The Renaissance began in the 14th century with the poet and philosopher Petrarch, the founder of humanism. Already in his formative years, he read the ancient texts of Rome not to gain a better understanding of the Christian God, but instead for their own sake, hoping to better understand the human condition. Later in his career, he discovered letters by his hero Cicero, providing an up-close and personal look into the life of one of the great geniuses of the Roman Republic.

Disappointed by his own era, he soon became determined to make a clean break with the medieval culture of his day, which he considered backward, uncritical, and out of touch with reality. Instead, he advocated for a return to the traditions of Greece and Rome, with its emphasis on reason, its artistic achievements, its focus on the citizen, and its interest in the human experience.

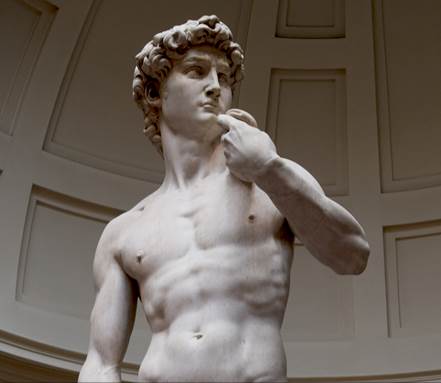

A century later, the humanists were confident enough to proclaim their era as a time of rebirth, or Renaissance. It would not take long until Renaissance Italy even surpassed their predecessors. In the arts, geniuses such as Michelangelo created paintings and sculptures of almost divine splendor. Instead of seeing human life as insignificant compared to the almighty God, he placed mankind at the center as the masterpiece of creation.

The Republic of Florence

It was only natural for the Renaissance to start in Italy. The Italians had always been surrounded by the ancient monuments of the Roman Empire, and urban life had survived the fall of Rome to a greater degree than anywhere else in Western Europe. When the great Renaissance poet Petrarch first visited Rome, he was “astonished by so many marvels” and was “overcome with wonder.” He remarked: “Rome was, in truth, even greater than I had thought, and the ruins even greater still. I wonder no longer why the world was dominated by this city.” [246]

In Italy, the run-up to the Renaissance had already started in the High Middle Ages. Inspired by ancient Rome, various cities turned into republics, which they called communes. By the early 12th century, these cities included Milan, Rome, Verona, Bologna, Siena, Pisa, Venice, and, most importantly, Florence. The Florentine republic originated in 1115 when the new merchant elite of Florence defeated both their Tuscan foreign rulers and their own aristocracy. They then transferred their power to a council known as the Signoria of Florence. The council consisted of nine guild members, who were selected by lot every two months. Although still excluding women, Florence became a relatively just and open state, with a devotion to community welfare. Two centuries later, the humanist Leonardo Bruni (c.1377–1444) would praise the Florentine government as follows:

What city, therefore, can be more excellent, more noble? What descended from more glorious antecedents? Which one of the most powerful cities is able to be compared with our own on these grounds? Our form of governing the state aims at achieving liberty and equality for each and every citizen. Because it is equal in all respects, it is called a popular government. We tremble before no lord, nor are we dominated by the power of a few. All enjoy the same liberty, governed only by law and free from fear of individuals. [247]

But then Florence was hit by a plague known as the Black Death. Peaking between 1347 and 1351, the plague swept away between 30% and 50% of Europe’s total population. It left the survivors with a deep sense of despair and disbelief. The chronicler Agnolo di Tura, who had to bury five of his sons, remarked: “So many have died that everyone believes it is the end of the world.” Petrarch wrote:

In the year 1348, one that I deplore, we were deprived not only of our friends but of people throughout all the world. If anyone escaped, [he would the next year be] pursued by a deadly scythe. Will posterity believe [that at this time] nearly the whole world—not just this or that part of the earth—is bereft of inhabitants, without there having occurred a great fire in the heavens or on land, without wars or other visible disasters? When at any time has such a thing been seen or spoken of? Has what happened in these years ever been read about: empty houses, derelict cities, ruined estates, fields strewn with cadavers, a horrible and vast solitude encompassing the whole world? Consult historians, they are silent; ask physicians, they are stupefied; seek the answer from philosophers, they shrug their shoulders […]. Will posterity believe these things, when we who have seen it can scarcely believe it? [We think] it a dream except that we are awake and see these things with our open eyes, and when we know that what we bemoan is absolutely true, […] in a city fully lit by the torches of its funerals, we head for home, finding our longed-for security in its emptiness. O happy people of the next generation, who will not know these miseries and most probably will reckon our testimony as a fable! [248]

Surprisingly, this horror also had an upside. With a severely reduced population, the value of labor soared, which increased the wealth and status of the working class. Especially merchants, bankers, and craftsmen came to dominate the new consumer economy, making the city enormously prosperous.

Petrarch, the founder of humanism

The poet Francesco Petrarca (1304–1374), better known as Petrarch, was born in the Late Middle Ages, but would become the founder of humanism—the life philosophy of the Renaissance. Already at school, Petrarch discovered his love for the Roman classics, especially the works by the great Roman statesman and philosopher Cicero, whom Petrarch elevated as the Renaissance’s ultimate master of eloquence. In the generations that followed, many humanists would deliberately write in Ciceronian Latin. Agostino Dati, in 1471, would even write a manual for sounding like Cicero.

