In the 17th century, the Dutch took over the lead from the Portuguese and the Spanish as the most powerful nation on Earth. Dutch territory had been in Spanish hands since 1556, but this started to change in 1568 when the Dutch elites rebelled under the leadership of William of Orange in what came to be known as the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648). William and his companions were driven by a new ideal of religious toleration, seeking an end to the persecution of heretics by the Spanish Catholics. After chasing out the Spaniards, the Netherlands sought a new king, but when no proper candidate was found, they became a republic, ruled by representatives from all the Dutch provinces.

In this period, the Netherlands also became the most commercially oriented nation in the world. To facilitate trade, they created the Dutch East India Company (the VOC), which built thousands of ships to sail to the East Indies. The company also sold stocks to the general public, which led to the development of the world’s first stock exchange in Amsterdam.

Religious toleration

For centuries, it was assumed that the coexistence of different religions within a single state would inevitably result in conflict, potentially leading to civil war and the disintegration of the nation. Elites were therefore eager to stamp out budding religious sects, yet during the Reformation, these groups became so prevalent that religious oppression and violence became the order of the day. In some parts of Europe, the population got so sick of the endless religious strife, that they became willing to lay aside their religious differences.

An early compromise was the Peace of Augsburg (1555), which sought to bring peace to the states of the Holy Roman Empire. In the treaty, the rulers of each state agreed to tolerate each other’s religion to prevent wars, while simultaneously demanding that all subjects partake in the religion of their lord, thus preventing social disintegration. The principle was famously summarized as “whose realm, his religion”. Subjects who were unhappy with the religion of their ruler were free to move to another state.

The Netherlands in the 16th century took a different route. Courtesy of the Reformation, the country had also become religiously diverse, comprising a Catholic majority and an elite more inclined towards the humanism of Erasmus and the Protestantism of Calvin. While the strict teachings of Calvin allowed little room for differences of opinion, Erasmus had been an early promoter of religious toleration. He strongly objected to quibbles about petty theological differences and also vehemently opposed religious coercion and persecution. Instead, he claimed, different Christian faiths should be able to peacefully coexist, while agreement should be sought through dialogue alone.

The ideas of religious toleration matched well with the emergence of a wealthy merchant class in the Netherlands, which became well-represented in local politics. Merchants generally prefer to maximize their freedom to pursue their economic interests. They simply want to sell their products to the highest bidder, no matter someone’s political or religious beliefs.

Together, these elements gave the Dutch a unique appetite for what they called freedom of conscience—meaning the right to hold the beliefs of one’s own choice. This intensified when King Philip II (1527–1598), the Spanish Catholic monarch who ruled over the Netherlands, aimed to stamp out the Protestant faith to stabilize his realm. This was a great shock to the Dutch, as persecutions had been rare in the Netherlands in recent decades. Amsterdam, for instance, had not issued a single death sentence for heresy since 1533. It had become a common belief in the Netherlands, that a heretic, whatever his beliefs might be, does not deserve the death penalty. Philip, however, was still of the old view that religious plurality was dangerous for the survival of the state.

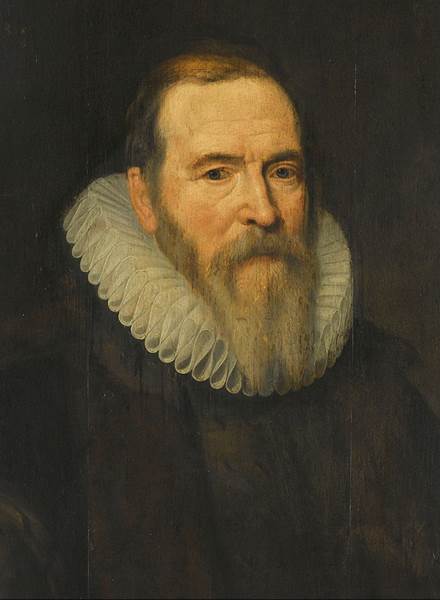

Fig. 491 – A portrait of William of Orange by Anthonie Mor (c. 1554) (Schloss Wilhelmshohe, German)

The loudest voices of resistance came from the Dutch nobles (the “edelen”), led by William of Orange (1533–1584). Although he is now often seen as the quintessential Dutchman, he actually came from the German Nassau family, did not speak Dutch fluently, and was appointed by the Spanish Crown to govern over a number of Dutch provinces. He got his name Orange after inheriting the independent principality of Orange in France. In line with Erasmus, he believed in freedom of conscience.

