Processing the monumental discoveries of the Scientific Revolution, the philosophers of the 17th and 18th centuries came to hold unparalleled confidence in the power of human reason to shape a better world. These beliefs gave rise to the Age of Enlightenment.

The collapse of Christian cosmology forced Enlightenment thinkers to revisit their belief in God. Many intellectuals adopted the Deist position, meaning they believed in the existence of God but rejected the idea that God is concerned with the lives of individuals or that he intervenes in the world through miracles or revelation. Their God, instead, was an impersonal force that had created the laws of nature at the beginning of time and then let the universe run its own course. The only way to get to know this God was to study its creation, turning science into a divine discipline.

The Enlightenment

The Scientific Revolution, which focused on understanding the physical world through experiments and calculations, seamlessly transitioned into the Enlightenment, during which the success of science was used to reinterpret religion and the humanities. Enlightenment philosophers, inspired by the success of science, developed an unparalleled optimism in the power of Reason to shape a better world—promising the advent of an Age of Reason. They bravely ventured into this new world, following Truth wherever it might lead them. The philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) famously answered the question “What is Enlightenment?”:

Enlightenment is mankind’s exit from its self-incurred immaturity. […] Dare to know! “Have the courage to use your own understanding,” is thus the motto of enlightenment. [136]

The ideas quickly spread from science into other fields, such as politics, economics, religion, and ethics, where they believed the light of Reason could likewise help remake society from scratch, freeing mankind from tyranny and outdated traditions. Products of this approach included, among other things, a belief in human rights and equality, democracy and free market capitalism, a belief in an impersonal God (Deism) and atheism, and more. The approach led to both horrible excesses, such as the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution, and some of the great jewels of humanity, like the American Declaration of Independence. We will see these ideas play out in the following chapters.

Benedictus de Spinoza

The Reformation had ended the Catholic monopoly, giving rise to a plethora of radical sects with wildly different interpretations of the Bible, but few dared to question the veracity of the Bible itself. This began to change in 17th-century Netherlands, where philosophers were given much freedom to express their ideas. The country became a safe haven for exiled freethinkers, including Rene Descartes and John Locke, and also became home to a number of influential printing houses.

One of the early Dutch freethinkers was Dirck Coornhert (1522–1590), who was a firm proponent of religious freedom. In 1582, he published his Synod on the Freedom of Conscience in which he argued that religious persecution was both anti-Christian and could cause social instability. He then went a step further and argued for freedom of speech (with the exception of inciting sedition):

Freedom has always consisted chiefly in the fact that someone is allowed freely to speak his mind. It has been only the mark of tyranny that one was not allowed to speak his thoughts freely. [136]

Others began to criticize established religion. Uriel da Costa (c. 1548–1640) claimed that faith should not be based on the revealed religions but instead on reason. Juan de Prado (c. 1612–1670) claimed the revealed religions were man-made. Isaac La Peyrere (1596–1676) denied that Adam was the first man, as pagan sources mentioned civilizations older than those described by the Bible. Even more radically, Adriaen Koerbagh (1633–1669) claimed the Bible was full of contradictions and even suggested writing a version of the Bible without these obscurities. This was even a bridge too far for the Dutch, who sentenced him to ten years in prison, where he died after just a few months. His friend Lodewijk Meyer (1629–1681) applied Descartes’s method of doubt to Scripture, “rejecting in theology whatever can be rejected as doubtful and uncertain.” [259]

The most influential of these radical Dutch philosophers was Benedictus de Spinoza (1632–1677). Spinoza was one of many Jews whose ancestors had fled Portugal in fear of the Inquisition. Many of these Jews settled in Amsterdam, attracted by the promise of religious tolerance in the Netherlands (some Jews even celebrated Amsterdam as the “Dutch Jerusalem”). According to a contemporary biographer, Spinoza began to doubt his Jewish teachers at the age of fifteen and concluded that “henceforth he would work on his own and spare no effort to discover the truth himself.” [302] He soon realized this required him to look outside the Jewish community. At the age of 23, his teachers at the synagogue had become so suspicious of his ideas, that they excommunicated him for his “evil opinions and acts.” Even his family and friends were forced to break ties with him. In response, Spinoza rejected the Jewish faith.

