Inspired by Arabic love poems, the troubadours of France and the minnesingers of Germany began to celebrate their love for their Lady with close to religious devotion. Despite condemnation by the Church, these medieval poets began to shun loveless arranged marriages in favor of affairs with partners of their own choosing. To them, earthly love for a woman was neither a sin nor madness, but instead an ennobling pursuit.

The most famous love story of the Middle Ages was between the great Scholastic philosopher Pierre Abelard (whom we met before) and the talented female intellectual Heloise. Abelard had a remarkably sharp and modern mind. Like the Roman philosophers he admired, he had a strong trust in his power to understand the world through reason. He applied this even when it concerned matters of faith, which often got him in trouble with the authorities. He also wrote one of the first proper autobiographies in world history, in which he expressed his personal thoughts with surprising honesty and comfort. His ability to share his inner world—for its own sake—became one of the hallmarks of Western civilization. Using both his autobiography and a series of love letters that have come down to us, we will discuss their story.

A short history of love

In the modern West, a man and a woman ideally find each other through love and eventually seal their bond through marriage. This view, however, is rare in history. Although marriage of some sort has existed in virtually all cultures in history, it was usually arranged by the parents for social, economic, and political reasons, and often with a large age difference between the two partners. Of course, love can blossom in these relationships, but this is not the norm.

Throughout Western history, philosophers and theologians were generally dismissive of love, which they considered to be a form of madness. Plato did find a use for love, believing that love for a specific person could serve as a stepping stone towards experiencing the Form of beauty. Surprisingly, the Greek philosophers often referred to homosexual love in these contexts, considering love between a man and woman less important. Aristotle had a more modern view, seeing human beings as “social animals” who bond through love. He saw friendship, and not marriage, as the ultimate form of love. True friends, he claimed, wish each other well for their own sake. They are to us like a “second self.” [231]

The Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius (c. 15–55 BC) saw love solely as a natural drive for procreation and pleasure. Sexual desire, in his view, was both addictive and never fully satisfied. Avoiding it, he claimed, was no realistic option, as deprivation causes our brain to torment itself with fantasies. His solution was moderation. Ovid (c. 43 BC–18 AD), another Roman poet, shared Lucretius’s biological view of sex but was more optimistic. He saw love as a game that one could learn to get good at. His book The Art of Love is one of the earliest dating manuals of the West, giving tips on how to seduce women. Similar to modern pickup artists, he gave advice such as “The theatre’s curve is a very good place for your hunting” and “Women can always be caught; that’s the first rule of the game.” [232]

In the Judeo-Christian tradition the word love was mostly reserved for the dispassionate love for one’s neighbors and the love of God. The love of God entailed an unconditional submission to his will, sometimes combined with a fear of his awesome power (to be “God-fearing” was a virtue in the Old Testament).

In the Arabic world, an Islamic sect called Sufism championed yet another type of love. The ultimate goal of the Sufis was to dissolve themselves in the divine through their love, famously allegorized by a moth attracted by and then dissolved by a flame. A famous Sufi called al-Bastami (ninth century) wrote about this state of mind: “God speaks with my tongue and I have vanished.” About his union with God, he said: “Lover, beloved, and love are one!” and “I am the Wine-drinker, the Wine, and the Cupbearer!” [233]

The Arabic world of the ninth century also gave rise to a rich tradition of secular love poetry, in which love, pleasure, and the drinking of wine were celebrated for their own sake. In these works, we read of the plight of unrequited love, secret love, love which persists against many obstacles, and the idea of love as both a sickness and a medicine, as torment and delight.

The troubadours

These ideas would spread to Moorish Spain in the 10th and 11th centuries, where they became the main influence for the troubadours. The troubadours resisted arranged marriages and instead popularized the notion of being with the woman of their own choosing. This idea was further developed during the Enlightenment, but it wasn’t until the 19th century that it became part of the general culture, likely because the growing prosperity of the Industrial Revolution made economic considerations for marriage less important.

We have a plausible story for how the Arabic tradition of love poetry entered France. After William VIII (c. 1025–1086), the Duke of Aquitaine, waged war against a Muslim-ruled city in Northern Spain, he managed to take home hundreds of prisoners, including a number of musicians and their instruments. William’s son, William IX (1071–1126), was inspired by their music and became the first troubadour.

The troubadours wrote poems in which they celebrated refined love (fin amor) for a Lady—the capital “L” used for women of royal descent. True love, they claimed, ennobles the lover, as it pushes them to do good and courageous deeds to impress their Lady. As a result, they saw love as a school in virtue. In the words of Guiraut Riquier (1254–1292):

Noble and true and more constant than usual, am I towards love for my Fair Delight [...], for this I love nobly, that by loving I am enhanced. [...] Love causes all good deeds to be done and bestows those qualities that are worthy. Thus love is a school of valor, [as] love guides him to valorous port. [234]

Without this refined love, they believed, people would miss out on one of the greatest joys in life. In the words of Bernart de Ventadorn (1135–1194), who entered the service of Eleanor of Aquitaine (the granddaughter of William IX):

Any man is indeed of base life who has not his dwelling with joy and who directs not towards love his heart and his desiring, since all that is […] rings and is full of song: Meadows and parklands and orchards, heathlands and plains and woods. [235]

But besides being a source of joy and virtue, love could also bring on pain and madness in the form of lovesickness. There is an account—though hopefully fictional—of a troubadour who bought a leper’s gown and mutilated his finger just to be able to sit amongst the sick in front of his Lady’s door to await her alms. Equally disturbing, the poet Peire Vidal (12th century) was said to have sewn himself into the skin of a wolf in honor of a Lady named La Loba (“The She-Wolf”). The plan went horribly wrong when he provoked a shepherd’s dog, which almost killed him. Afterward, the Lady and her husband, laughing together, took care of him until he was well. Similarly, in literature, we read that Sir Lancelot ran like a lunatic in the woods for months, not knowing how to deal with his love for Guinevere. This duality of the pain and joy of love is beautifully expressed in the words of William IX:

For joy of her a sick man can be cured, and from her anger a healthy man can die, and a wise man go mad, and a handsome man lose his good looks, and the most courtly one become a boor, and the totally boorish one turn courtly. [236]

Fig. 406 – A song by Guiraut Riquier (13th century) (Bibliotheque Nationale de France)

According to Bernart de Ventadorn, rejection could even feel like death:

Since nothing can help me with my Lady, neither prayers nor grace, nor the rights that I have. Since it does not please her that I love her, I shall not speak of love again. I give up love and deny it. She has willed my death, and I answer with death. I leave, since she does not hold me back, and go wretched into exile, not knowing where. [237]

Fig. 407 – Troubadours playing music, from the Cantigas de Santa Maria (1250 AD)

Since most girls were already locked in marriage from a young age, the troubadours saw no choice but to declare marriage the enemy and to celebrate adultery. Andreas Capellanus (12th century), in his work De Amore, referred to a curious judgment passed by the female-staffed court of the countess of Champagne on this issue:

We declare and hold as firmly established that love cannot exert its powers between two people who are married to each other. For lovers give each other everything freely, under no compulsion or necessity, but married people are in duty bound to give in to each other’s desires and deny themselves to each other in nothing. [238]

According to Andreas, this court ruling was later used as a precedent in the court of Eleanor of Aquitaine. A woman had promised to be with a man if she would ever fall out of love with her future husband. When the two got married, the man argued that he was entitled to be with her, claiming that marriage and love were mutually exclusive. According to Andreas, Eleanor ruled in his favor based on the decision by the countess of Champagne.

To the Church, however, adultery was one of the gravest sins, for which harsh punishments were inflicted by the law courts and for which burning in eternal hellfire was reserved in the afterlife. The Church warned against the temptations of women, often citing Eve’s temptation of Adam in the Garden of Eden, causing Adam to commit the original sin. From the beginning of time, the Church claimed, women had been a source of wickedness.

With husbands, the Church, and the government on the lookout, lovers had to meet in secret. If they spent the night together, they had to depart before sunrise—sometimes at the warning of a watchman—before the Lady’s jealous spouse discovered them. Take, for instance, the following anonymous poem:

In an orchard, under a hawthorn tree, by her side the Lady clasps her lover, till the watchman calls that dawn has appeared. O God! O God! This dawn! How quickly it comes! [239]

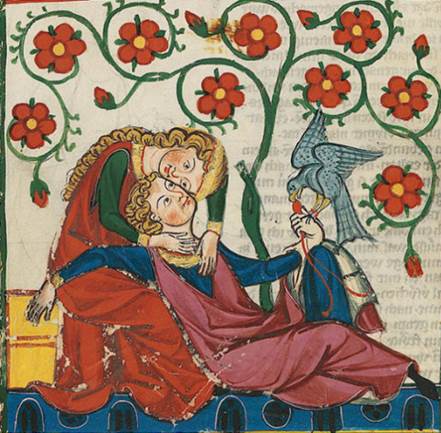

Fig. 408 – Two images from the Manesse Codex (c. 1305 AD) (University Library Heidelberg, Germany)

Despite all their talk about the pursuit of women, it might surprise you that sex often wasn’t the end goal for the troubadours. They regarded sexual possession as crude compared to the ethical and spiritual enrichment that came from being in love. Some even preferred to admire a woman from afar or spoke of their love for a Lady they had never even seen, such as a princess in a distant land. Others, however, clearly had sex in mind. Arnaut Daniel (12th century) wrote that he hoped “she [would] let me, secretly, into her bedroom!” William IX, a true ladies’ man, once said, “God let me live long enough to get my hands under her cloak!” A biographer from the 13th century wrote about him:

The count of Poitou was one of the most courtly men in the world as well as one of the greatest deceivers of ladies, and a fine knight in deeds of arms, and generous in wooing; and he knew well how to compose and sing. And he traveled for a long time throughout the world in order to deceive ladies. [240]

The tradition of the troubadours also spread to Germany, where they came to be known as minnesingers (“singers of love”). Their leading master was Walter von der Vogelweide (c. 1170–1230), who said of love (minne) that “she comes never to a false heart.” [222] He also famously broke with the tradition that only noblewomen (“Ladies”) were worth writing about. He wrote:

Woman will be ever woman’s noblest name, greater in worth than Lady! [222]

In his most famous poem, we read of a man and a woman meeting in secret under a lime tree, written from the woman’s perspective:

Under the lime tree (“under der linden”) on the heather, where we had shared a place of rest, still you may find there, lovely together, flowers crushed and grass down-pressed. Beside the forest in the vale, “tandaradei,” sweetly sang the nightingale.

I came to meet him at the green. There was my true love come before. Such was I greeted—Heaven’s Queen!—that I am glad for evermore. Had he kisses? A thousand some, “tandaradei,” see how red my mouth’s become.

There he had fashioned for luxury a bed from every kind of flower. It sets to laughing delightedly whoever comes upon that bower. By the roses well one may, “tandaradei,” mark the spot my head once lay.

If any knew he lay with me (May God forbid!), for shame I’d die. What did he do? May none but he ever be sure of that—and I, and one extremely tiny bird, “tandaradei,” who will, I think, not say a word. [241]

Walter also rejected the traditional link between love and sin:

Whoever says that love is sin, let him consider first and well, right many virtues lodge therein with which we all, by rights, should dwell. [222]

Tristan and Isolde

In the 12th century, the adulterous love story of Tristan and Isolde became popular. Many versions of the story exist, but the best one was written in Germany by the poet Gottfried von Strassburg (d. c. 1210). Of special interest are Gottfried’s autobiographical comments, which appear in various parts of his book. In these passages, he shows his willingness to fully engage with his earthly life, accepting both its joys and sorrows, even at the possible expense of his place in heaven. We read:

I have undertaken a labor, a labor out of love for the world and to comfort noble hearts, those that I hold dear, and the world to which my heart goes out. Not the common world do I mean of those who (as I have heard) cannot bear grief and desire but to bathe in bliss. (May God then let them dwell in bliss!) Their world and manner of life my tale does not regard: its life and mine lie apart. Another world do I hold in mind, which bears together in one heart its bitter sweet, its dear grief, its heart’s delight and its pain of longing, dear life and sorrowful death, its dear death and sorrowful life. In this world let me have my world, to be damned with it, or to be saved. [222]

Whereas the standard Christian narrative calls us to reject the world in favor of heaven, Gottfried was willing to embrace life and accept it as a mix of both joy and sorrow (as indicated by his endless oxymorons). His willingness to place his love for a specific woman above the laws of the omnipotent God—even in the face of damnation—became a common theme in the West.