Medieval thinkers had also studied a few texts by Cicero, but these were almost exclusively his works on abstract philosophy, which they read “with no surrender to their charm” (as one modern commentator put it) [249] Instead, medieval thinkers generally read the ancients solely to get a deeper understanding of God and as preparation for the afterlife. This was not the case for Petrarch. He read these works not for any abstract theological end, but for their own sake and without reservation, genuinely hoping to better understand the human condition:

I have read Virgil, Horace, Boethius, and Cicero. I read them not once but a thousand times; […] I brooded over them with every effort of my intelligence. […] I have ingested [them] in such an intimate way that they have become fixed not only in my memory but in my marrow. […] The result is that [they have] taken deep root in the deepest part of my spirit. [246]

To develop a more personal connection with his long-dead Roman heroes, Petrarch would write them mock letters. Instead of using a formulaic style, he wrote them as one friend to another. About his Letter to Cicero, he wrote:

Ignoring the space of time which separates us, I addressed him with a familiarity springing from my sympathy with his genius.

Fig. 411 – Petrarch by Altichiero, from De Viris Illustribus (c. 1375) (Bibliotheque Nationale de France)

Petrarch also set out to rediscover lost Roman texts in libraries across Europe, an endeavor the humanists would later refer to as ad fontes (“back to the sources”). In 1333, while searching in an old Belgian library, he discovered one of Cicero’s orations named Pro Archia, in which he defended the poet Archias in court and praised the “study of the humanities”. In 1345, he made an even more significant discovery, this time in Verona. He found Cicero’s personal letters to his close friend Atticus, to the politician Brutus, and his brother Quintus. These letters gave Petrarch a view into Cicero’s personality and emotions, and also provided him with up-close insight into how Cicero had tried to stop the fall of the Roman Republic. Before the discovery of these letters, Cicero was only known as a stoic larger-than-life figure, but now he was revealed as a real (and flawed) human being, bringing the ancient world to life in an unprecedented way. The discovery was so monumental that it is often identified as the starting point of the Renaissance. On the occasion of finding these letters, Petrarch wrote his first Letter to Cicero:

Francesco to Cicero, greeting. Having found your letters where I least expected them to, after searching long and hard, I read them avidly. I heard you discussing many things, bewailing many things, changing your mind about many things, Marcus Tullius [Cicero], and you whom I had before known as a teacher of others I now, at last, have come to know yourself. [250]

Interestingly, right after this endearing opening, Petrarch jumped on the many mistakes his hero had made in his attempt to save the Roman Republic, including his opportunistic friendly behavior toward Augustus (then Octavian), who would later end the republic:

Now it is your turn to be the listener. Listen, wherever you are, to the words of advice, or rather of sorrow and regret, that fall, not unaccompanied by tears, from the lips of one of your successors, who loves you faithfully and cherishes your name. […] What good could you think would come from your incessant wrangling, from all this wasteful strife and enmity? […] The wise counsel that you gave your brother, and the salutary advice of your great masters, you forgot. [Why] were you so friendly with Augustus? What answer can you give to Brutus? […] You began to speak ill of the very friend whom you had so lauded, although he was not doing any ill to you, but merely refusing to prevent others who were. I grieve, dear friend, at such fickleness. These shortcomings fill me with pity and shame.

In this way, both through the positives and the negatives, he sought true emotional engagement with the great role models of the past.

Other discoveries would soon follow. Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406), who became chancellor of Florence and was reelected every year until his death, found a manuscript containing Cicero’s Familiar Letters, containing letters to his friends. He, too, longed to get to know the real Cicero:

I saw how my Cicero was gentle with his family, how he was disappointed with his son, how he could be hopeless when things were bad, fearful when dangers approached, and how, when times were good, he was serene and satisfied.

Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459) famously recovered a work by the Roman rhetorician Quintilian (c. 35–100) in an old monastery. He wrote the following about the event:

There amid a tremendous quantity of books which it would take too long to describe, we found Quintilian still safe and sound, though filthy with mold and dust. For these books were not in the library, as befitted their worth, but in a sort of foul gloomy dungeon at the bottom of one of the towers, where not even men convicted of a capital offense would be stuck away. [251]

The Dark Ages

Amazed by the beautiful style of Cicero’s Latin, Petrarch noticed how much the Latin language had decayed in the hands of medieval scholars. Compared to Ciceronian Latin, medieval Latin was ugly, uninspiring, and unclear. Studying the works of the Roman historian Livy (60 BC–15 AD), Petrarch came to the same conclusion that something had gone completely wrong during the Middle Ages. As a result of these observations, Petrarch concluded that the ancients were superior to men of his own day, which caused him to develop a deep-seated disappointment with his own era:

Among the many subjects which have interested me, I have dwelt especially upon antiquity, for our own age has always repelled me, so that, had it not been for the love of those dear to me, I should have preferred to have been born in any other period than our own. [249]

In a 2nd letter to Cicero, we read in the same vein:

Now, […] you will wish me to tell you something about the condition of Rome and the Roman republic. […] Trust me, Cicero, if you were to hear of our condition today you would be moved to tears, in whatever circle of heaven above, or Erebus below, you may be dwelling. [249]

He came to associate his own age with darkness (as we do today in the phrase “the Dark Ages”). For instance, he wrote that the few men of genius of his age were “surrounded by darkness and dense gloom.” When asked why he didn’t include the lives of contemporary figures in his work On Illustrious Men, he answered:

[They] offer material suitable not so much for history but rather for satire. I did not wish for the sake of so few famous names […] to guide my pen so far and through such darkness.

