Starting in the 16th century, various thinkers began to downplay philosophical speculation on the universe in favor of data-driven—also called, empirical—theories. Most crucial at this stage was the development of the scientific method by Francis Bacon, which gave scientists a way to reliably separate credible knowledge from superstition, which led to a period known as the Scientific Revolution.

Various thinkers also studied the limitations of human knowledge. John Locke rightly pointed out that without sensory data to validate a claim, we are unable to verify whether this claim is right or wrong. Instead of making things up or claiming some special knowledge beyond the senses, we should admit our ignorance in these cases.

Rene Descartes made the ultimate attempt to bypass the uncertainty of science by applying his method of doubt, which entailed discarding any knowledge that could be doubted in any way. The only thing left over was his ability to doubt itself, which allowed him, so he claimed, to prove his own existence (“I think, therefore I am”).

The scientific method

One of the greatest achievements of the Scientific Revolution was the formulation of the scientific method by the British philosopher Francis Bacon (1561–1626). Bacon did not discover anything new about the world but instead created a method to obtain reliable knowledge. He wrote his ideas down in a work called the Novum Organum (“New Organon”), which was an attempt to improve on Aristotle’s Organon, in which he too discussed how to attain credible knowledge about the world.

He began by noticing that many of our ideas about the world are distorted by our biases, which he called the idols of the mind. As his first example, he mentioned the idols of the tribe, which are those biases that “have their foundation in human nature itself.” [275] As an example, he mentioned the predilection of the human imagination to detect patterns that aren’t there. The idols of the cave are prejudices peculiar to the individual. “Everyone,” he claimed, “[...] has a cave or den of his own, which refracts and discolors the light of nature,” since everyone is colored by “his education and conversation with others […] and the authority of those whom he esteems and admires.” He next described the idols of the market, which are caused by inaccuracies in language, as words can be imprecise or spring from false theories. The final biases he called the idols of the theater, by which he referred to the tendency of philosophers to create grand yet false theories about the world based on semi-logical arguments. He wrote:

Lastly, there are Idols which have immigrated into men’s minds from the various dogmas of philosophies, and also from wrong laws of demonstration. These I call Idols of the Theater, because in my judgment all the received systems [of philosophy] are but so many stage plays, representing worlds of their own creation after an unreal and scenic fashion. [275]

Bacon claimed that the Greeks had put too much emphasis on logical thinking without demanding evidence to support their claims. The Greeks were often so impressed by the internal consistency, elegance, and simplicity of their logic that they saw no need to support their ideas with rigorous measurement. The Greeks had often already “made up their minds before trying anything out” [276] and as a result, their “philosophizing” often led to beliefs in all kinds of unfounded “fantasies.”

Instead, Bacon recommended the systematic study of nature—or what we would today call empiricism. To obtain credible information, scientists first have to perform repeated measurements which they collect impersonally, that is, without interpretation, to avoid injecting our own prejudices into the theory. According to Bacon, it should not be our interpretation but “the experiment itself that shall judge the [phenomenon].” [276] Only when we have collected enough data do we search for patterns. In case we find one, it is important to repeat the experiment a couple of times to see if the pattern persists. If it does, we have produced new knowledge. At this point, Bacon claimed, we might get tempted to immediately use this new knowledge to come up with a new comprehensive system of the world or give metaphysical explanations for what we have discovered, but Bacon warned that this would almost inevitably introduce fantasy into our theory. Let’s take an obvious example from ancient Greece. The philosopher Thales had correctly observed that water can exist as a solid, a liquid, and a gas and that water is essential for life. From this, however, he immediately went astray by concluding that everything in the universe must, in its essence, be made of water. Bacon recommended avoiding these all-encompassing theories and instead stick as closely as possible to the empirical evidence.