In his introduction, Gottfried introduced the story in the following memorable way:

When we are deeply in love, however great the pain, our heart does not flinch. The more a lover’s passion burns in its furnace of desire, the more ardently will he love. This sorrow is so full of joy, this ill is so inspiring that, having once been heartened by it, no noble heart will forgo it! I know as sure as death and have learned it from this same anguish: the noble lover loves love stories. Therefore, whoever wants a story need go no further than here. I will story him well with noble lovers who gave proof of perfect love: A man a woman, a woman a man, Tristan Isolt, Isolt Tristan.

[...] This is bread to all noble hearts. With this, their death lives on. We read their life, we read their death, and to us it is sweet as bread. Their life, their death, are our bread. [242]

The story starts with Rivalin, Tristan’s father, who was a powerful knight and king of Parmenie. In an attempt to defend his country, he was killed by a knight named Morgan, who took over his land. His wife heard the news while giving birth, which also caused her death. Just before she died, she named her son Tristan, from the word triste (sorrow), since he was born in such sorrowful circumstances. A friend of the family named Rual hid the orphan for fear that Morgan would kill him, as the newborn was the rightful heir to the throne.

At the age of seven, Rual placed Tristan under the care of an intelligent and trustworthy tutor named Curvenal. Together they traveled through Europe, where the boy learned to hunt and fight, and he also “spent many hours playing stringed instruments of all kinds.” Yet, at the age of fourteen, Tristan was abducted by merchants, who took him on their ship. At sea, heavy winds began to blow, and the ship lost control. The merchants, believing this to be an omen for their bad conduct, agreed to free Tristan. Once they regained control of the vessel, “the wind had beaten them to Cornwall,” in Britain, where they released him. Alone in unknown territory, Tristan cried and prayed for help. Not long after, he met a group of huntsmen who had just caught a boar. When they dismembered the boar improperly, Tristan decided to help them out. The hunters were impressed (“Are you versed in the art, boy?”) and invited him to ride with them to court. There, he met King Mark, who was very impressed by Tristan’s knowledge and his ability to play the harp. They became great friends. Mark even decided not to get married and to make Tristan his heir.

Then a man named Morold showed up, demanding tribute for the king of Ireland. Resisting this demand, Tristan challenged Morold to a duel. During the fight, Tristan was wounded by his enemy’s poisonous sword. Morold explained that the queen of Ireland could cure him in exchange for the tribute, but Tristan refused and killed Morold, leaving behind a splinter from his sword in his body.

To get cured, Tristan sailed to Dublin. Close to shore, he decided to let his boat float aimlessly on the waves. When a number of men found him in his boat, they heard “the sweet strains of his harp.” Tristan claimed he was a minstrel, sailing from court to court, who had been attacked by pirates. A priest recognized his brilliance and decided to take him to the queen. He introduced himself as “Tan-tris” to conceal his identity, and she agreed to cure him.

Back home, Tristan told King Mark about Isolde, the daughter of the queen, speaking very highly of her beauty. Jealous of Tristan’s claim to the throne, several barons at the court persuaded the king to take Isolde as his wife and produce a biological heir. “Heaven has given us a good heir,” replied the king. As they couldn’t convince Mark, they instead started to plot Tristan’s death. Full of fear, Tristan convinced Mark to fulfill their wishes. As a result, Mark decided to send Tristan back to Ireland to arrange the marriage.

The king of Ireland had vowed to offer his daughter in marriage to whoever was able to kill a dragon that plagued the land. Tristan took on the task and was successful, after which the king agreed to the marriage of Isolde and Mark. The queen also promised to protect Tristan while he was in Ireland. Before returning to Cornwall, Tristan took a bath, and Isolde kept looking at him with uncommon interest, but then she discovered that the splinter she had recovered from Morold’s body matched the piece missing from Tristan’s sword. She suddenly realized that Tan-tris was, in fact, Tristan. When she was about to kill him, her mother entered and reminded her of the promise she had made to protect Tristan in her land. Isolde couldn’t care less and lifted the sword, but she could not bring herself to kill him.

Fig. 409 – Tristan playing the harp for King Mark (left) and Tristan holding the love potion (right) from the Chertsey Abbey tiles (Roger Loomis)

The love potion

Before departure, the queen brewed a love potion and asked Isolde’s maid named Brangane to secretly add it to the wine of Isolde and Mark to ensure they would fall in love. On the ship back home, however, Tristan and Isolde accidentally drank the potion. When Brangane noticed what had happened, she picked up the flask and threw it into the sea:

‘‘That flask and what it contained will be the death of you both,” she said, and she told the two the whole tale. Tristan replied, “So then, God’s will be done, whether death it be or life! For that drink has sweetly poisoned me. What the death of which you tell is to be, I do not know, but this death suits me well. And if delightful Isolt is to go on being my death this way, then I shall gladly court an eternal death.” [222]

The potion also changed Isolde completely:

Isolde’s hatred was gone. They shared a single heart. The two were one in both joy and sorrow, yet they hid their feelings for each other. [242]

Brangane observed the couple “pining and languishing, sighing and sorrowing, musing and dreaming and changing color.” Tristan said, “I do not know what has come over poor Isolde and me, but both of us have gone mad in the briefest space of time with unimaginable torment.” Tristan, wanting to be loyal to the king, tried to constrain himself. “Honor and Loyalty harassed him powerfully, but Love harassed him more.” As a result, he and Isolde slept together.