In his Letter to Livy, Petrarch also complained that the scholars of his own age had neglected the great works of the past:

We know that you wrote 142 books on Roman matters. You must have worked with such energy and such unremitting zeal. Now, of that entire number barely thirty exist. Later generations, who, not satisfied with their own disgraceful barrenness, permitted […] the writings that their ancestors had produced by toil and application, to perish through insufferable neglect. Although they had nothing of their own to hand down to those who were to come after, they robbed posterity of its ancestral heritage.

The works that did survive the Middle Ages, he complained, were often incomplete and filled with careless errors. In an attempt to restore Livy’s work, Petrarch set out to compare different versions of his work in order to return the text to its original state. This method would become one of the hallmarks of humanism.

While medieval historians usually saw their own era as a continuation of the Roman Empire, be it in a different form, Petrarch began to see a definite break. As a result, he began to divide history into two periods. The first period was the golden age of ancient Greece and Rome, which he described as an age of light, and the second a period of decline following the fall of Rome, characterized by darkness.

But Petrarch wasn’t entirely pessimistic. In some passages, he was hopeful for a brighter future:

Who can doubt that, were Rome to know itself once more, it would rise again?

He just had the bad luck of being born “in the middle” of two great time periods (from which the term “the Middle Ages” is derived):

There was a more fortunate age and probably there will be one again; in the middle, in our time, you see the confluence of misery and disgrace.

On some occasions, he even imagined himself as the initiator of this new period.

About a century later, Leonardo Bruni was confident enough to announce the beginning of a third period, in which the grandeur of Greece and Rome was restored. We now call this period the Renaissance.

Against Scholasticism

In his student years, Petrarch had dropped out of the University of Bologna, believing a rot had crept into the institution. From that point onward, he came to operate from outside the established institutions, as many other humanists would after him. Petrarch claimed that the medieval Scholastic philosophy that dominated the universities throughout Europe had turned education into the study of irrelevant, abstract theological arguments, while doing next to nothing to help people lead good lives. For instance, the great Scholastic philosopher Thomas Aquinas had argued whether “several angels can be in the same place” and whether a cannibal could physically rise from the dead, being composed of other people’s bodies. Petrarch, instead, believed the focus should be on human nature and human flourishing.

Petrarch’s critique of Scholasticism was worked out most extensively in his work On His Own Ignorance and That of Many Others. The book tells of his conversations with four academics in Venice:

[They know] about wild beasts, birds, and fish. [They know] how many hairs a lion has in its mane, how many feathers a hawk has in its tail. [They tell of the] intelligence of the animals and their resemblance to humankind. They tell how the phoenix lives two or three centuries, and is then consumed by an aromatic fire, to be born again from its ashes. In most cases, these things are false, as was revealed when many such animals were brought to our part of the world. Clearly, the facts were not known to those reporting them, and they were more readily believed or more freely invented because the animals were not present. Yet even if they were true, they would contribute absolutely nothing to the happiness of our life. What use is it, I ask, to know the nature of beasts and birds and fish and snakes, and to ignore or neglect our human nature? [246]

Although this needed to be said, it did cause Petrarch to disregard the natural sciences as useless speculations, which might explain the relatively low scientific activity during the Renaissance. What also gave him an anti-scientific bend was that he could read Latin, but not Greek, which gave him access to the more practical-minded Romans, but not to the more abstract-thinking Greeks. Following his lead, the Renaissance became mostly a return to Rome. Salutati did try to right this wrong, when he introduced a Greek teacher from Byzantium to teach in Florence. Leonardo Bruni became one of his students, hoping to set right Italy’s neglect of the Greek heritage:

For seven hundred years now, no one in Italy has been able to read Greek, and yet we admit it is from the Greeks that we get all our systems of knowledge.

Bruni, who became the best-selling writer of the 15th century, made a good start by translating a number of important works from Greek to Latin. All of these works, although written hundreds of years earlier, seemed to speak directly to the problems that the Florentines were struggling with. Take, for instance, Address to the Youth by Saint Basil (330–379). In this text, the Christian theologian explained the importance of studying pagan texts to obtain a correct view of the world. Bruni also translated Plato’s Phaedo, about the death of Socrates. Plato portrayed Socrates as calm and concerned for his loved ones, all the way to the very end. This made Socrates a role model for how to lead a good life. Bruni also tackled Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, which described ethics in a practical way. It made the case that human excellence can be learned and it showed how each individual’s excellence is tied to the flourishing of the community—all ideas the Florentines gladly took to heart.

Now, back to Petrarch. He also began to see the classics as fundamentally human products, which are therefore subject to error and in need of critical analyses. This, too, would become one of the hallmarks of the Renaissance. It was common among late medieval thinkers never to question the classics. Aristotle, in particular, came to be considered an infallible authority. In On His Own Ignorance, Petrarch complained that anytime he criticized Aristotle, his four interlocutors “would look at me as a blasphemer for requiring more than that man’s authority as proof of fact.”

I certainly believe that Aristotle was a great man who knew much, but he was human and could well be ignorant of some things, even of a great many things.

