvation, the easiest ascent to heaven. [170]

Within a few decades, hospitals became commonplace in the Eastern Empire. Some of these hospitals even treated non-Christians.

Although less well-documented, India also saw the development of hospitals for the general public. The first concrete evidence comes from Fa Xian, a Chinese Buddhist monk who travelled across India around 400 AD and documented his observations in his Records of Buddhist Kingdoms. He wrote:

The heads of the Vaisya families establish in the cities houses for dispensing charity and medicines. All the poor and destitute in the country, orphans, widowers, and childless men, maimed people and cripples, and all who are diseased, go to those houses, and are provided with every kind of help, and doctors examine their diseases. They get the food and medicines which their cases require, and are made to feel at ease; and when they are better, they go away of themselves. [171]

It is conceivable that these hospitals even preceded their Christian counterparts.

The Age of Monks

The third century also saw the beginning of the monastic movement, which started in Egypt and Syria. The first Christian monks were ascetic hermits (the word “monk” is derived from “monochus,” meaning “one who lives alone”). To bring themselves closer to God, they purposefully rejected the imperfect material world, including society and even their physical bodies. In the words of John Climacus (6th-7th century AD):

Withdrawal from the world is a willing hatred of all that is materially prized, a denial of nature for the sake of what is above nature. [51]

These early hermits, known as the Desert Fathers, left their families, renounced their property, reduced food intake and sleep, abstained from sex, and spent long hours praying under tough circumstances. Their bodies were often underfed and scarred by their lifestyle, yet it was believed that their minds were purified through the ordeal. Some spectators claimed that despite their battered bodies, they gave off an almost angelic glow, as though they had returned to the state of Adam in paradise. We read, for instance, that Father Or’s (4th century) “face was so radiant that the sight of him alone filled one with awe.” A monk looking into Father Arsenius’s cell saw the old man as a “flame.” [51]

The most important early hermit was Saint Anthony (251–356). His biography was written down within a year of his death by Bishop Saint Athanasius (c. 296–373), who knew him well. Here, we read that Anthony was born into a wealthy family and had little formal education. He never learned to read, giving him access to Bible passages by memory alone. At eighteen, he became an orphan. A few months later, he entered a church, where he heard a gospel passage in which Jesus tells a rich young man: “If you wish to be perfect, go, sell your possessions, and give it to the poor; and come, follow me and you will have treasure in heaven.” Taking these words as a direct command to himself, he gave away his possessions to the poor. He then became the disciple of a local old hermit, where he spent his days combining prayer, fasting, and manual labor. He ate only bread and salt, wore a hair shirt (which purposefully irritates the skin), and slept on the bare ground in line with the gospel verse: “when I am weak, then am I powerful.” He interpreted the temptations he felt for food, lust, fame, and money as a direct attempt by the devil to take him down. He claimed the devil chased him day and night, targeting him specifically because of his strong resolve. Bystanders “could perceive the struggle going on between the two,” but he remained steadfast in his belief in Christ, which made the devil powerless against him. [172]

After a few years, Anthony moved into a deserted tomb near his village. He asked a friend to lock the door behind him and bring him bread at every few months. It was here that he had his most memorable encounter with the devil:

He [the devil] came one night with a great number of demons and lashed him so unmercifully that he lay on the ground speechless from the pain. [172]

The tomb began to shake and demons broke through the walls “in the forms of beasts and reptiles. […] The place was filled with the phantoms of lions, bears, leopards, bulls, and of serpents, […] scorpions, and of wolves.” As the animals attacked him, he felt severe pain in his body, but his mind remained in control. Then the Lord came to help him, opening the roof of the tomb and sending in a beam of light, which chased away the demons and restored the building to its former condition.