Brangane advised the lovers to keep their love a secret. Back at Mark’s court, she was willing to switch places with Isolde during the night so that Mark would not notice that Isolde was no longer a virgin. The plan worked, for, to Mark, “one woman was as another.”

The endless lies and trickery had only begun. When a steward followed Tristan’s footsteps in the snow, he saw the couple together. The steward told King Mark, but the king fully trusted his good friend Tristan:

In his artlessness [meaning: naivety], Mark, the best and most loyal of men, was amazed and reluctant to agree that he should ever have Isolde under any suspicion of misconduct whatsoever. [242]

Adding to the tragedy, Mark was never presented as a villain in Gottfried’s version of the story. He was a noble man and a good friend who admired Tristan and “held him dear to his heart.”

The steward, wanting to prove himself right, kept plotting schemes to reveal their secret, but most of his plans backfired. At one point, he spread flour around Tristan’s bed to prove he left his bed at night. Brangane informed Tristan about the flour, but when Tristan attempted to leap over it, he popped open a vein (earlier, he had been bleeding himself, a common medical procedure in the Middle Ages). When Mark entered his room, he saw no trace on the floor, but the bed was full of blood. However, he was still unwilling to accept what he had seen. We read:

He had just found Love’s guilty traces in his bed and was thus told the truth and denied it. [242]

Yet, over time, Mark’s suspicions did grow and he began to keep an eye on them. He secretly read the truth in Isolde’s eyes many, many times, and finally he could not deny it any longer. He summoned them both and said to Isolde:

I am not such a fool as not to know or see from your behavior in public and in private that your heart and eyes are forever fixed on my nephew. You show him a kinder face than ever you show me, from which I conclude that he is dearer to you than I am. [...] But now I tell you how it is to end. I will bear with you no longer the shame and grief that you have caused me, with all its suffering. From now on I will not endure this dishonor! [...] Nephew Tristan, and my lady Isolde, I love you too much to put you to death or harm you in any way, loath as I am to confess it. [242]

However, since I now can see it in you both, that, despite my every wish, you love and have always loved each other more than me, then go, remain together as you will: have no further fear of me. Since your love is so great, I shall not, from this time forth, trouble or oppress you in any of your affairs. Take each other by the hand and depart from this court and land. For if I am to be wronged by you, I prefer not to see or hear of it. [...] So go, both of you, in God’s care! Go love and live as you please! Our fellowship is ended, here and now. [222]

The Grotto of Love

Leaving the court, Tristan took Isolde to a cave in the wilderness, called the Grotto of Love (“Die Minnegrotte”), which he had once stumbled upon during the hunt. We read:

The grotto had been hewn in heathen times into the wild mountain, when giants ruled [...]. And there they used to hide when they wished privacy to make love. Indeed, wherever such a grotto was found, it was closed with a door of bronze and inscribed to Love with this name: “La fossiure a la gent amant” (“The Grotto for People in Love”).

The name well suited the place. For as its legend lets us know, the grotto was circular, wide, high, and with upright walls, snow-white, smooth and plain. Above, the vault was finely joined, and on the keystone there was a crown, embellished beautifully by the goldsmith’s art with an incrustation of gems. The pavement below was of a smooth, shining, and rich marble, green as grass. In the center stood a bed, handsomely and cleanly hewn of crystal, high and wide, well raised from the ground, and engraved roundabout with letters which—according to the legend—proclaimed its dedication to the goddess Minne. Aloft, in the ceiling of the grotto, three little windows had been cut, through which light fell here and there. And at the place of entrance and departure was a door of bronze. [222]

The grotto resembled a Gothic cathedral but with the bed at its center instead of an altar. With this metaphor, Gottfried made earthy love divine. The grotto of the timeless goddess Minne, where the lovers could freely consummate their desires, was powerfully contrasted with Mark’s court, the worldly plane of society, order, loyalty, and honor. We read:

Then finally, it has meaning, as well, that the grotto should lie thus alone in a savage waste. The interpretation must be that Love and her occasions are not to be found abroad in the streets, nor in any open field. She is hidden away in the wild. And the way to her resort is toilsome and austere. Mountains lie all about, with many difficult turns leading here and there. The trails run up and down; we are martyred with obstructing rocks. No matter how well we keep the path, if we miss one single step, we shall never know safe return. But whoever has the good fortune to penetrate that wilderness, for his labors will gain a beatific reward. For he shall find there his heart’s delight. The wilderness abounds in whatsoever the ear desires to hear, whatsoever would please the eye; so that no one could possibly wish to be anywhere else.

Gottfried then adds another biographical note, in which he confesses—albeit in coded language—that he, too, had experienced “minne”:

And this I well know; for I have been there. I, too, have tracked and followed after the wild birds and beasts in that wilderness, the deer and other game, over many a woodland stream and yet passed my time and not seen the end of the chase. My toils were not crowned with success. I have found the lever and seen the latch in that cave and have, on occasion, even pressed on to the bed of crystal—I have danced there and back some few times. But never have I had my repose on it. [...] The little sun giving windows often have sent their rays into my heart. I have known that grotto since my eleventh year, yet never have I been to Cornwall. [222]

So, Gottfried’s grotto was not a literal cave. It was a metaphor for the consummation of divine love, which he described without any reference to the Christian God. Instead, the text claims the two needed nothing apart from each other, not even food and drink to sustain themselves.

Back at the court, Mark missed both his wife and his friend and decided to hunt to ease his pain. When Tristan heard the horns and dogs of the hunting party, he quickly placed a sword between himself and Isolde and pretended he was sleeping. When Mark stumbled upon the cave by accident and looked through the window, he was once again convinced the two had not slept together. To shield Isolde from the sun, dear Mark covered the window with grass and flowers. “He made the sign of the cross over the lovely woman in farewell, and went away in tears.”