Fig. 461 – Francis Bacon (1617) (Lazienki Palace, Poland)

Bacon recognized two ways of collecting data. The first method is to observe events that naturally occur in the world. This was the method endorsed by Aristotle, but, according to Bacon, it generally only touched nature “by the fingertips.” [276] There are cases where this method is appropriate, for instance when studying the stars, but the universe is often too complex for us to distinguish the phenomenon under investigation from whatever happens simultaneously. For example, when we study gravity, it is not sufficient to simply study falling objects, since their motion is distorted by air friction. To avoid this problem, Bacon recommended experimentation, which requires scientists to artificially design a controlled environment in which we can isolate the phenomenon under investigation while keeping all other variables constant. Only through these probing tests, Bacon believed, can we truly get to the bottom of things. Or in his own words: “the nature of things betrays itself more readily under the vexations of art [meaning through experiment] than in its natural freedom.” [276] To study Nature, he claimed, we need to “bring force to bear on matter” as Nature reveals its secrets faster “if matter be laid hold on and secured by the hands.” He compared this process to the immortal Proteus, from Greek mythology, who only revealed his secrets when handcuffed and bound up with chains. Leibniz would later say that Bacon advocated “putting nature on a rack” to torture her for her secrets. [276]

An example of an experiment is to study gravity by forcefully removing the air out of an enclosed space, creating a vacuum, allowing objects to fall without the effects of air friction. To this day, physics teachers show their students that a feather and a stone fall at the same rate in a vacuum, disproving Aristotle’s theory that heavy objects fall faster than light objects under the influence of gravity.

Bacon also realized that science is more than just a way to satisfy our curiosity about the world, but could also be used to improve our quality of life. He claimed the “goal of the sciences is none other than this: that human life be endowed with new discoveries and powers” in order to “establish and extend the power and dominion of the human race itself over the universe.” As examples, he named three major inventions of China:

[We can see this] nowhere more conspicuously than in those three [discoveries] which were unknown to the ancients, […] namely, printing, gunpowder, and the compass. For these three have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world […] such that no empire, no sect, no heavenly force seems to have exerted greater power and stimulus in human affairs. [40]

The belief that science can improve life would become one of the hallmarks of the Enlightenment.

From alchemy to chemistry

The impact of the scientific method was especially clear in chemistry. The ancient study of alchemy was still going strong in the 17th century, where it had supporters among the foremost scientists of the Scientific Revolution. Even Isaac Newton (1642–1726) had tried to solve the mystery of the philosophers’ stone. In fact, the majority of his notebooks are not about gravity, but about alchemy.

Others had come to detest alchemy for its secrecy and incomprehensible mysticism, not to mention the charlatans who produced counterfeit gold. The general public also had a negative opinion, viewing alchemists as filthy, delusional, and fraudulent. For instance, Vasari wrote the following about the famous artist-turned-alchemist Parmigianino (1503–1540):

But it soon appeared that he was neglecting the work in the Steccata [a church], or at least taking it very easily; it was evident things were going badly with him; and the reason was that he had begun to study alchemy, and to put aside painting for it, hoping to enrich himself quickly by congealing mercury. He used his brains no longer for working out fine conceptions with his pencils and colors, but wasted all his days instead over his charcoal and wood and glass bottles and such trash, spending more in a day than he earned in a week by his painting in the Steccata. Having no other means, he began to find that his furnaces were ruining him little by little, and what was worse still, the company of the Steccata, seeing that he neglected his work, and having perhaps paid him beforehand, began a suit against him. He therefore fled by night

But his mind was constantly turning to his alchemy, and he himself was changed from the gentle, delicate youth to a savage with long, ill-kept hair and beard, and in this melancholy state, he was attacked by a fever, which carried him off in a few days. [277]

The first modern chemist, Robert Boyle (1627–1691), even felt the need to apologize in the preface of his first book on chemistry for devoting himself to “such vain, useless, if not deceitful a study.” [278] He was determined to save chemistry from the lunacy of the past by developing an “experimental philosophy” which was highly influenced by Francis Bacon. He criticized his predecessors for reaching conclusions based on insufficient evidence, flawed measurements, and unchecked assumptions. He also resisted the alchemical practice of presenting theories as the undeniable, God-given truth. Instead, he insisted that every theory should be regarded as a hypothesis that could, in principle, be overthrown if contradicting evidence was found. Boyle also set out to end the vague and inconsistent language of alchemy. Information should not be hidden behind a secret code language, but should instead be written down clearly and precisely. Data should also be made public so that other scientists can reproduce the results and make improvements. We read:

Experiments [should be] so delivered as that an ordinary reader, if he be but acquainted with the usual chemical terms, may easily enough understand them. […] This way, the readers did not have to take anything on faith.