He continued:

These friends of ours, I have already said, are so captivated by their love of the mere name “Aristotle” that they call it a sacrilege to pronounce any opinion that differs from his on any matter. Hence, as the greatest proof of my ignorance, they cite some remark I made about virtue that was insufficiently Aristotelian. Behold a crime worthy of the death penalty! It could easily be that I said something different from and even contrary to their view, but that doesn’t mean that I spoke wrongly, for I was “not bound to swear by the words of any master” as Horace says of himself. [252]

And Petrarch practiced what he preached. As we have seen in his second Letter to Cicero, he was willing to harshly criticize even his own hero. Even when discussing his greatest role model, Petrarch insisted on independent thought. In this vein, he boldly wrote:

“I am my own authority.” [253]

The Secret

In his most famous work, called Secretum (“The Secret”), Petrarch committed his deepest and most private thoughts and feelings to paper. The work was never meant to be published and instead served as a method to sort out his thoughts and feelings, which he claimed had a healing effect on him. This method of self-exploration allowed him to study his inner world to a degree not reached by any other Renaissance figure. He described his special relationship with this work as follows:

So, little Book, I bid you to flee from the places of men and be content to stay with me, true to the title I have given you. For you are my “secret” and thus you are titled. And when I would think upon deep matters, speak to me in secret about what has been in secret spoken to you. [254]

The text is written in the form of a dialogue between Petrarch and Saint Augustine. Petrarch allowed Augustine to expose his flaws, especially his “unchristian” feelings of lust and pride.

His feelings of lust were related to his love for a French woman named Laura, who became his lifelong obsession and the main subject of his poems. These poems were wildly popular, are still regarded as among the greatest works of Italian literature, and even helped shape the modern Italian language. It seems Petrarch mostly loved her from afar, perhaps—as some of his poems indicate—because she was married. Instead, he carried a portrait of her everywhere he went, made by the famous artist Simone Martini (1284–1344). In his personal notes, written on the flyleaf of a book he wrote with his father, we read he was devastated when she died about twenty years after they first met. Unfortunately, we don’t know much more about her. In fact, one of his patrons even doubted whether she truly existed.

In The Secret, we find Petrarch battling between his medieval and his more modern self. Augustine warned Petrarch about the corrupting nature of lust, but then the modern Petrarch breaks through, claiming he could not bring himself to believe that his love for Laura would obstruct his path to salvation. In fact, he believed that it inspired much of his spirituality. Augustine disagreed, showing him that it made him hold Laura in higher esteem than God. Finally, Petrarch gave in to Augustine’s arguments, at least intellectually, agreeing that his inner turmoil and depression had started when he first laid eyes on her.

Petrarch’s feelings of pride were also cause for much tension in his life. On the one hand, he often parroted the medieval notion that life was just a brief preparation for the afterlife, yet, at the same time, he was obsessed like no other with his earthly achievements. He even managed to convince a Roman senator to crown him with a laurel wreath on Capitoline Hill, as had happened to distinguished poets in Roman times.[13] He became the first to receive this honor since the fall of Rome. Petrarch did this hoping to be remembered throughout the ages, as his Roman heroes were. He even wrote a novel, called Africanus, in which he lets Homer foretell his own birth, presenting himself as the pivotal character who would “restore the ancient sisters [the Muses] to Helicon”—that is, restore Rome to its former glory. Although arrogant beyond belief, his attitude did exemplify a renewed trust in the capacity of the individual, which also became a hallmark of the Renaissance. Where medieval artists often preferred to work in anonymity (working not for men, but for the greater glory of God), Petrarch was very conscious of his legacy. He even wrote a Letter to Posterity, a short biography, which (as the title indicates) was written for his future readers. Once more, in his Secretrum, Petrarch eventually agreed with Augustine on an intellectual level, but remained unwilling to lay down his projects.

The Renaissance Man

The humanists in Florence also revived the Roman idea that education should aim at creating competent citizens, willing and able to actively partake in the politics of the city. The need for this development became especially apparent in 1402 when Florence was under siege by Milan and on the brink of losing. They were only saved by an outbreak of the plague just outside the gates of Florence, which killed the leader of the opposing army. To prevent similar threats in the future, it was decided that Florence needed leaders who were better prepared for their civic roles. A good prince, they claimed, should be well-educated and promote education among his citizens. To accomplish this, many Florentines began to study the classics, hoping to find the knowledge and skills necessary to solve the problems of their day. The reach of philosophy, as a result, extended far beyond the academics. Nobles and even merchants now started to study the ancient texts.

The Florentine leader who best exemplified this ideal was Lorenzo de Medici (1449–1492), nicknamed Il Magnifico. His family members had come from plebeian origins but had managed to work themselves up to become one of the richest banking families in Europe. Lorenzo diligently pursued the goal of making Florence the cultural capital of Europe. He spent half the state budget on books and became a patron of the arts, sponsoring artists such as Botticelli and Michelangelo. His influence became so great that he became the de facto ruler of Florence.

Fig. 412 – Lorenzo de Medici (15th or 16th century) (National Galery of Art, United States)

To create competent, virtuous, and well-rounded citizens, the humanists recommended a broad education, which they called the studia humanitatis, from which the name “humanist” was derived. The humanist Battista Guarini (1435–1513), in his work Teaching and Reading the Classical Authors, explained:

Learning and training in virtue are peculiar to man: therefore, our forefathers called them “Humanitas,” the pursuits, the activities, proper to mankind. [255]

According to Vergerio the Elder (c. 1370–1444), the humanities included instruction in grammar, rhetoric, history, moral philosophy, and poetry. He wrote:

We call those studies liberal which are worthy of a free man; those studies by which we attain and practice virtue and wisdom; that education which calls forth, trains and develops those highest gifts of body and of mind which ennoble men, and which are rightly judged to rank next in dignity to virtue only. [255]

Today we call the ideal product of humanist education a Renaissance man. A good example was Baldassare Castiglione (1478–1529), a polymath who was skilled in philosophy, had musical and artistic abilities, and was also versed in the arts of war. Another example is the architect, author, and humanist Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472). A contemporary wrote about him:

His genius is of this sort: to whichever area of study he puts his mind, he easily and quickly excels the others. [122]

The spirit of the Renaissance man is beautifully captured in Alberti’s phrase:

A man can do all things if he but wills them.