Back home, Mark sent Curvenal to fetch Tristan and Isolde and bring them back to court. Once more, Mark had tricked himself against his better judgment into believing that order had been restored. But this wouldn’t last long. Isolde found a lonely place in an orchard, and she ordered a bed to be made there and asked Tristan to come over. But then Mark walked into the garden and found them there, asleep in each other’s arms:

He found his wife and his nephew tightly enlaced in each other’s arms, her cheek against his cheek, her mouth on his mouth. All that the coverlet permitted him to see—their arms and hands, their shoulders and breasts—was so closely locked together that, had they been a piece cast in bronze or in gold, it could not have been joined more perfectly. [Finally, Mark’s] overload of doubt and suspicion was gone—he no longer fancied, he knew. Mark left in silence and called for his counselors to act as proper witnesses. [242]

When Tristan woke up, he understood what had happened:

He means to have us killed! Dearest lady, lovely Isolde, we must part, and in such a way that chances of being happy together may never come our way again.

Isolde quickly offered him a ring as a witness to their enduring love, after which Tristan fled the scene just in time. He traveled from place to place, searching for a life that could relieve him of his sorrow. In Arundel, he met the knight Kaedin and his sister, Isolde of the White Hands, who reminded Tristan of his Isolde back home (from now on called Isolde the Fair). Believing Isolde the Fair had forgotten about him, Tristan decided to marry Isolde of the White Hands, but he managed to avoid sleeping with her, blaming an injury.

When Tristan was wounded by a poisonous spear, he needed Isolde the Fair’s help to cure him. Unable to travel in his condition, he told Kaedin his secret and asked him to bring Isolde over. He asked him to return with a white sail if he managed to bring Isolde along and to use a black sail if she could not come (a motif borrowed from the Greek myth of Theseus). What he did not know, however, was that Isolde of the White Hands had overheard their conversation. When the ship arrived with a white sail, she told Tristan that the sail was black. Upon hearing this, he felt the greatest pain he had ever felt.

Since you will not come to me I must die for your love. I can hold on to life no longer.

Three times, he uttered the words “dearest Isolde,” and at the fourth, his spirit left him. When Isolde reached the shore, she heard great laments among the villagers:

My lady, as God help me, we have greater sorrow than people ever had before. Gallant, noble Tristan, who was a source of strength to the whole realm, is dead!

This news struck Isolde with grief. She went to see his body and prayed for him:

Tristan, my love, now that I see you dead, it is against reason for me to live longer. You died for my love, and I, love, die of grief, for I could not come in time to heal you and your wound. Had I arrived on time, I would have given you back your life and spoken gently to you of the love there was between us. If I had failed to cure you, we could have died together. But since I could not come in time and found you dead I shall console myself by drinking of the same cup. You have forfeited your life on my account, and I shall do as a true lover: I shall die for you in return.

She took him in her arms, kissed his face and lips, and clasped him tightly against her. Then, straining body to body, mouth to mouth, she at once gave up her spirit out of sorrow and died at his side.

Abelard and Heloise

In the second half of this chapter, we will discuss the most famous love story of the Middle Ages, between the great Scholastic philosopher Pierre Abelard (1079–1142) and the talented female intellectual Heloise (c. 1100–1164). Abelard wrote their story down in an autobiography, a rare genre at the time.

In what follows, we will discuss his life and his encounters with Heloise. But first, let’s place his work in its proper context. In Late Antiquity, Saint Augustine had written his marvelous introspective work, The Confessions, but after the fall of Rome, Europe lost interest in subjective human experience for centuries. This all changed when Abelard published his Historia Calamitatum (The History of My Misfortunes). Abelard wrote this autobiography in a surprisingly confident style. He was openly arrogant and proud of his intellectual and personal exploits and also bluntly honest about his failings, his shameful moments, and even his affair with a young female scholar named Heloise. He also presents himself as a strong debater who demanded reason in his arguments, even when it concerned matters of faith. In all these aspects, he easily matches up with the great Renaissance writers, putting him centuries ahead of his time.

The history of my misfortunes

Abelard was a successful theologian, respected by many, but he also made countless enemies as he could not keep his controversial opinions to himself. At the age of about twenty, he went to Paris to study logic at the great cathedral school of Notre-Dame de Paris (this was before the current cathedral was built). It wouldn’t take long for him to defeat his teacher of logic, William of Champeaux, in argument. We read:

I brought him great grief, because I undertook to refute certain of his opinions, not infrequently attacking him in disputation, and now and then in these debates I was adjudged victor. Now this, to those among my fellow students who were ranked foremost, seemed all the more insufferable because of my youth and the brief duration of my studies. [215]

Not long after, and against the will of his teacher (and with the help of some of William’s powerful rivals), Abelard started his own school in the nearby town of Melun, stealing many students from his former master. Abelard continued to hold disputes with his former master, embarrassing him even more:

In the course of our many arguments on various matters, I compelled him by most potent reasoning first to alter his former opinion on the subject of the universals, and finally to abandon it altogether. Thus, it came about that my teaching won such strength and authority that even those who before had clung most vehemently to my former master, and most bitterly attacked my doctrines, now flocked to my school.

When William eventually stepped down from his position to become a hermit, his successor offered up his place to Abelard and became his student, making him master of the Notre Dame. This delighted Abelard and made his former teacher extremely jealous:

[When] my master saw me directing the study of dialectics there, it is not easy to find words to tell with what envy he was consumed or with what pain he was tormented.

As revenge, William used his authority to remove Abelard from his position and replaced him with one of his rivals. Abelard then returned to his own school in Melun.