What his “evil opinions” were is not clear, but in a text written just a few years after his excommunication, he denied the existence of an afterlife and a personal God who took an interest in his creation. Instead, he equated God with Nature (as the Stoics had done in Roman days). Similar to his contemporary Thomas Hobbes, he also believed in a fully deterministic universe, where all of creation happened by mathematical necessity. Just as for Hobbes, this also meant that human beings have no true free will. For Spinoza, a deterministic world also left no room for miracles. In fact, with God equal to nature, a supernatural event would mean God would contradict his own natural laws:

If something were to come about in nature which did not follow on the basis of its laws […] it would necessarily conflict with the order that God has set in nature for eternity through the universal laws of nature. [Therefore] a miracle, whether [it is considered to be] contrary to nature or above nature, is a mere absurdity. [259]

Albert Einstein (1879–1955) would later subscribe to Spinoza’s God:

I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals Himself in the lawful harmony of the world, not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind. [303]

Spinoza was often “accused” by his contemporaries of atheism, which was still considered an offense at the time. He vehemently denied this claim, stating he deeply revered (his version of) God.

His conception of God was further worked out in his masterpiece called Ethics (an early version of which circulated around 1663). In the first part of the book, he set out to prove the existence of God in a Cartesian manner. Inspired by Euclid’s Elements, he built his work up starting with axioms and definitions and worked out various propositions from there, as though it was a mathematical treatise. Just as with Descartes, his arguments do not hold up to modern scrutiny, yet his ideas opened doors for later thinkers. He started as follows. He defined God as a single substance with infinite attributes. He then claimed that in nature there cannot be two or more substances with the same attribute. From this, it follows that there cannot be another substance apart from God, since this hypothetical substance would have to have some attribute, but God already has all infinite attributes. Nature and God, therefore, are both equal to this one substance. He concluded:

There is only one substance in the universe; it is God; and everything else that is, is in God. [302]

In his Theological-Political Treatise (1670), Spinoza worked out his critique of the Bible. He rejected its miracles and concluded that its only divine message was its moral teachings (such as “love your neighbor”). He also stated that the Bible is no credible source of philosophy. He claimed the prophets were very pious, but they could not be trusted on matters of science. For instance, Joshua had claimed that the sun moves around the earth, on which Spinoza remarked: “Are we, I ask, bound to believe that Joshua, a soldier, was skilled in astronomy?” Crucially, without credible philosophy in the Bible, Spinoza claimed philosophy is independent of religion, and therefore he could logically claim that the freedom to philosophize could be granted without any harm to religion.

In the same work, Spinoza also made the case for democracy as the preferred political system, as it minimized abuse of power and maintained as much freedom as possible:

The end and aim of the state, in fact, is LIBERTY. [136]

This included the “freedom to philosophize and say what we think” which he set out to “defend in every way” (again, with the exception of sedition). He held this opinion not because he had much trust in the masses, but because it was necessary to allow philosophers to think as they please:

This freedom is especially necessary for advancing the arts and sciences. Only those who have a free and unprejudiced judgment can cultivate these disciplines successfully. [302]

Any regime that violated this “natural right” he considered “tyrannical.” It was also the only way for different faiths to peacefully coexist. Amsterdam, he claimed, did justice to this principle:

In this most flourishing republic and noble city [Amsterdam], men of every nation, and creed, and sect live together in the utmost harmony. [136]

Yet, eventually the censorious mob came for him too. His Treatise was banned in 1674, and a year after his death, this became true of his entire oeuvre.