At the age of 35, he moved from his tomb to a deserted Roman fort, where he stayed for 20 years in solitude, while his friends would throw bread over the walls every six months. After twenty years, his friends forced open the door, and while expecting to find him in bad shape, he had kept his former appearance and was “filled with the spirit of God.” Once out of the fort, he moved to the Egyptian desert, where he preached, performed miracle cures, and became the leader of a group of monks. The number of monks quickly grew to the point where “the desert was made a city by monks who left their own people and enrolled for citizenship in heaven.” The monks sometimes joined Anthony, but usually lived alone. “Their solitary cells in the hills were like tents filled with divine choirs singing Psalms, studying, fasting, praying, rejoicing in the hope of the life to come, and laboring in order to give alms and preserving love and harmony among themselves.” [172]

After a few years, Anthony heard Christians were persecuted in Alexandria. He then travelled to the city hoping to be martyred. Once there, he attended to the needs of Christian prisoners, whom he supported in court and all the way to their death on the scaffold. Against his own wishes, Anthony’s own life was spared when the persecution ended with the Edict of Milan in 313 AD.

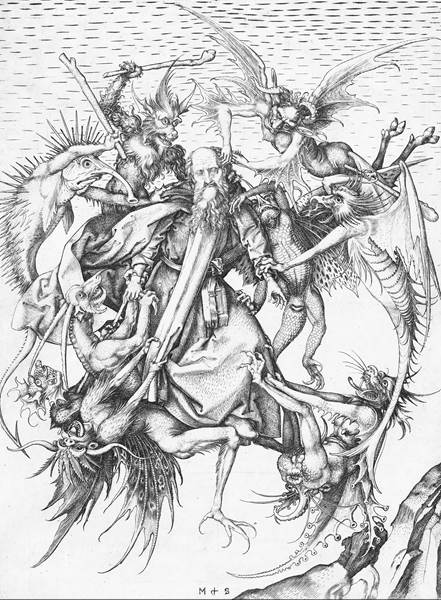

Fig. 352 – The Temptation of Saint Anthony, by Martin Schongauer (c. 1470) (MET, United States)

As his place in the desert had become overcrowded, he found himself another spot, where he spent the last 45 years of his life. It was in this location that he finally passed away with a cheerful look on his face. His biographer tells us he had “gained renown not for his writings, nor for worldly wisdom, nor for any art, but solely for his service to God.”

The most eccentric ascetics were the pillar-saints. The first of these was Saint Simeon Stylites (c. 390–459), who climbed a pillar in Syria in 423 AD and remained there until his death 37 years later. He used the suffering caused by the lack of movement and the intense heat of the sun to purify his soul. For sustenance, boys from a nearby village would climb the pillar to bring him food and drinks. His dedication attracted many visitors to his pillar to listen to his sermons. His fame even prompted men of great importance, such as Emperor Theodosius, to correspond with him, asking for his advice.

A collective form of monasticism came into existence in the fourth century and was formally institutionalized by Saint Benedict (c. 480–547), the son of a senator, who sold his possessions and founded various monasteries in Sicily and also one in Rome. His Rule of Benedict became the most influential guide for monastic life. Instead of the extreme suffering of the hermits, his rule was realistically achievable for the average practitioner. Benedictine monks should “call nothing their own,” yet they were allowed to have shared possessions. Their daily activities could be summed up by the motto “ora et labora” (“pray and work”). The work referred to manual labor, such as cooking, washing, tailoring, farming, herding, and later also the brewing of beer. Over the centuries, when monasteries became more prosperous, the manual labor dimension was often dropped in favor of intellectual work, including teaching and the copying of manuscripts. Ironically, monks were generally viewed as privileged in the Middle Ages. They lived in the most beautiful buildings, surrounded by expensive art, had a better diet than the average farmer, and some monastic groups held significant political power. Yet, in their defense, their commitment to education, art, and music, did make monasteries a rare bastion of literacy and philosophy in Europe during the Dark Ages.

In 1098, the Cistercians (named after the city Citeaux) branched off from the Benedictines in an attempt to return to a more rigorous observance of the Rule of Benedict. For this purpose, their monasteries were often located in isolated places, where they had to rely on agricultural labor to sustain themselves.