At the age of 34, Abelard sought out William’s former teacher of theology, Anselm of Laon, but Anselm also failed to meet Abelard’s expectations. Ruthless in his criticism, Abelard wrote about him:

[His] fame, in truth, was more the result of long-established custom than of the potency of his own talent or intellect. If anyone came to him impelled by doubt on any subject, he went away more doubtful still. [...] He had a miraculous flock of words, but they were contemptible in meaning and quite void of reason. When he kindled a fire, he filled his house with smoke and illumined it not at all. He was a tree which seemed noble to those who gazed upon its leaves from afar, but to those who came nearer and examined it more closely was revealed its barrenness. When, therefore, I had come to this tree that I might pluck the fruit thereof, I discovered that it was indeed the fig tree which Our Lord cursed [referring to Jesus cursing a fig tree in the New Testament].

As a result, Abelard regularly skipped classes, which offended some of Anselm’s students. When they inquired about his absence, he responded that he believed “educated people” should be able to “understand the sacred books simply by studying them themselves [...] without the aid of any teacher.” His rivals mocked him for this opinion, especially since he had barely started his study of theology. They challenged him to interpret one of the most obscure prophecies of Ezekiel. Abelard accepted the challenge and offered to lecture on the topic the next day. His rivals suggested that he might need more time for such a tough piece, but Abelard insisted he wanted to show his success “not by routine, but by ability.” Only a few students actually showed up, but those who did were impressed by his lecture and spread their praise around. Emboldened by this, he continued lecturing on scripture and attracted quite a crowd. This caused much jealousy, and eventually, he was not allowed to continue. All this opposition, however, “did not save to make [him] more famous.”

Darker thoughts

After a while, Abelard returned to his own school, which grew significantly in size because of his lectures. His wealth and fame, however, made his mind think of “darker thoughts.” We read:

Thus I, who by this time had come to regard myself as the only philosopher remaining in the whole world, and had ceased to fear any further disturbance of my peace, began to loosen the rein on my desires, although hitherto I had always lived in the utmost continence. And the greater progress I made in my lecturing on philosophy or theology, the more I departed alike from the practice of the philosophers and the spirit of the divines in the uncleanness of my life. [...] I had diligently kept myself from all excesses and from association with the women of noble birth who attended the school [and] I knew so little of the common talk of ordinary people.

It was during this period that he came to know Heloise:

Now there dwelt in that same city of Paris a certain young girl named Heloise, the niece of a canon who was called Fulbert. Her uncle’s love for her was equaled only by his desire that she should have the best education which he could possibly procure for her. Of no mean beauty, she stood out above all by reason of her abundant knowledge of letters. [...] It was this young girl whom I, after carefully considering all those qualities which are commonly to attract lovers, determined to unite with myself in the bonds of love, and indeed the thing seemed to me very easy to be done. So distinguished was my name, and I possessed such advantages of youth and comeliness, that no matter what woman I might favor with my love, I dreaded rejection of none.

When they met, Abelard was about 38 years old, and Heloise was only about seventeen. As a way to get close to her on a daily basis, Abelard convinced Fulbert to take him into his household as her teacher. Fulbert was thrilled with the idea that the great theologian Abelard would be teaching his niece. Abelard, however, misused his trust:

By his own earnest entreaties, he fell in with my desires beyond anything I had dared to hope, opening the way for my love; for he entrusted her wholly to my guidance, begging me to give her instruction whensoever I might be free from the duties of my school, no matter whether by day or by night, and to punish her sternly if ever I should find her negligent of her tasks. [...] I should not have been more smitten with wonder if he had entrusted a tender lamb to the care of a ravenous wolf.

Under the pretext of study, we spent our hours in the happiness of love. [...] Our speech was more of love than of the book which lay open before us; our kisses far outnumbered our reasoned words. Our hands sought less the book than each other’s bosoms; love drew our eyes together far more than the lesson drew them to the pages of our text. [...] No degree in love’s progress was left untried by our passion.

As this passionate rapture absorbed me more and more, I devoted ever less time to philosophy and to the work of the school. Though I still wrote poems, they dealt with love, not with the secrets of philosophy. Of these songs you yourself well know how some have become widely known and have been sung in many lands, chiefly by those who delighted in the things of this world.

In time, more and more people understood what was going on, except for Fulbert himself.

The truth was often enough hinted to him, and by many persons, but he could not believe it, partly, as I have said, by reason of his boundless love for his niece, and partly because of the well-known continence of my previous life.

At some point, however, he found out:

How great was the uncle’s grief when he learned the truth, and how bitter was the sorrow of the lovers when we were forced to part! With what shame was I overwhelmed [...]. Each grieved most, not for himself, but for the other.

But things were about to get even more complicated since Heloise discovered she was pregnant. When Abelard heard the news, he took her away from her uncle’s house and left for the countryside, where they remained until she gave birth. They gave their son the unusual name Astrolabius, after a scientific device used to measure the position of stars.

Abelard then returned to Paris, leaving his son with his sister (a common practice at the time). Back in Paris, he had to confront Fulbert and explain what had happened:

I went to [Fulbert] to entreat his forgiveness, promising to make any amends that he himself might decree. I pointed out that what had happened could not seem incredible to anyone who had ever felt the power of love, or who remembered how, from the very beginning of the human race, women had cast down even the noblest men to utter ruin. And in order to make amends even beyond his extremest hope, I offered to marry her whom I had seduced, provided only the thing could be kept secret, so that I might suffer no loss of reputation thereby. To this, he gladly assented.

In a letter to Abelard, we read that Heloise was opposed to the marriage, concerned for the disgrace it would bring upon Abelard and the damage it would do to his career as a man of the Church:

What penalties, she said, would the world rightly demand of her if she should rob it of so shining a light! What curses would follow such a loss to the Church, what tears among the philosophers would result from such a marriage!

She then went on to quote philosophers and Church Fathers who had warned of the endless disturbances of married life. She wrote:

What man, intent on his religious or philosophical meditations, can possibly endure the whining of children? [...] Who can endure the continual untidiness of children? [...] For this reason the renowned philosophers of old utterly despised the world [...] and denied themselves all its delights in order that they might repose in the embraces of philosophy alone.

With limitless devotion to Abelard, she concluded:

[It] would be far sweeter for her to be called my mistress than to be known as my wife and that this would be more honorable for me as well.