Deism

These new ideas about God finally crystallized into a position called Deism. Deists asked the following questions. Why was the Bible full of inaccuracies concerning physics, astronomy, geography, and history? Why would God teach a science that humans in the 17th century would reject? And if God was wrong about science, why should we trust all his other claims? The Deists also criticized the concept of revelation. Why would God choose an obscure time and place to make himself known and reveal his will to his people? Why did God pick one desert tribe as his chosen people? And why would his message be so ambiguous that even theologians disagree about its meaning? And what about the Roman councils that voted on which books to include in the Bible and which to exclude? In many ways, the Bible seemed all too human.

The morality of the Bible also seemed dated. Why did God command the prophet Joshua to kill every last man, woman, and child of a neighboring tribe? Why did a son inherit the sins of his father? And why did God recommend putting women to death for adultery by stoning them on their father’s doorstep? Sure, Jesus rejected this practice, but why did God recommend it in the first place? Clearly, the God of scripture was, in many passages, an immoral God.

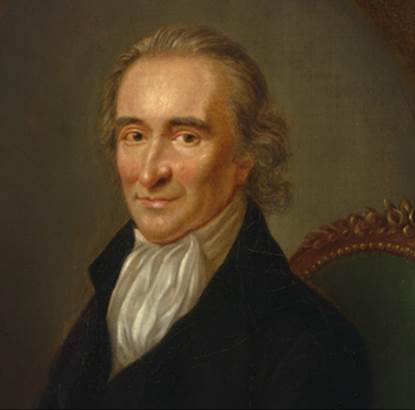

One of the more vocal critics of traditional Christianity was the British Deist Thomas Paine (1737–1809). In his masterpiece, The Age of Reason, he attacked the superstitions of the Bible with a very sharp pen. We read:

Whenever we read the obscene stories, the voluptuous debaucheries, the cruel and torturous executions, the unrelenting vindictiveness, with which more than half the Bible is filled, it would be more consistent that we called it the word of a demon, than the word of God. It is a history of wickedness, that has served to corrupt and brutalize mankind; and, for my part, I sincerely detest it, as I detest everything that is cruel. [304]

Fig. 481 – Thomas Paine by Laurent Dabos (c. 1792) (National Portrait Gallery, Britain)

Instead of needing a special book, the Deists believed God could be discovered by studying nature. Nature, they claimed, directly demonstrates God’s existence, as the order in Nature implies an intelligent lawmaker. The prime example was Newton’s universal law of gravitation, which many enlightenment thinkers saw as direct evidence of God. Newton had shown that the universe followed strict mathematical laws. It made the universe look like a brilliantly devised clock that had been set in motion at the beginning of time and would run forever without needing any repairs. In contrast, the Bible seemed to describe a universe where God had to “repair” his own creation by destroying cities with sulfur and fire, sending a mythical flood, and performing miracles. According to the Deists, this was an insult to God, as it implied that his original creation had not been good enough.

On top of this, unlike the stories from the Bible, the laws of nature can be demonstrated empirically. Where theologians can only solve disagreements by indoctrination or force, scientists can convince each other by appealing to reason and evidence.

Fig. 482 – Voltaire by Nicolas Largilière (c. 1724) (Palace of Versailles, France)

Voltaire’s God

One of the most important Deists was Voltaire (1694–1778). When studying the Bible, he, too, concluded that it was full of errors, moral shortcomings, and fables, which convinced him that it was a human product. On top of this, Voltaire was also highly critical of the religious institutions of his time, which he ruthlessly attacked in his writing with his characteristic sharp wit. He especially enjoyed mocking the priesthood for their absurd religious claims, intolerance, and corrupt leadership. Voltaire exposed these shortcomings with humor, believing that by laughing at the worldly behavior of priests, it became impossible to hold them in the same reverence ever again.

Although he did not believe in a God that has personal contact with its creatures, he did think such a concept might be necessary to keep society stable. A God who always keeps an eye on everyone, he reasoned, might just be the thing that keeps people from committing atrocious crimes. He was also worried that the concept of God might be necessary for there to be an objective standard by which to differentiate good from evil. This got him worried about the rise of atheism during his day. He therefore claimed:

If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him. [305]

Philosophical Letters

Voltaire’s polemic writing style brought him much fame and wealth, but it also got him in trouble on multiple occasions. In 1726, he insulted an aristocrat, who responded by sending over a servant to beat him up. Seeking revenge, Voltaire challenged the man to a duel, but the nobleman used his connections to get him thrown into the famous Parisian prison known as the Bastille. To get out of prison, Voltaire then negotiated an exile to England.