In his work The Skeptical Chemist, he described the need to “[draw] the Chemists Doctrine out of their dark and smoky laboratories, and [bring] it into the open light and [show] the weakness of their proofs.” This would allow “judicious men calmly and after due information to disbelieve it” and would oblige “abler Chemists [...] to speak plainer than hitherto has been done, and [to bring forth] better experiments and arguments.” [279]

Despite these modern ideas, however, Boyle did still believe in the philosophers’ stone. In an unpublished work, he even gave a first-person account of a demonstration of the transmutation of substances into gold and was even allowed to test the gold to verify its authenticity. He even testified before Parliament to the reality of transmutation. Boyle also claimed that the stone could function as a “universal medicine” and could be used to attract and communicate with angels, which, he believed, could be used to push back against the growing tide of atheism. He also cited some cyclical chemical processes as evidence for the resurrection of Christ and concluded that chemistry was a Christian activity. [223]

Clearly, both Boyle and Newton, despite their brilliance, had not yet fully shaken off the magical thinking of the past. However, change was in the air. In 1699, the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris accepted a number of chemists, giving chemistry an official place in academia for the first time. In the decades that followed, alchemy and chemistry came to take on different meanings, which increased the status of chemistry. Alchemy was now seen as fraudulent and belonging in the same category as witchcraft, astrology, and prophecy. It had become unworthy of the Age of Reason. In contrast, chemistry became a modern, respected science, based on reason and evidence. Yet, in secret, some scientists continued their search for the stone.

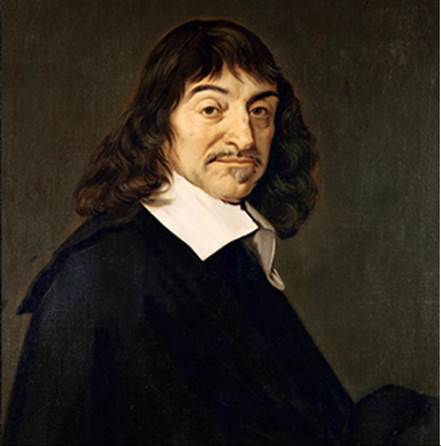

Rene Descartes

The great French philosopher Rene Descartes (1596–1650) took the new skepticism of the scientific age to the extreme in his book Discourse on Method (1617). Like Euclid had done for geometry, Descartes wanted to derive the entire world from a set of self-evident principles. To find these principles, he used his method of radical doubt, which entailed weeding out all knowledge that could be doubted in any way (for which he was driven out of France as a heretic). With this method, he attempted to rid humanity of all error until only a firm foundation remained on which the rest of his theory could be built:

I reject as absolutely false everything in which I could imagine the least doubt, so as to see whether, after this process, anything in my set of beliefs remains that is entirely indubitable. [280]

He concluded that even the external world could be doubted since it could, in principle, be nothing more than a figment of our imagination. In theory, said Descartes, we cannot be completely sure a demon is not deceiving us to make us think we have sensory experiences. There is, however, one thing that cannot be doubted in any way—our ability to doubt. Even if we doubt everything, we are still doubting. And since “doubting” is a mode of thinking, this also confirms the existence of our mind. In his own words:

We cannot doubt of our existence while we doubt. [281]

Or, more famously:

While we thus reject all of which we can entertain the smallest doubt— and even imagine that it is false—we [can] easily suppose that there is neither God, nor sky, nor bodies, and that we ourselves even have neither hands nor feet, nor, finally, a body; but we cannot in the same way suppose that we [do not exist] while we doubt of the truth of these things; for there is a repugnance in conceiving that what thinks does not exist at the very time when it thinks. Accordingly, the knowledge, “I think, therefore I am,” is the first and most certain that occurs to one who philosophizes orderly. [281]

This, he believed, was the only secure logical foundation for knowledge in the face of radical doubt. It became the axiom of his system of the world.