Lorenzo Valla and the Donation of Constantine

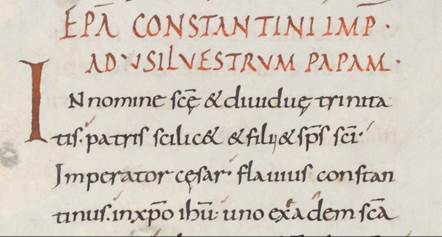

The Roman philologist Lorenzo Valla (1407–1457) took Petrarch’s textual reconstruction to the next level. He began to compare different translations of various historical documents to spot inauthentic passages. His most famous work was the Declamation on the Falsely Believed and Lying Donation of Constantine, which he wrote in his free time when he was secretary at the court of Alfonso of Aragon, who reigned over the kingdom of Naples and Sicily and who was at odds with the pope. In this work he applied his textual analysis to a document called the Donation of Constantine (see Fig. 413). The document was thought to be a decree written in the 4th century by which Emperor Constantine transferred his authority over Rome and the Western Roman Empire to Pope Sylvester (d. 335). The decree, we read, was presented as a gift to the pope for healing Constantine of leprosy through the power of prayer. Understandably, the papacy regularly referred to this document to legitimize its influence over the kingdoms of Europe. Valla studied the Latin language used in the document and discovered that the text was, in reality, a forgery from the 8th century. For instance, he found words in the text that had not yet entered into the Latin language at the time of Constantine (such as the word “feodum,” meaning “fief,” which was a word of Frankish origin). There were also historical inaccuracies. For instance, the text referred to the city Constantinople, which at that time did not yet exist. In his bold writing style, he wrote:

How in the world—this is much more absurd, and impossible in the nature of things—could one speak of Constantinople as one of the patriarchal [jurisdictions], when it was not yet a patriarchate, nor a [jurisdiction], nor a Christian city, nor named Constantinople, nor founded, nor planned! For the “privilege” was granted, so it says, the third day after Constantine became a Christian; when as yet Byzantium, not Constantinople, occupied that site. [256]

Fig. 413 – A 9th-century version of the Donation of Constantine, in a manuscript now known as the False Decretals, as it contains a great number of forged documents. The text in red reads: “Letter from Emperor Constantine to Pope Sylvester.” (St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 670, page 318)

Valla also found it suspicious that no other 4th-century authors had mentioned the decree, which was strange for such an important gift (“This Donation of Constantine, so splendid and unexampled, can be proven by no document at all.”). He thus concluded, again in his arrogant style:

Therefore, this text is not by Constantine but by some foolish petty cleric who does not know what to say or how to say it. Fat and full, he belches out ideas and words enveloped in fumes of intoxicating wine. [257]

The Donation wasn’t the only text that Valla unmasked. In 1444, he was put on trial before the Catholic Inquisition for claiming that a text called the Apostle’s Creed could not have been written by the apostles. His patron Alfonso of Aragon personally intervened to protect him from imprisonment.

But eventually things turned in Valla’s favor when the humanist pope Nicholas V (1397–1455) was installed. Luckily for Valla, Nicholas appreciated his work and was also an ally of the house of Aragon. He even made him papal secretary, the highest rung of the papal court, where he was deployed for Greek-to-Latin translations.

Correcting Holy Scripture

Even more controversially, Lorenzo Valla also applied his new linguistic skills to Holy Scripture itself in his Annotations to the New Testament (1449). He studied Saint Jerome’s Vulgate Bible, the standard Latin translation of the Bible from the 4th century, and discovered many translation errors. This should not have been surprising, since Jerome himself had admitted that he (as any human would) had probably made some mistakes translating such an immense work. Yet not long after, his translation came to be seen as the infallible word of God. As a result, the Church no longer found it necessary to consult the original Greek text, even in the most important matters.

Valla opened the preface to his work with the following lines:

That pope, whom Jerome deservedly calls most blessed and who was most skilled in all branches of learning, nevertheless indicated that he was not sufficiently skilled in the Greek language, when he instructed Jerome himself to find which Latin exemplars of the New Testament corresponded to the Greek truth. [177]

Valla explained that he felt called to “find those places in the New Testament where, like certain places in a temple, it is ‘leaking,’ so to speak.” Since in Jerome’s time there were already many versions of the Bible, “it is almost definite that after a thousand years […] this stream, which was never cleansed, has taken on some filth and pollution.”