Voltaire left France with a bleak outlook on the world. His home land was governed by the arbitrary decisions of the totalitarian monarch Louis XIV (1638–1715), the press was heavily censored, open Protestants were condemned to death and intellectuals and artists were not respected. But when he arrived in England, he found a world far superior to his own. Impressed by what he saw, he wrote his Philosophical Letters, also known as Letters on the English Nation, in which he courageously showed his French audience how backward their lives were under the oppressive rule of Louis XIV.

Voltaire started his book describing his encounter with an English Quaker, a member of a quaint minority sect who nevertheless was free to practice his religion. Its founder, George Fox believed in the strict equality of all people. As a result, he believed that any person had the right to speak in church, both clergy and laity, men and women. In shock, Voltaire asked the Quaker if they weren’t concerned fools would speak in church. The Quaker agreed this was sometimes the case, but stated they had no way of knowing beforehand which person would be inspired by the Holy Spirit. When George Fox was brought before a judge for his beliefs, Voltaire tells us, his principle of equality also made him refuse to take off his leather hat and swear an oath. As a result, Fox “was sent to the […] madhouse to be whipped.” Instead of resisting, he “begged [his torturer] to give him a few more lashes for the good of his soul […] for which he thanked them cordially. […] He then began to preach to them; at first they laughed; then they listened; [and] those who had whipped him became his first disciples.” [306]

Although Voltaire did not agree with him on matters of theology, he recognized the advantage of allowing everybody to believe as they choose. With his characteristic wit, he wrote:

This is the country of sects. An Englishman, being a free man, goes to Heaven by whatever path he chooses. [306]

The Church of England also functioned better than its French counterpart. The French often filled the positions in their Church with sons of aristocrats, who were known to exploit their power, hoard money, and—as Voltaire liked to point out—indulge in women and alcohol. In contrast, “all churchmen [in England] are educated in the Universities of Oxford or Cambridge, far from the corruption of the capital [and] they are called to the honor of the church only after many years, at the age when […] their ambition has nothing to feed upon.” Voltaire did have to admit that members of the Church of England often got preferential treatment and priests of different branches of Christianity still “detested one another,” but other than that, “all sects [were] welcome there and lived together comfortably enough.” [306]

This freedom, Voltaire noted, was gained the hard way. The British too used to “hang each other” over religious quarrels and “paid heavily to establish their liberty,” but over time they “seemed to have gained wisdom at their own expense, and I do not see in them any further longing to cut one another’s throats for the sake of a syllogism.”

Voltaire noticed that the fruits of religious toleration were especially apparent in the Royal Exchange of London, where the mutually rewarding practice of trade brought people together:

Enter into the Royal Exchange of London, a place more respectable than many courts, in which deputies from all nations assemble for the advantage of mankind. There the Jew, the Muslim, and the Christian bargain with one another as if they were of the same religion, and bestow the name of infidel on bankrupts only. [...] Was there in London but one religion, despotism might be apprehended; if two only, they would seek to cut each other’s throats; but as there are at least thirty, they live together in peace and happiness. [307]

In contrast, the French nobility had disdain for merchants. This, according to Voltaire, was a big mistake:

I […] do not know which is more useful to the State: a nobleman in a powered wig who knows exactly when the king arises and when he retires, and who gives himself airs of greatness while he plays the slave in the antechamber of a minister; or a merchant who enriches his country, who sends orders from his counting house to Surat and Cairo, and contributes to the wellbeing of the world. [306]

Freedom was also the central word in British politics. Over the centuries, the British had fought hard to attain liberty, which resulted in England becoming a constitutional monarchy:

The English nation is the only one on earth that has managed to control the power of kings by resisting them, […] and where the common people share power without disorder.