But no matter how brilliant and radical his idea was, his theory quickly ran astray. His next step was to find proof for the existence of God. He reasoned that since man is imperfect, he cannot conceive of the concept of God since God is a perfect concept. God, therefore, could not have been made up by us and therefore has to exist. He then continued to argue that since God is perfect, he must also necessarily be good and would, therefore, not permit us to make mistakes in our theories of the universe without giving us a way to correct these mistakes. This, according to Descartes, proved that the world was, in principle, totally comprehensible by the human mind. Clearly, we have ended up with exactly the pseudo-logical mind games that Bacon warned us about. Nevertheless, his willingness to doubt everything, including received traditions and commonly held beliefs, made a great impression on the West.

Interestingly, Descartes did not apply his method of doubt to the Bible. In his Discourse, he simply stated he “put aside […] the truths of the faith,” avoiding the topic altogether. It is plausible he did this to avoid controversy, since many of the claims in the Bible certainly would not survive his method of radical doubt. Other philosophers, most notably Spinoza, would soon push his method to its logical conclusion, doing away with all supernatural claims in the Bible.

Fig. 462 – Rene Descartes (17th century) (Louvre, France)

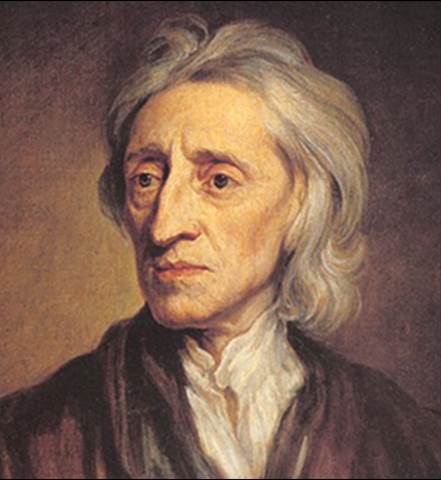

John Locke

The great British philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) expanded on Bacon’s ideas. In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, he set out “to inquire into the […] certainty and extent of human knowledge.” Following Aristotle, he claimed that we are born with an empty mind and that all our knowledge of the world comes from the units of experience we receive through the senses:

Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper, void of all characters, without any ideas: how comes it to be furnished? […] To this I answer, in one word, from experience. In that all our knowledge is founded. [282]

This means that our knowledge is strictly limited to whatever can be confirmed through the senses. Yet much of the world is beyond our experience. Any philosophizing about this is by definition mere speculation, since without any sensory data, we are unable to verify whether these theories are right or wrong. Instead of making things up or claiming some special knowledge beyond the senses, we should instead admit our ignorance.

As his main example, he tackled various theories on the nature of the mind. For instance, he discussed Descartes’s theory that the mind exists separate from the body. How can we possibly know for sure whether God has given our material body the faculty of thinking or whether he added a spirit to the material body? Without any evidence to test these claims against objective reality, there is no way for us to find out which theory (if any) is correct. He concluded that theorizing about the nature of the mind is meaningless and philosophers who engage in this are not scientists, but merely “novelists of the mind.” Instead, we should proceed as follows:

In the present question, about the immateriality of the soul, if our faculties cannot arrive at demonstrative certainty, we must content ourselves in the ignorance of what kind of being it is. [282]

Fig. 463 – John Locke by Godfrey Kneller (1697) (Hermitage Museum, Russia)

Locke even argued that we cannot even meaningfully theorize about the nature of matter, calling it in essence “as obscure and inconceivable” as the mind. This idea was worked out further by George Berkeley (1685–1753), who discarded the concept “matter” as a meaningful notion. We, as human beings, are unable to know what matter is in some ultimate sense beyond experience. Instead of fruitless metaphysical speculations about the inner nature of things, he recommended studying how matter behaves. This is within the grasp of our senses and, therefore, can actually give us insight into how the world works.