The 13th century saw the introduction of various mendicant (“begging”) orders, who rejected the communal monastic model. They owned no property at all and depended on the goodwill of the population for their survival. They often traveled from place to place, preaching in urban areas, especially to the poor. One of these orders was founded by Saint Francis of Assisi (c. 1181–1226), who gave away his father’s money without his permission to rebuild several churches. Enraged by this, his father disinherited him. In response, Francis stripped himself naked before the bishop in the town square of Assisi, gave his clothes back to his father, and declared he acknowledged no father but the one in heaven. With unparalleled joy and courage, Francis then set out to live in poverty in service to the poor. At some point, he even chose to live among lepers. “He washed their feet, bound up their wounds, pressing out the corrupt matter, and then washing and cleansing them. And having done this he kissed their wounds with great marvelous devotion.” [173] No matter how horrendous this sounds, he later claimed this was the most joyful period of his life.

Instead of joining an existing monastic movement, Francis set out to create an order of his own. Using his incredible charisma, he managed to arrange a meeting with the pope, who approved his order. His followers were expected to live in poverty, were not allowed to handle money, and should live in service to the poor. He expected his followers to suffer alongside the most unfortunate people of society. He even required them to live according to some of the most challenging (and profound) lines from the gospel, such as: “Foxes have dens and birds have nests, but the Son of Man [Jesus] has no place to lay his head” and “I am sending you out like sheep among wolves.”

Famously, Francis also delivered a sermon to the birds, following the commandment in the gospel to “go into all the world and preach the gospel to all creatures.” He “called them all his brothers and sisters, because they had all one origin with himself.” [173]

Near the end of his life, Francis is said to have witnessed an angel, who gave him the stigmata, the wounds Christ endured during his crucifixion, making his imitation of Christ complete. Suffering from these wounds, he died shortly thereafter.

Fig. 353 – Sermon to the birds, by Giotto (c. 1300) (Basilica of Francis of Assisi, Italy)

The Church Fathers

Late Antiquity was also the era of the Church Fathers, most notably Saint Augustine (354–430) and Saint Jerome (c. 347–420), who helped turn Christianity into an intellectual tradition that could compete with pagan philosophy. During their lifetime, Rome was sacked, and both theologians spent time making sense of what had happened. Jerome wrote:

The brightest light of the whole world is extinguished; indeed, the head has been cut from the Roman Empire. To put it more truthfully, the whole world has died with one City. Who would have believed that Rome, which was built up from victories over the whole world, would fall; so that it would be both the mother and the tomb of all people? [174]

Saint Augustine responded to the fall of Rome with a work called The City of God, in which he opposed the accusation by pagans that the sack of Rome had been caused by Christianity and their abandonment of the Roman state gods. Augustine pointed out that Rome had suffered catastrophes well before the emergence of Christianity. He also pointed to contradictions in paganism. The Romans had worshipped the gods of peoples whom they had conquered and then entrusted their defense to those gods, who had been unable to defend their original believers. He also attacked paganism for offering no moral guidelines and no heaven and hell as an incentive for good behavior. In dealing with the sack of Rome, he concluded that the city was not significant in the grand perspective of eternity. A true Christian, he claimed, recognized the city of God over the city of men.

The Church Fathers generally recognized the intellectual superiority of Greek philosophy, and spent time trying to work out its tensions with Christianity. Justin Martyr (100–165), who was martyred under Emperor Marcus Aurelius, attempted to show that Christianity could be brought in accord with reason. He added that some “just pagans” who had followed the “logos” (including, for instance, Socrates) also counted as Christians. Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–215), who became head of a Bible school in Alexandria, claimed that God had revealed himself to the Jews through Moses but also to the Greeks through philosophy. Clement was succeeded by Origen (c. 185–253), who, supposedly, castrated himself following a biblical verse. He was a Platonic thinker, who would first be martyred for his Christian faith, but would in the 6th century also be condemned by the Church for his overreliance on Greek thought. Origen famously interpreted the Bible allegorically, which helped him explain contradictions in the Bible. He also was the first to attempt to systematically define the axioms of Christianity in his On the First Principles. Saint Augustine was also deeply impressed with Greek thought. He concluded that reason was a gift from God, and, therefore, that all things discovered through reason should be accepted as truth, even when it came from a pagan source. Whenever scripture conflicted with reason, Augustine concluded it must be read metaphorically instead of literally. Otherwise, Christians would only embarrass themselves, making it more difficult to spread their faith:

If they find a Christian mistaken in a field which they themselves know well and hear him maintaining his foolish opinions about our books, how are they going to believe those books in matters concerning the resurrection of the dead, the hope of eternal life, and the kingdom of heaven, when they think their pages are full of falsehoods on facts which they themselves have learned from experience and the light of reason? Reckless and incompetent expounders of Holy Scripture bring untold trouble and sorrow on their wiser brethren when they are caught in one of their mischievous false opinions and are taken to task by those who are not bound by the authority of our sacred books. For then, to defend their utterly foolish and obviously untrue statements, they will try to call upon Holy Scripture for proof and even recite from memory many passages which they think support their position, although they understand neither what they say nor the things about which they make assertion. [175]

This enlightened opinion would influence thinkers for centuries to come, although not everyone agreed. Tertullian (155–222), who also formulated the doctrine of the Trinity, argued that Christian and pagan ideas should be kept far apart, stating:

What has Athens to do with Jerusalem? […] Away with all attempts to cobble together a mixed Christianity with Stoic, Platonic, and dialectical elements. We do not desire speculative debates now that we possess Christ Jesus, nor do we desire the search for Truth now that we have received the Gospel. [157]

Rejecting the supremacy of reason over faith, he proclaimed:

The Son of God was

crucified; I am not ashamed—because one ought to be ashamed of it. And the Son

of God died; it is credible, because it is absurd. And having

been buried he

rose again; it is certain, because it is impossible. [176]

Even Saint Jerome, who was classically educated, came to feel guilty for reading Cicero. He gave up reading pagan literature for a while, but then returned to it because he could not bring himself to neglect his library, which he had collected with “great care and labor.” He then felt extra shame when the language of scripture sounded “harsh and barbarous” in comparison. But at some point, he had a terrifying dream in which he believed he had died and was dragged before a tribunal of the Lord. When asked to “state his condition,” he replied “I am a Christian,” but the Lord responded: “You lie. You are a Ciceronian, not a Christian,” [122] after which he was severely lashed. He then vowed never again to read pagan literature. Later in his life, he diminished the importance of the dream and again picked up his beloved pagan literature. This tension between acceptance and rejection of pagan knowledge would continue to play an important role throughout Christian history.

The Vulgate

Saint Jerome was born in a Christian family, studied classical Latin under the great pagan grammarian Aelius Donatus (4th century), and also learned Greek and Hebrew. He was also well traveled, spending time in Jerusalem, Constantinople, Trier, Alexandria, and Antioch. Jerome lived for years as a hermit in the Syrian desert and later in Bethlehem. At the age of 35, he became a secretary to the pope, who assigned him the task of creating a new translation of the Bible in Latin, called The Vulgate, which would become the standard translation for over a thousand years. The pope asked for a new translation because he was concerned about the inconsistencies among the many Latin versions of the Bible. These translations were often written and rewritten by many different anonymous translators, often in poor provincial Latin. The pope wanted a responsible but also accessible translation by a single author. In the preface to his translation, addressed to the pope, Jerome explained his task:

You urge that I create a new work out of the old, to sit in judgment on copies of the scriptures, dispersed as these are all over the world, and, given that they vary among themselves, to decide which of them agree with the Greek truth. […] There are almost as many versions as there are codices. But if the truth cannot be found out from many exemplars, why not then go back to the original Greek and correct those things that were either poorly published by erroneous translators, or wrongly emended by presumptuous ignoramuses, or added or changed by sleepy scribes? [177]

Jerome discussed the difficulties he faced during his translation in a number of letters. He admitted it was likely he had made some mistakes in the process, as any human would:

Let them therefore take it from me that the stability of the churches is not endangered if I have omitted a few words in quick dictation. [178]

But in the Middle Ages, The Vulgate often came to be seen as the infallible truth, to such an extent that the church felt no need to ever turn back to the original Greek. As the text was written by a saint and commissioned by a pope, they saw no reason to doubt its accuracy.