Fig. 410 – Abelard and Heloise discuss love and marriage, from The Roman de la Rose. Heloise is depicted as a nun. The two lines above the image translate to “How Peter Abelard instructs Heloise.” (14th century) (Musee Conde, France)

But Abelard’s mind was set on marriage. He wrote:

Because she could not bear to offend me, with grievous sighs and tears she made an end of her resistance, saying: “Then there is no more left but this, that in our doom the sorrow yet to come shall be no less than the love we two have already known.’’

Heloise also predicted that Fulbert would not keep their marriage a secret, and as it turned out, she was right. Fulbert started to spread the story, telling people his nephew-in-law was the famous Abelard. Heloise denied the story, and in response, her uncle visited her repeatedly with punishments. When Abelard heard of this, he immediately sent her to a nunnery. She protested but finally obeyed his wishes. To make matters worse, Fulbert had misinterpreted what had happened. He thought Abelard had sent her to the nunnery to get rid of her. In response, Fulbert had him castrated:

They cut off those parts of my body with which I had done that which was the cause of their sorrow.

To Abelard, the disgrace was worse than the physical pain, and he couldn’t help but think that God had punished him “in that very part of my body whereby [he] had sinned.” The event drove him to seek seclusion as a monk in the Abbey of Saint-Denis (which turned into the first Gothic cathedral near the end of his life).

Yes and no

It didn’t take long for Abelard to also turn his fellow monks into enemies. As a result, he left the monastery and moved to a hut, where he resumed his teaching. After a short while, many students showed up to hear him speak, causing nearby schools to lose a great number of students. This made his competitors jealous, causing them to file charges against him with the complaint that he studied secular works while living a monastic life and that he taught theology without ever having been educated in the subject. The content of his books also led to controversy. Around this time, he had written a work called Sic et Non (“Yes and No”), in which he juxtaposed contradictory quotations from the Bible and the Church Fathers (for more, see the chapter “The Philosophers’ Stone”). As one might imagine, this work hovered on the brink of heresy.

The real controversy, however, came when he wrote a tract on the unity and trinity of God, called Theologia Summi Boni in which he applied logic in matters of faith. Based on various quotations from this book, the Council of Soissons was summoned to investigate the legitimacy of his thoughts. Unfortunately, the chief instigators were the two jealous students from his old teacher Anselm. They slandered him so extensively that on his day of arrival, a crowd nearly stoned him. Yet, when the council actually studied his work, they couldn’t find anything heretical. Abelard asked the council for an opportunity to defend himself—giving him the opportunity to use his excellent debating skills—but the council, knowing full well they would not be able to defend their case in public, declined the offer. Behind closed doors, they condemned his book without further inquiry and ordered Abelard to burn it in public.

After casting his own book into a fire, Abelard was handed over to his former monastery, which was still filled with his enemies. Once there, he fanned the flames even more by casting doubt on the birthplace of their patron saint (two authoritative sources both named a different birthplace). In anger, they accused him of insulting the monastery and even the kingdom of France. A royal seneschal who examined the case concluded that the problem could be solved if the monastery would simply allow Abelard to leave, but they weren’t willing to because they benefited from his fame. However, when the seneschal explained that keeping Abelard against his will would bring them in bad repute, they granted him permission to live “in whatever solitary place he wished.”

The Paraclete

With permission from his former monastery, Abelard became a hermit, building himself a simple cabin and oratory:

[I] built with reeds and stalks my first oratory in the name of the Holy Trinity—called the Paraclete [meaning “helper,” referring to the Holy Spirit]. No sooner had scholars learned of my retreat than they began to flock thither from all sides, leaving their towns and castles to dwell in the wilderness. [215]

His students were very helpful, supplying him with whatever food and clothing he needed, and they even paid to rebuild his oratory in wood and stone. He taught there between 1122 and 1127.

Not long after, Abelard made his most famous enemy, Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), who was a strong opponent of the Scholastic method. Fearing he could be dragged in front of another council at any moment, Abelard fled to the abbey of Saint Gildas all the way in Brittany, where he didn’t even speak the language. The monks there were “vile and untamable” (they even had concubines). He made some attempts to reform the monastery, but he was unsuccessful. Instead, he quickly made new enemies, who, on one occasion, even tried to poison him. Luckily, another monk ate from his plate first and immediately dropped dead. It was under these circumstances that he wrote his autobiography, while “lamenting the uselessness and the wretchedness of [his] existence.”

A year later, at the age of 54, Abelard finally felt safe enough to return to Paris to teach at his school. This is where the famous scholar John of Salisbury (d. 1180) met him. John attended his lectures in 1136 and described him as “famous” and “admired by all.” Meanwhile, the Abbey of Saint-Denis had taken possession of Heloise’s nunnery and expelled all the nuns. Abelard invited the nuns to stay at the Paraclete and offered the place to Heloise as a gift. By this time, Heloise had taken charge of the nuns and had earned enormous respect for her religious zeal, good judgment, and patience. Unlike Abelard, she had also established strong diplomatic and legal relations with her neighbors.

Heloise

So far, we have mostly drawn from Abelard’s own description of what happened. Just after finishing his biography, a correspondence started between Abelard and Heloise, which gives insight into Heloise’s perspective. The first letter was written by Heloise, in response to her reading a copy of his autobiography. In this letter, she complained that he had rarely contacted her since she had become a nun. We read:

Tell me one thing. Why, after our conversion [to monastic life], commanded by thyself, did I drop into oblivion, to be no more refreshed by speech of thine or letter? Tell me, I say, if you can, or I will say what I feel and what everyone suspects: desire rather than friendship drew you to me, lust rather than love. So when desire ceased, whatever you were manifesting for its sake likewise vanished. This, beloved, is not so much my opinion as the opinion of all. [...] When little more than a girl I took the hard vows of a nun, not from piety but at your command. If I merit nothing from thee, how vain I deem my labor! I can expect no reward from God, as I have done nothing from love of Him. [...] God knows, at your command I would have followed or preceded you to fiery places. For my heart is not with me, but with thee. [243]

Abelard didn’t even give her much attention when they were together at the Paraclete, but despite everything, Heloise still loved him. Thinking back to their early days, she wrote:

There were in you two qualities by which you could draw the soul of any woman, the gift of poetry and the gift of singing, gifts which other philosophers had lacked. As a distraction from labor, you composed love-songs both in meter and in rhyme, which for their sweet sentiment and music have been sung and resung and have kept your name in every mouth. Your sweet melodies do not permit even the illiterate to forget you. Because of these gifts, women sighed for your love. And, as these songs sang of our loves, they quickly spread my name in many lands, and made me the envy of my sex. What excellence of mind or body did not adorn your youth?