Voltaire was especially impressed by British science, including Francis Bacon’s invention of the scientific method. Before Bacon, he claimed, “chance alone produced most […] inventions,” but now a method was found by which philosophers could systematically “unearth” scientific truths like a “buried treasure,” leading to a plethora of new inventions and discoveries. Referring to John Locke’s admission that human knowledge was limited to what can be known through the senses, he famously stated:

I am proud to be as ignorant as John Locke on this matter. [308]

Voltaire’s greatest role model was Isaac Newton, whose work he would later help popularize in France. Voltaire considered Newton’s genius as practically divine and considered him a greater hero than even Caesar or Alexander the Great. Whereas these men conquered the world, Newton enlightened it:

If true greatness consists in having received from Heaven a powerful intelligence and in using that intelligence to enlighten oneself and others, then a man like Mr. Newton, whom one might scarcely hope to encounter in the course of ten centuries, truly should be deemed great;

And these politicians and conquerors, who can be found in any century, are no more than illustrious villains. We owe respect to him who influences the mind by the means of truth, not to those who make slaves by violence, to him who understands the Universe, not to those who disfigure it. [306]

Voltaire was present at Newton’s grand funeral in Westminster Abbey, which made a lasting impression on him. Coming from a country where only the aristocracy and the clergy occupied positions of high esteem, Voltaire was amazed to find that the English buried a scientist with the honors of a king. Later in his life, he recalled:

I have seen a professor of mathematics, only because he was great in his vocation, buried like a king who had done good to his subjects. [309]

In his Letters on the English Nation, he wrote about the event:

The chief men of the nation vied for the honor of carrying the pall in his funeral procession. [306]

Similarly, the great poet Alexander Pope (1688–1744) was esteemed more than even the prime minister:

What chiefly encourages the arts in England is the esteem they receive: the portrait of the Prime Minister hangs over the mantelpiece of his office, but I have seen Mr. Pope’s portrait in 20 houses.

In contrast, Voltaire noted, the French philosopher René Descartes had “left France, because he sought truth, which was persecuted by the miserable philosophy of the Scholastics.”

In short, England was tolerant, secular, lawful, free, and commercial, while France was intolerant, anti-commercial, aristocratic, and despotic. According to Voltaire, this explained why England was a more prosperous and peaceful society.

When Voltaire was allowed to return to France, his Philosophical Letters became a bestseller. Understandably, the French authorities were not thrilled about this and drove Voltaire out of Paris. He was offered a place to stay at the estate of Emilie du Chatelet (1706–1749), a respected Newtonian who had translated Newton’s Principia Mathematica into French. The two became friends, lovers, and intellectual collaborators. Tragically, she died in 1749 while giving birth to a child from another lover.

After her death, Voltaire accepted an invitation to live at the court of King Frederick II of Prussia (1712 – 1786) under the assumption that he would be able to advise the king on implementing some of his ideas about humane government. Yet he soon found out that the king was not interested in his advice, but simply used him as an adornment to his court. Ashamed and angry, Voltaire headed back home, but not before stealing the king’s terrible love poetry, which he intended to publish in France. When Frederick noticed his poems were missing, he stopped Voltaire at the border, after which he had to spend five weeks in prison.

Fig. 483 – The Lisbon Earthquake (1755)

The Lisbon earthquake

Voltaire’s greatest work, Candide, was written primarily as a satirical rebuttal of ideas by the otherwise brilliant German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) and the equally brilliant philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778). Leibniz had attempted to explain how it was possible for senseless suffering to exist in a world ruled by a loving and omnipotent God. To solve the paradox, Leibniz proposed an idea called philosophical optimism. He argued that since nothing outside of God is perfect, it is logically necessary for any creation to have some flaws. Leibniz then attempted to prove that the universe God actually created, was, however flawed, still the “best of all possible worlds.”