Lorenzo made clear that his criticism of the Vulgate was not a critique of the word of God, but just a critique of the translation. His Italian critics, however, did not give him the benefit of the doubt. One of his critics, Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459), wrote:

This profane man hates Holy Scripture so much that he claims much in it is not written correctly. […] The arrogant Valla dares to open his mouth even against Jerome. [258]

Ironically, Poggio made these claims unable to read Greek himself. Valla responded as follows:

If I am correcting anything, I am not correcting Sacred Scripture, but rather its translation, and in doing so I am not being insolent toward scripture but rather pious, and I am doing nothing more than translating better than the earlier translator, so that it is my translation—should it be correct—that ought to be called Sacred Scripture, not his. [177]

If Jerome would come back to life, Valla claimed, “he would correct what has been corrupted and ruined in certain copies, in just the same way as I am doing in my [Annotations], a work that you, Poggio, claim is motivated by hatred.”

Valla only spread his Annotations among a small circle of acquaintances. One copy ended up in a monastery library in Leuven, Belgium, where the great Dutch humanist Erasmus (1466–1536) found it and then spread it widely through the printing press. There, in Western Europe, the work became one of the dominoes that eventually led to the Reformation (see the next chapter).

The oration on the dignity of men

Humanism also created a more positive outlook for humanity. In medieval days, it was common to believe that mankind had fallen. For instance, Pope Innocent III (c. 1160–1216), in his work On Contempt for the World, encouraged his readers to contemplate the irredeemable state of humanity in order to convince them to focus on the hereafter. The humanist, in contrast, agreed with the Greeks and the Romans that living a good life was in itself a noble pursuit. Mankind was not inherently broken but was instead praiseworthy. Similarly, the human body was not corrupt but a masterpiece.

The medieval population also often felt they were little more than subjects—of God, the Church, and their king. They generally accepted their place in the social hierarchy, believing God had preordained them for their roles. God had made a ruler a ruler, a priest a priest, and a peasant a peasant. This idea was known as the Great Chain of Being, which postulated the existence of a God-given hierarchy among all of creation, starting with inanimate matter and moving through animals, humans, and angels all the way up to God. Within humanity, further distinctions were made between the pope, archbishops, bishops, priests, but also kings, dukes, knights, peasants, and so on. The system served a powerful function for the elites of society. As the hierarchy was believed to be installed by God, it became a sin to attempt to rise in the ranks or rebel against a king. Everyone was to perform the role they were born into, following God’s preordained plan. For kings specifically, this idea became known as the Divine Right of Kings.

In contrast, humanists believed humans have the ability to choose their own destiny. This ideal is perhaps best expressed in a work that became the quintessential humanist manifesto: The Oration on the Dignity of Men by Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494). Giovanni placed humanity on a pedestal, claiming “there is nothing to be seen more wonderful than man.” [122] He claimed God had created man after creating the universe because he “longed for there to be someone to ponder the meaning of such a magnificent achievement, to love its beauty and to marvel at its vastness.” He then presented what would become the archetypical Renaissance vision of man:

Adam, we give you no fixed place to live, no form that is peculiar to you, nor any function that is yours alone. According to your desires and judgment you will have and possess whatever place to live and whatever form and functions you yourself choose. All other things have a limited and fixed nature prescribed and bounded by our laws. You with no limit or bound may choose for yourself the limits and bounds of your nature. We have placed you at the world’s center, so that you may survey everything else in the world so that with free choice and dignity you may fashion yourself into whatever you choose. To you is granted the power of degrading yourself into the lower forms of life, the beasts. And to you is granted the power contained in your intellect and judgment to be reborn into the higher forms, the divine. [252]

What a radical affirmation of human capacity! How far have we come since the days of willing human sacrifice? About this transition, the famous mythologist Joseph Campbell wrote:

One final distinguishing feature [of the Renaissance, was its vision] of a mankind of individuals, self-moved to ends proper to themselves, directed not by the constraint and noise of others, but each by his own inner voice. [...] Such an idea could never have been made in, for instance, Sumer. It would have been simply meaningless. Authority there was from the order of the heavens, for which people would walk with the king into his grave, which points to an incredible impersonality of lives in dedication to a mythical story. [222]

Machiavelli’s Prince

Niccolo Machiavelli (1469–1527) took the practical focus of humanism to its extreme in his work called The Prince, which became one of the most influential and controversial books on political philosophy. In this work, Machiavelli claimed that princes should cast away notions of right and wrong and do whatever it takes to further their political causes. In fact, a prince in the real world of politics often has no choice but to “enter into evil,” [259] as it often is the only way to preserve political power.

While earlier philosophers, such as Plato and Cicero, had wasted their time using abstract standards such as justice and reason to conjure up “imagined republics that have never been seen or known to exist in truth,” Machiavelli set out to discover what the great leaders of the past had actually done. He was finally willing to say in public what the great leaders of the past had known all along—what they had “whispered in restricted gatherings or couched in private letters and memoranda.” [259]

Even more controversially, Machiavelli also claimed Christianity made ineffective rulers, as the inclination to always do good prevented them from doing what was necessary. He wrote:

In order to preserve a state, especially in war, one must set aside the principles of Christian morality.