The Confessions of Augustine

Augustine’s most influential book is called The Confessions, which describes his development from his “sinful” youth to his conversion to Christianity. Not insignificantly, it is the closest thing we have to an introspective autobiography in the ancient world. In this work, Augustine not only lists events from his life but also reveals much of his private thoughts and feelings, even when they were embarrassing. He did this to come clean about his past:

I am determined to bring back in memory the revolting things I did, and the way my soul was contaminated by my flesh—doing this not out of love for those deeds but as a step towards loving you [referring to God]. [179]

The Confessions is written directly to God. Cleverly, he wrote as though only God could hear his words, making the readers feel they are listening in on a very private conversation. He even claimed he was too embarrassed to reveal his thoughts to anyone but God:

I enter my plea before your mercy, not before a fellow man, who might well mock me. Or do you, in fact, mock me? But even if you do, you will change your mood and pity me. [179]

This (imaginary) sense of privacy allowed Augustine to speak freely. In an unprecedented way, it allowed him to “travel down into himself,” which he managed to do with remarkable clarity and humility. Augustine got this idea from the Neo-Platonists, the most famous being Plotinus (204-270). Plotinus believed all of reality had emanated in stages from “the One,” finally ending up in material reality. This divine origin, he believed, could be found by looking inward. Following Neo-Platonic thought, Augustine believed that God was to be sought within ourselves. His inner journey allowed him to better understand himself, which would in turn strengthen his relationship with God. This is why he claimed of his sinful past: “I was outside myself, while you were inside me,” and “[you were] deeper in me than I am in me.”

Yet despite this revolutionary approach, the work is not an autobiography in the full modern sense. Augustine wrote down the story of his life not for its own sake, but for its theological worth to the reader. He generally only mentioned life events that are somehow relevant to his eventual conversion. This might be why he leaves out some facts that would seem essential in a modern autobiography, such as the name of a dear friend who died at a young age.

Let’s now dive into the story of his life. We read that Augustine regretted his “sinful” past, which included his lustful feelings for women and the childish theft of a pear from his neighbor’s orchard, which he stole without being hungry. He also recounts a relationship with an unnamed woman he was not married to, with whom he had a son. They stayed together for many years, and he claimed to have been “faithful to her bed.”

The first step toward his awakening occurred when he read the now lost text called Hortensius by Cicero, which he initially wanted to read just to polish his rhetorical language skills. While reading, however, he was caught by the actual message of the text. It convinced him of the importance of seeking eternal truths. We read:

I reached a book by a man known as Cicero […] and it changed my life. [I came to pine] for deathless wisdom. […] I no longer read this book to acquire a speaker’s polish. […] I did not value it for its effect on style, since I was moved by what it said, not how it said it. […] Philosophy means the love of wisdom, which that book instilled in me.

Around this time, Augustine also took a look at the Bible, but he was not at all convinced:

I undertook then a close scrutiny of the Holy Scripture, to ascertain its worth. […] It seemed trivial next to Cicero’s majesty. My own loftiness was unfitted for its humility. [179]

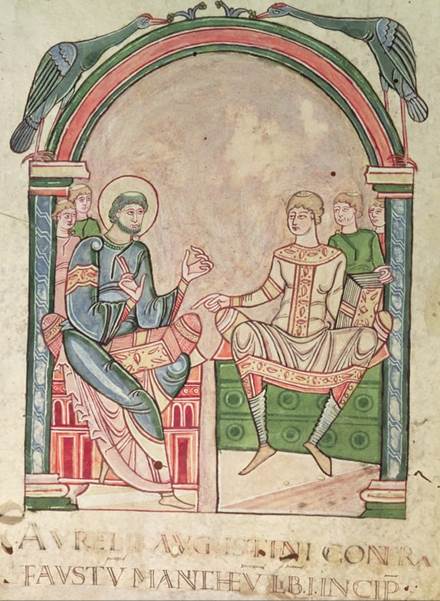

Fig. 354 – Augustine debating with Faustus in the presence of their pupils, from Saint Augustin Contre Faustus (12th century)