Voltaire responded to Leibniz with his Poem on the Lisbon Earthquake, in which he showed that his position was both inhumane and totally irrelevant to those who are actually suffering. To prove his point, he referred to a devastating earthquake that struck Lisbon in 1755, which led to tens of thousands of deaths and destroyed a large part of the city. What philosopher would tell a mother with a dying child in her arms that this is, in fact, the “best of all possible worlds”? According to Voltaire, we simply have to admit that pain, injustice, and cruelty are very real and can’t possibly be reconciled with a loving and omnipotent God. The only sensible response to this fact of life, Voltaire claimed, is not to philosophize it away but to give love and attention to those who are suffering.

Rousseau had another explanation for the earthquake. He believed that God was not responsible for evil, but that it was man’s own fault for creating artificial cities, while God had meant us to live in a more natural state:

Concede, for example, that it was hardly nature that there brought together twenty-thousand houses of six or seven stories. If the residents of this large city had been more evenly dispersed and less densely housed, the losses would have been fewer or perhaps none at all. [310]

Voltaire wrote Candide to further work out his opposition to both views. The book was written in a literary genre he had developed himself, known as the philosophical tale (“conte philosophique”), in which he used a fictional story to prove a philosophical point. The story revolved around his main character, Candide, and Professor Pangloss, a self-proclaimed Leibnizian optimist. With his lighthearted humor, Voltaire had Pangloss maintain his belief in the “best possible world” in the face of many horrors that befell him and his friends, including disease, torture, and much more. En route to Lisbon by boat, one of their friends died in a storm, which Pangloss explained away by stating that the Lisbon harbor was created in order for him to drown. Even when the Lisbon earthquake hit, Pangloss persisted in his optimism. After many more horrifying stories, Candide met an old Turk, who claimed to live a good life through hard work cultivating his land with his family. Inspired by his peaceful life, Candide decided to stop philosophizing about things too big for human beings to understand. Instead, he made a commitment to work hard to make his life bearable by focusing on his daily activities. When Pangloss again suggests that all the horrors happened for a reason, Candide responds:

That is well said, but we must cultivate our garden. [311]

This, Voltaire claimed, is the only antidote to our despair.

Candide marked a crucial turn in Voltaire’s career from abstract philosopher to humanistic activist. Using his pen as a weapon, he courageously attacked the great injustices of his time, fighting against unjust wars, torture, slavery, serfdom, religious intolerance, inequality before the law, censorship, and much more. Leveraging his enormous fame, he pressured bad actors to change their ways, and he celebrated those who acted with humanity.

Bach and Mozart

During the Age of Enlightenment, music theory also finally reached its mature phase. The greatest composer of this era is now often considered to be Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), although many of his contemporaries considered his music to be too complicated and too learned. Much of Bach’s music, which belonged to the Baroque style, is intricate and complex, but at the same time orderly, to the point of mathematical.

In some of his pieces, Bach presents us with a simple melodic line of just a few notes, which he then starts to play with, repeating it over and over, but each time with slight variations, taking us on a journey through various keys, which required a genius and almost mathematical understanding of the similarities and differences between chords. A great example is his Prelude No. 1 from his Well-tempered Clavier. The theme starts in a pleasant-sounding key suggestive of our comfort zone, but then moves to more jarring chords which make us feel slightly on edge, heightening our focus, until finally we let out a sigh of relief when he returns the melody home.

Fig. 484 – First page of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, showing Prelude No. 1 (1722)

The most emblematic composer of the second half of the 18th century was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791), who, like many of the great composers of the time, lived in Vienna. Mozart’s music, which belongs to the Classical style, was much less contrived and intellectual, making it sound more natural and tuneful. As a result, it was easier to listen to and therefore appealed to a greater audience. His simplicity, however, was deceiving, as he retained the great advances in music theory. Great examples of his music are Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, Symphony No. 40 in G minor, and his Requiem. In line with Enlightenment philosophy, Classical music had a more international feel. It aimed to convey a universal notion of beauty, devoid of regional or folkish influences.