In a remarkably modern analysis, he continued:

Our religion has glorified humble and contemplative men more than active men. It has then placed the highest good in humility, abjectness, and contempt of things human; [the pagans] placed it in greatness of spirit, strength of body, and all other things capable of making men very strong. And if our religion asks that you have strength in yourself, it wishes you to be capable more of suffering than of doing something strong. This mode of life thus seems to have rendered the world weak and given it in prey to criminal men. [259]

Ironically, Machiavelli saw the popes of his day as great examples of his ideal prince. Pope Alexander VI (1431–1503) had shown Machiavelli “how far a pope could prevail with money and forces,” claiming he “never did anything, nor ever thought of anything, but how to deceive men,” while to the public he claimed to be “all mercy, all honesty, all humanity, all religion.” Alexander VI, among other things, misused his power to enrich his many illegitimate children and gave them high positions in the Church, increasing the influence of his family line. As a diplomat of the Florentine republic, Machiavelli also got close to Pope Julius II (1443–1513), giving him “the chance to follow a pope who rode at the head of an army”. He claimed his experience to have been a “unique opportunity to study the actions of an unusual prince, who brandished a sword in one hand and the scepter of Saint Peter in the other.” [259]

Giotto and the start of Renaissance art

The new developments during the Renaissance are also beautifully reflected in art. In the Middle Ages, artists often worked anonymously for the Church, seeing themselves more as craftsmen. The Church also had precise ideas about both the content and style of the works they commissioned, allowing little room for artists to distinguish themselves. Also, since the purpose of medieval art was generally to instruct viewers on matters of religion, they were mostly asked to create stylized and stereotypical representations that would immediately remind the people of particular religious stories.

The first Renaissance artist was Giotto (1266–1336), who technically still lived in the Middle Ages. Unlike the flat characters in medieval art (see Fig. 414), Giotto’s characters seemed to take up three-dimensional space (see Fig. 416 and Fig. 415). He also managed to display human emotion like never before by drawing realistic gestures and facial expressions, making his characters much easier to identify with. Giotto’s art pulled people into the scene, awakening in them an emotional experience, which became one of the defining traits of Renaissance art. This development paralleled a trend in the population to seek a more emotional and personal involvement with religion (as we will learn in the next chapter).

Fig. 414 – A typical medieval drawing with stylized figures (Bibliotheque Nationale de France)

Fig. 415 – Lamentation of Jesus by Giotto (c. 1305 AD) (Scrovegni Chapel, Italy)

Fig. 416 – Death of Saint Francis by Giotto (1325 AD) (Basilica of Santa Croce, Italy)

Celebrating Giotto’s achievement, the humanist Matteo Palmieri (1406–1475) beautifully described the excitement that was in the air during the Renaissance:

Where was the painter’s art until Giotto restored it? A caricature of the art of human delineation! Sculpture and architecture, for long years sunk to the mere travesty of art, are only today in the process of the rescue from obscurity; only now are they being brought to a new pitch of perfection by men of genius and erudition. Of letters and liberal studies it would be better to be silent altogether. For these, the real guides to distinction in all the arts, the solid foundation of all civilization, have been lost to mankind for 800 years and more. It is but in our own day that men dare to boast that they see the dawn of better things. For example, we owe it to our Leonardo Bruni that Latin, so long a byword for its uncouthness, has begun to shine forth in its ancient purity, its beauty, its majestic rhythm. Now indeed may every thoughtful spirit thank God that it has been permitted to him to be born in this new age so full of hope and promise, which already rejoices in a greater array of nobly gifted souls than the world has seen in the thousand years that have preceded it. [260]

Fig. 417 – Portraits of Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza by Piero della Francesca (c. 1475) (Uffizi Museum, Italy)

In time, merchants and bankers also became rich enough to buy their own art. Although they too had specific demands for their work, they did generally give artists more freedom, which greatly contributed to artistic individualism. The rich Florentines also stimulated the return of portraiture (see Fig. 417). As the new elites wanted to be memorialized by the great artists of their day, they were willing to pay enormous sums of money. In the process, these artists became incredibly famous and influential. The greatest Renaissance artists were rightfully considered geniuses, and the public became interested in their lives. The artist and historian Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) popularized them with his work The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. His descriptions made the artists of his time seem larger than life, turning them into legends. Vasari helped to make the lives of artists just as worthy of examination as the lives of kings and popes.

Perspective

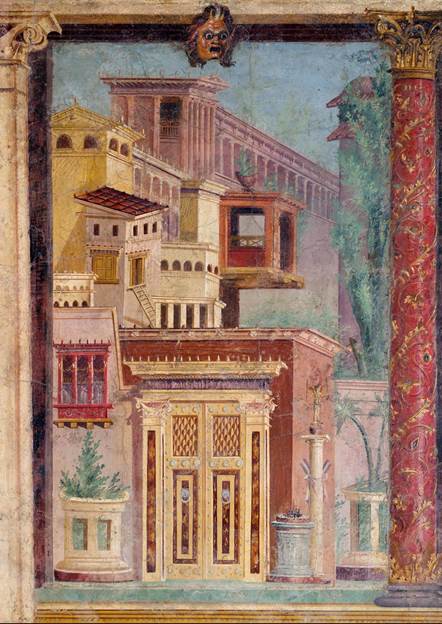

Renaissance artists also discovered how to properly draw perspective. In Fig. 418, we see a failed attempt from the Middle Ages. Notice how the characters are awkwardly related to the surrounding architecture and how the cups on the table seem to defy gravity. The Greeks and Romans came closer to the correct depiction of depth. Aristotle had described painted panels used on the theater stage to give the illusion of depth, and some paintings found in the ruins of the Roman town Pompeii show remarkable realism and an almost correct application of perspective (see Fig. 418).