He then sought answers among the Manichaeans, a sect originated by the Persian prophet Mani (3rd century AD). Mani’s teachings included elements of Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Buddhism and spread all the way from Rome to China. Augustine remained affiliated with them for over ten years. He later recognized that the Manichaean conception of God had kept him from his spiritual development. The Manichaeans saw God as a “physical being of great size and splendor” and also believed the existence of evil proved that God was not omniscient but in constant conflict with the forces of evil. When a dear friend died at an early age, Augustine realized these concepts were of no help to him whatsoever:

If I tried to put weight on [it], [it] crumbled.

Meanwhile, Augustine took a great interest in the sciences, which he mastered with exceptional ease:

I mastered rhetoric and logic, geometry, music, and mathematics, easily and without the need for an instructor. […] I found that the quickest students were simply the least slow in trying to follow me.

His study of astronomy would eventually make his belief in Manicheism untenable. Mani had included a lot of specific astronomical claims in his teachings, but they proved inferior to the claims of natural philosophy:

I had been reading widely in the philosophers and turning over in my head what they said. When I matched them against the large imagined claims of the Manichaeans, I found them more successful in explaining the universe. […] They predicted, years ahead, eclipses of the sun and moon, partial or total, down to the day and the hour, and their calculations turned out right. […] Whatever truth they had uncovered about your universe I accepted, since I found method in their calculations. […] I contrasted it with what Mani had so extensively written. […] Belief was demanded in Mani’s sayings, whereas rational method was used in the secular calculations, and evidence capable of visible proof. The contrast was glaring. […] Mani, who did not know astronomy, had the sheer gall to teach it. […] How, after he was refuted by those with a sound understanding of astronomy, could he be trusted in matters more difficult to understand? [179]

When he discussed these concerns with the Manicheans, they time and again assured him that the Manichean bishop Faustus (see Fig. 354) would be able to answer all his questions, but when he finally debated with him on these issues, he discovered that, although he was very eloquent in his speech, his words on astronomy were vacuous:

My first testing of him showed a man untested in the arts and sciences. [He was] ignorant in the arts and sciences in which I had expected him to excel. [Yet] he realized [this knowledge] was beyond him, and he was not ashamed to testify to the fact. […] He was not too ignorant to see his own ignorance.

Shortly thereafter, Augustine obtained a position in Milan, working in close association with Saint Ambrose (340–397), a talented bishop more powerful than any of the weak popes of his day. He soon discovered that Ambrose did not read the Bible literally where it contradicted reason. This pleased Augustine, yet he also realized Ambrose’s claims were not as certain as “my certainty that three and seven make ten.”

Around this time, Augustine also began to read the Neo-Platonists, which gave him a more sophisticated conception of God. According to the Neo-Platonists, God was not a vast physical being (as the Manichaeans claimed), but being itself. The Neo-Platonists also believed that God was perfectly good and that evil did not have any true material existence. These concepts gave him a more sophisticated way of articulating Christian beliefs. As a result, his intellectual doubts about Christianity vanished. Following the Neo-Platonic idea to find God within, Augustine had his first mystical experience:

The book of the Platonists did provoke in me a return into myself. You guiding, I entered my own recesses, though only you [God], helping me, made that possible. Entered there, I could see, so far as I could see anything with my poor soul’s vision, something beyond my soul’s vision, and beyond my mind, an always unfailing light.

He equated this unfailing light with God and truth.

But eventually, the intensity of his insight subsided. He then realized he could not sustain this insight by himself and needed to accept Christ as a mediator to support him. Until that point, he had seen Jesus as “only a man,” but now he began to see him as “the walking truth.”