Locke also realized that knowledge from the senses is never fully reliable and, therefore, no scientific statement can be exempt from the possibility of being disproven. Locke, therefore, recommended that one not become attached to any scientific viewpoint too strongly:

Whatever I write, as soon as I discover it not to be truth, my hand shall be the forwardest to throw it into the fire. [283]

From what we have discussed so far, you might have concluded that Locke would have doubts about the existence of God as well (as this concept is equally beyond the senses), yet this was not the case. To most pre-Darwinian minds, the very fact that intelligent life exists, is direct evidence of God. Locke also regarded the miracles documented in the Bible as proof of God’s existence and he also strongly opposed atheism (despite his usual outspoken religious tolerance), fearing the denial of God could undermine social order and lead to anarchy.

David Hume and Immanuel Kant

A century later, David Hume (1711–1776) showed that the uncertainty in science ran deeper than was previously thought. For instance, science is subject to the problem of induction. Induction is the process of making universal statements about the world based on a finite number of measurements. Hume pointed out that this method was inherently uncertain as our knowledge of a limited number of instances could never conclusively prove a statement about an infinite number of cases. For instance, scientists believe that all pieces of copper conduct electricity, yet we can never test every piece of copper in the universe. Therefore, even a simple statement such as “all copper conducts electricity” is based on a metaphysical belief in a regularity in nature—just the type of beliefs that Francis Bacon sought to avoid. In the case of the conductivity of copper, the evidence is so overwhelming that it is likely true, but in many other cases, induction can cause trouble. For instance, philosophers of the past used the statement “all swans are white” as a textbook example of induction. All swans, thus far, had been white, so it seemed reasonable to assume that they were all white. But then a black swan was discovered in Australia.

Hume discovered a similar problem concerning causation. He noted that scientists often relied on cause and effect to answer scientific questions, yet causation cannot be directly observed. When one billiard ball hits another, it is assumed that it was the first ball that caused the second ball to move, yet we cannot see that one event is causing the other. Causation is, therefore, also a metaphysical belief. In the case of billiard balls, assuming causation is probably safe. In other cases, however, it can lead us astray. For instance, since the rise of the star Sirius always coincides with the flooding of the Nile, the Egyptians came to believe that Sirius causes the flooding. In reality, however, it later turned out that the rotation of the earth around the sun causes both the rise of Sirius and the seasons, which, in turn, causes the flooding of the Nile. The correlation between Sirius and the Nile, therefore, does not imply causation.

Finally, Hume came to realize that while scientists can demonstrate the validity of “is-statements,” such as “the earth is spherical,” they cannot in the same way tackle “ought-statements,” such as “people ought to be respectful to each other.” With empirical science alone, it is impossible to go from an “is” to an “ought,” forming an impediment to the creation of a fundamental scientific theory of ethics.

Despite these powerful critiques of science, Hume was a strong supporter of the scientific method. Despite its shortcomings, he regarded it as our only path to knowledge. He wrote:

If we take in our hand any [book] of divinity or school of metaphysics, [...] let us ask: Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion. [284]

The philosopher Immanuel Kant

(1724–1804), in his Critique [meaning “analysis”] of Pure Reason,

tried to counter Hume’s criticisms of the scientific method, which he

regarded as a threat to the attainment of certain knowledge. Kant

recognized that through the senses we can only see “the appearance” of an

object, but not the object itself (the “Ding an Sich”). Kant

called knowledge attained through the senses “a posteriori” knowledge,

as it can only be gained “after” using the senses. Instead, he

looked for a way to attain “a priori” knowledge, which can even

be attained “before” any measurement by the senses is done. But what knowledge

can we gain without even looking at the world? For this, Kant pointed to the

ability of our brains to process space and time. We are not sure that

space and time exist in the world, but we do know it exists in the brain as a way

to organize reality for us. From the concept of space, we can derive Euclidean

geometry, which is logically the only possible way to describe space.

Similarly, he tried (but failed) to show that Newtonian physics is the only

possible physics given our notions of time and space, so that it too can be

known a priori. Although he never got much further, his

way of thinking would remain influential in both philosophy and physics.