The Calvinists resisted in their own way. In the south of the Netherlands (now Belgium) they began to defy the law by preaching and singing in public. In one instance, thousands of men armed with sticks came to hear an illegal sermon and even freed two prisoners who were set to be publicly burned. After another sermon, the listeners got so riled up that they entered a monastery and began to demolish its statues. This movement culminated in the beeldenstorm (“storm of statues,” see Fig. 439).

The Dutch Republic

In 1566, two hundred Dutch nobles presented a petition called the Covenant of the Nobles to Margaret of Parma (1522–1586), the regent of the Netherlands, asking for a suspension of persecutions, acceptance of public sermons, and freedom of conscience. If this was not granted, they claimed, rebellion would be imminent. One of Margaret’s advisors rejected their claims, calling the nobles “only beggars (geuzen),” which the rebels proudly adopted as their honorary title. At first, Margaret gave in, but she soon ignored the petition, which for William meant war. To prepare, he left for Germany with his followers. Other prominent nobles, such as Lamoraal van Egmont (1522–1568) and Filips van Horne (1524–1568), rejected William’s call to violence and stayed in the Netherlands.

In response to William’s insubordination, Spain sent the Duke of Alva (1507–1582), who was ordered to bring the Dutch back in line with a heavy hand. He established what came to be known as the Blood Council, which oversaw more than a thousand executions. Egmont and Horne, who had deemed themselves safe because of their rejection of violence, were publicly beheaded at the Grand Market in Brussels.

William of Orange first attempted an attack over land, but he turned out no match for the Spaniards. With all odds against him, he nevertheless persisted. In his Justification of the Prince of Orange (possibly written by his advisor), he expressed his faith that God would help him succeed. On the cover he quoted Psalm 37, which states:

The wicked lie in wait for the righteous, intent on putting them to death; but the Lord will not leave them in the power of the wicked.

Fig. 492 – The capture of Den Briel by Frans Hogenberg (c. 1615) (Rijksmuseum, The Netherlands)

The Dutch won their first meaningful victories at sea. The true watershed moment occurred in 1572 when a group of rebel sailors, known as the watergeuzen (“sea beggars”) sailed on Den Briel, a small town near Rotterdam. Under the leadership of Admiral Lumey (1542–1578), they took over the town and hanged 19 Catholic priests in a peat shed just outside the city. The sea beggars operated in the name of William of Orange, but in reality were a rather unruly bunch, consisting not only of religious exiles but also bandits and adventurers. Other than William of Orange, who rebelled mainly “for the sake of freedom,” the sea beggars were Calvinists who had joined “for the sake of religion.”

In the same year, the Council of the States of Holland (representing the most influential Dutch province) convened without authorization from its Spanish rulers, and recognized William of Orange as their leader, or “stadholder”. In 1576, they signed the Union of Delft, which granted the provinces Holland and Zeeland freedom of conscience. William also hoped to attain freedom for the people to exercise their religion in public, but the Calvinists put a stop to this. Instead, all churches fell into their hands. William did manage to prevent the creation of a Calvinist state, where church and state would completely overlap. He did become a member of the Calvinist church, likely for political reasons.

In 1579, the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands united by signing the Union of Utrecht. The treaty contained a famous promise of religious toleration:

Every individual should remain free in his religion, and no man should be molested or questioned on the subject of divine worship. [302]

It would take long, however, before this promise was honored, since in the 1580s, public worship by Catholics was outlawed in all the provinces (although in practice, they could often convene in clandestine churches that appeared like regular houses from the outside).

Two years later, the Staten-Generaal, the Dutch assembly with representatives from the provinces, signed the Act of Abjuration (“Plakkaat van Verlatinghe”)—the Dutch declaration of independence. According to the document, “God did not create the people as slaves to their prince, to obey his commands, whether right or wrong, but rather the prince for the sake of the subjects […], to govern them according to equity, to love and support them as a father his children or a shepherd his flock, and even at the hazard of life to defend and preserve them.” [338] A ruler who fails to do this, has become a tyrant, and thereby forfeits his right to rule. We read:

And when he does not behave thus, but, on the contrary, oppresses them, seeking opportunities to infringe their ancient customs and privileges, exacting from them slavish compliance, then he is no longer a prince, but a tyrant, and the subjects are to consider him in no other view. And particularly when this is done deliberately, unauthorized by the states, they may not only disallow his authority, but legally proceed to the choice of another prince for their defense. This is the only method left for subjects whose humble petitions and remonstrances could never soften their prince or dissuade him from his tyrannical proceedings; and this is what the law of nature dictates for the defense of liberty, which we ought to transmit to posterity, even at the hazard of our lives. [338]

As soon as King Philip ascended the throne, the text then states, he had taken away the liberties of the Dutch, enslaving them under Spanish rule. This gave the Dutch the right to take back their freedom.