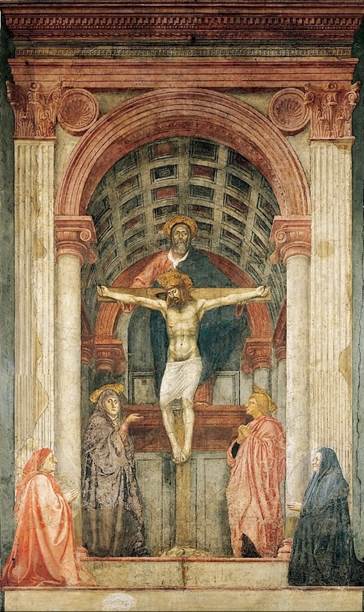

The geometrically correct method of drawing perspective was discovered in the Renaissance by the architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446). He famously demonstrated how perspective worked by painting the outlines of various Florentine buildings onto a mirror, pointing out that parallel lines on a horizontal plane converged on the horizon. According to Vasari, he also placed a painting of the Baptistery of Florence next to the actual building. He then had viewers look through a small hole from the back of the painting at the actual building. He would then place a mirror in front of them, reflecting the painting back at them. To the viewer, the painting and the real building were nearly indistinguishable. The same Brunelleschi, it has to be mentioned, also designed the famous dome of Florence, one of the most beautiful buildings in world history (see Fig. 420). The Renaissance artist best known for his use of perspective is Masaccio (1401–1428). His work is shown in Fig. 422 and Fig. 423.

Fig. 418 – A failed attempt at perspective by a medieval artist. The table is drawn without a sense of depth, making the objects on it seem to float.

Fig. 419 – Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, just north of Pompeii (c. 50 BC) (The MET, United States)

Fig. 420 – Brunelleschi’s gigantic dome of Florence’s cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (© Adobe Stock)

Fig. 421 – Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, just north of Pompeii (c. 50 BC) (The MET, United States)

Fig. 422 – Raising of the son of Theophilus of Antioch by Masaccio (c. 1425 AD) (Cappella Brancacci, Italy)

Fig. 423 – The Holy Trinity by Masaccio (1425 AD) (Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, Italy)

Michelangelo

The best Renaissance sculptor was Michelangelo (1475–1564), who was also a genius painter and architect. His most famous sculpture is the David (see Fig. 424). The anatomical beauty of this work was unprecedented in world history. With this work, Michelangelo displayed the human body as almost divine. David’s body has ideal mathematical proportions and his tense look reveals a deep psychology. In line with the main message of humanism, Michelangelo made the human figure not an insignificant speck compared to the might of God, but instead presented it as the masterpiece of creation. With Michelangelo, the human body and also the human individual came to be seen as worthy and capable of doing great deeds. With this one work, he summed up the most important lesson of the Renaissance and changed the world.

Michelangelo’s greatest masterpiece in painting can be found on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. The most famous part of this massive painting is the Creation of Adam (see Fig. 425), which has a message similar to his David. Here, we see Adam depicted as a powerful figure, who comes close to touching God who is about to grant him life.

Fig. 424 – David by Michelangelo (c. 1500 AD) (George Groutas, CC BY 2.0; Galleria dell’Accademia, Italy)

Fig. 425 – The creation of Adam by Michelangelo (c. 1508 AD) (Sistine

Chapel, Italy)

The greatest masterpiece of Rafael (1483–1520) can also be found in the Vatican. It is called the School of Athens and celebrates ancient intellectuals (see Fig. 427). In the middle, we see Plato pointing upwards to the heavenly forms, while Aristotle points to the earth as the source of knowledge.

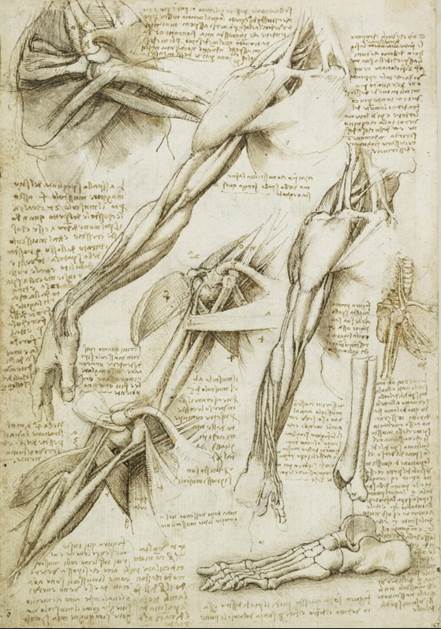

Leonardo da Vinci

The polymath Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was another true Renaissance man. Da Vinci had an almost superhuman talent for just about everything. He was a pioneering sculptor, painter, inventor, engineer, anatomist, and more. Only fifteen of his paintings have survived, and all are among the greatest masterpieces of all time. As an inventor, Leonardo made sketches of airplanes, helicopters, tanks, submarines, and much more, but sadly, he never turned these ideas into reality. He also dissected corpses in a hospital in Florence, which gave him an unprecedented understanding of anatomy (see Fig. 426). His drawings and notes on the subject would undoubtedly have made a great contribution to medical science had he published them.

In 1543, Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) did publish a massive work on the human body, called The Structure of the Human Body, with 273 plates showing human anatomy in remarkable detail through progressive stripping of skin, tissue, muscle, organs, all the way down to the bones.

Fig. 426 – One of Da Vinci’s groundbreaking

anatomical drawings.

Leonardo wrote his personal notes in mirror. The purpose of this practice

remains unknown. It could be to avoid smearing out the ink as a left-handed man

(Royal Collection Trust, Britain)