You know, dearest—and who knows not?—how much I lost in you, and that an infamous act of treachery robbed me of you and of myself at once. [...] Love turned to madness and cut itself off from hope of that which alone it sought, when I obediently changed my garb and my heart too in order that I might prove you sole owner of my body as well as of my spirit. God knows, I have ever sought in you only thyself, desiring simply you and not what was yours. I asked no matrimonial contract, I looked for no dowry; not my pleasure, not my will, but yours have I striven to fulfill. And if the name of wife seemed holier or more potent, the word mistress was always sweeter to me, or even—be not angry!—concubine or harlot; for the more I lowered myself before you, the more I hoped to gain your favor, and the less I should hurt the glory of your renown.

I call God to witness that if Augustus, the master of the world, would honor me with marriage and invest me with equal rule, it would still seem to me dearer and more honorable to be called your whore than his empress. He who is rich and powerful is not the better man: that is a matter of fortune, this of merit. And she is venal who marries a rich man sooner than a poor man, and yearns for a husband’s riches rather than himself. Such a woman deserves pay and not affection. She is not seeking the man but his goods, and would wish, if possible, to prostitute herself to one still richer. [243]

Many passages show the purity of her love:

At every stage of my life up to now, as God knows, I have feared to offend you rather than God, and tried to please you more than him. [244]

Abelard’s answers fell short. In his biography, he had already admitted that his motivation for being with her had been mostly lust. In the fourth letter, he also confessed to having sent Heloise to the nunnery after his castration in part because he was jealous and wanted no other man to have her. When Heloise asked him to come live with her at the Paraclete, he responded in a distant and formal style, stating that this would be scandalous, since the two had been divorced by the knife and Heloise had become a bride of Christ. In response, Heloise wrote that Abelard would always remain her husband, whatever happened. In fact, she claimed that it was time for their real marriage to begin now that sexual fulfillment was no longer possible. It was time to launch their joint career as practicing intellectuals. But when he declined once more, Heloise finally accepted his refusal. Later correspondence moved past their personal issues and focused on theology and their monastic institution. Abelard helped Heloise by writing a set of rules for the nunnery, some letters of spiritual and institutional direction, and a number of hymns.

Condemnation

In 1140, Abelard faced a challenge that put an end to his teaching career. Several theologians, including Bernard of Clairvaux and William of Saint-Thierry, accused him once more of heretical thought. William had read Abelard’s works and concluded that his teachings corrupted faith and endangered the Church. What offended them were not just his theological positions, but also his method of shamelessly questioning authorities and pointing out contradictions:

Truly that man loves to question everything, wants to dispute everything, divine as well as secular. [213]

In his Disputatio adversus Petrum Abaelardum, William quoted the passages he found offensive and contradicted them—in an attempt to defeat Abelard at his own game. In another document, also likely by his hand, he accused Abelard of “treating the attributes of God not catholically but philosophically.” [213] Bernard used both works for his own treatise on the matter. His main complaint was that Abelard had applied logic where it was not applicable. Feeling under threat, Abelard pressured Bernard to either withdraw his accusations or to attend the Council of Sens to discuss the matter publicly. Bernard was initially reluctant, stating:

I refused because I am but a child in this sort of warfare and he is a man habituated to it from his youth, and because I believe it an unworthy deed to bring faith into the arena of controversy. [213]

Bernard finally agreed with Abelard’s request, but behind the scenes he convinced the attending bishops to condemn a list of Abelard’s heresies beforehand. When the council started, Abelard was given the opportunity to defend himself against the condemnation, but with everyone against him, he decided to leave the council and instead take up the matter with the pope in hopes of a fairer hearing (Abelard had powerful friends at the papacy whom he believed might be able to help him out). But this was a huge miscalculation. Bernard had already sent his critique to the pope and asked him to condemn the work and impose silence on Abelard. The pope agreed, excommunicating both Abelard and his followers. Abelard was also forced to enter a monastery and his books were to be burned.

One of his old students, Peter the Venerable (c. 1092–1156), managed to persuade the pope to lower his sentence. Peter, who was abbot of the Cluny monastery, the largest building in Europe, convinced the pope that Abelard could stay with him as long as he abandoned teaching. His excommunication was also retracted, allowing him to receive the eucharist.

Not long after, Abelard’s health began to fail. In a letter from Peter the Venerable to Heloise, Peter tells her about the last months of his life. We read that “as much as his illness permitted, he renewed his former studies and was always bending over his books,” always “praying or reading or writing or dictating.” He finally died in 1142, at the age of 63, uttering his last words, “I don’t know.” Peter the Venerable wrote the following epitaph, praising him as among the greatest thinkers of the world:

The Socrates of the Gauls, the greatest Plato of the West, our Aristotle, peer or superior to all other logicians, […] best of all in the force of reason and the art of speaking was Abelard. […] Through his long striving, At the end of his life, he won hope of a place with God’s philosophers. [245]

At Heloise’s request, Peter sent his

remains to the Paraclete for burial. When Heloise died about twenty years

later, she was buried there with him. In 1804, their bones were brought to the

gardens of the Elysee Palace, where Napoleon and Josephine paid tribute to

them. In 1817, the remains were brought to their latest resting place, the

Pere-Lachaise Cemetery. The Paraclete and its monastic community lasted until

the French Revolution.