His lustful feelings were also still present, and since he could no longer blame his reluctance of faith on his intellectual uncertainty, he knew he had to face it once and for all. When hearing about the life of the Egyptian hermit Saint Anthony, who had actually put into practice what the Church Fathers had only intellectually speculated about, he knew his own efforts had not been strong enough. In the most famous passage of The Confessions, he wrote:

I in my great worthlessness [...] had begged you for chastity, saying, “[God], grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.” I was afraid that you would hear my prayer too soon, and too soon would heal me from the disease of lust which I wanted satisfied rather than extinguished. [180]

After this realization, he finally broke down and let it all out:

I went into myself, and what complaints against myself did I not raise? With what verbal reverberations I lashed my soul, trying to force it along with me in my quest for you. But it resisted, it would not move, though it could not excuse itself—all its arguments had run out, had been refuted. […] I went to Alypius [his best friend] with storm on my face and in my mind, and burst out: What is the matter with us? […] Did you hear that story [of Saint Anthony]? Non-philosophers surge ahead of us and snatch heaven, while we, with our cold learning […], are still mired in flesh and blood.

Augustine and Alypius then withdrew to a garden to let his experience play out.

By looking thus deep into myself I dragged from my inmost hiding places an entire store of pitiable memories and laid them out for my heart to see. A vast storm hit me at this point, and brought great sheets of showering tears. […] How much more, Lord, how much more will this go on? Will you be forever angry, Lord, and never cease? […] I felt still in the grip of those vices, and I blubbered pitiably: How long, how long—on the morrow is it, always tomorrow? Why never now? Why does this very hour not end all my vileness?

And then it happened. He suddenly heard a child’s voice saying, “Take up and read” (“Tolle, lege”):

I heard from a nearby house the voice of a boy—or perhaps a girl, I could not tell—chanting in repeated singsong: “Take up and read.” My features relaxed immediately while I studied as hard as I could whether children use such a chant in any of their games. But I could not remember ever having heard it. No longer crying, I leaped up, not doubting that it was by divine prompting that I should open the book and read what first I hit on. I rushed back to where Alypius was sitting, since I had left the book of the Apostle when I moved away from him. I grabbed, opened, read: “Give up indulgence and drunkenness, give up lust and obscenity, give up strife and rivalries and clothe yourself in Jesus Christ the Lord, leaving no further allowance for fleshy desires.” The very instant I finished that sentence, light was flooding my heart with assurance, and all my shadowy reluctance evanesced. [179]

After that moment, Augustine turned away from sex and was baptized by Saint Ambrose along with Alypius and his son. Eventually, he became bishop of Hippo, a city in Algeria. In 430, as Augustine lay dying in Hippo, the barbarian Vandals were besieging the city. They captured the city soon after his death.

Fig. 355 – The conversion of Augustine by Fra Angelico (c. 1430) (Musée Thomas-Henry, France)

Original sin

The theological stance of Augustine that most impacted Western civilization—for better or worse—concerned free will. Augustine worked out his ideas on the matter in response to the theologian Pelagius (c. 354–418). Pelagius had claimed that all just people would reach heaven and that infants were without sin. Augustine objected to both points, claiming Pelagius had a naive understanding of the gravity of sin. Instead, Augustine asserted that each of us has inherited sin through Adam’s fall in the Garden of Eden, which he identified as the “original sin.” Adam’s sin had corrupted humanity, weakening its free will. Anyone who did not feel this darkness within himself, he claimed, simply had not done enough soul searching. The New Testament comes closest to this idea in the writings of Paul, who claimed sin and death were brought into the world through Adam’s fall, but he did not go as far as to infer that we all carry inherited sin, irrespective of our actions in life.

According to

Augustine, our will has become so weak that we will never achieve salvation

on our own. God is simply too great and we too small. Instead, our salvation

is entirely dependent on the grace of God. Those who are damned have

only themselves to blame (given the little free will we have left), yet any

person saved is entirely due to God. In some cases, he was even more

fatalistic, claiming God had already decided since the beginning of time whom

he would save and whom he would damn.