In the 16th century, it was commonly believed that royal families had been ordained by God to rule mankind. This was also the opinion of William of Orange, who had no intention to keep the power over the Netherlands for himself. Instead, the Dutch looked to France and England for overlords, but all candidates were either deemed unsuitable or had no interest. But then, in 1584, William was assassinated by a shot in the chest. His murderer had been driven both by his own political convictions and by the promise of a large reward offered by King Philip.

In 1588, when all negotiations with potential rulers had failed, the seven northern provinces formed the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. But this did not mean they had won the war. The Dutch only began to win significant battles on land under the stadholder Maurits of Orange (1567–1625), who conquered many Dutch cities. The Spanish finally accepted Dutch independence in 1648 when they signed the Treaty of Munster, leading to the establishment of the first fully independent Dutch republic.

The VOC

In the 1590s, the Dutch began to build long-distance ships for trade, in competition with Spain and Portugal. Since these ships were expensive, they were usually only commissioned by kings, but as many Dutch merchants had accumulated enormous wealth, they were able to pool their money together to form shipbuilding companies. Economically speaking, this allowed relatively small investors to put their money to good use, instead of letting it remain idle in their bank accounts. The first ships only got as far as Africa, but in 1595 a company called Company van Verre (“Company from Afar”), founded by nine merchants from Amsterdam, reached Indonesia. The trip was not very profitable, but it proved the trip was possible. In the next seven years, 80 more ships left for Indonesia, most of which generated large profits.

As competition between the Dutch companies grew and grew, the leading Dutch statesman Johan van Oldenbarnevelt (1547–1619) thought it beneficial to combine their efforts into one huge company that would instead compete with Portugal. This happened in 1602, when the government issued a charter (“octrooi”) which allowed for the fusion of all existing shipbuilding companies into one megacorporation known as the Dutch East India Company (abbreviated in Dutch as VOC). In time, they would build thousands of ships, dwarfing their Portuguese and Spanish competitors. The company also received permission from the Dutch government to wage war, negotiate with local leaders, settle disputes, and establish colonies, giving them powers usually associated with a state. Unlike earlier companies, they also employed soldiers and built forts, with the intent of creating a permanent presence in the east. As a result, the VOC made the Netherlands the foremost military and economic power in the world—an especially incredible achievement considering the small size of the country. Suggestive of their enormous wealth, the Dutch investments into the VOC outdid their main competitor—the English East India Company—by a factor of ten. As a result of the influx of wealth, poverty mostly disappeared from the Netherlands and where it did still exist there were attempts to remediate it through public funds and charity.

When the Dutch set out to sea, the Spanish and the Portuguese had already divided up the world between them with the Treaty of Tordesillas. Obviously, the Dutch had no intention of abiding by their rules. To legitimize their encroachment on Spanish and Portuguese trade routes, they advocated for free trade. A great proponent of this view was the Dutch humanist Hugo de Groot (1583–1645), who wrote Mare Liberum (“The Freedom of the Seas”) on behalf of the VOC. The work is considered the foundational text of international law regarding the sea. De Groot argued that the sea was international territory and that all nations should be free to use it. As the sea was more like air than land, he reasoned, it should be common property to all. He wrote that it was the most “unimpeachable axiom of the Law of Nations” that “every nation is free to travel to every other nation, and to trade with it.” [339]

The VOC soon managed to expel the Portuguese from Spice Island (the Moluccas) and established colonies in Indonesia, Taiwan, Sri Lanka, and South-Africa. The VOC did not dare colonize Japan, but they did manage to gain a monopoly on trade with them. They were allowed to establish a trading post on an artificial island in the harbor of Nagasaki, where the Japanese decided which commodities were offered and at what price.

Fig. 493 – VOC ships by Abraham Stock (c. 1698)

It took the VOC a lot of effort to get a foothold in Indonesia, which would become their most important colony. The VOC governor Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1587–1629) finally managed to stabilize the colony. He also established Batavia¸ now Jakarta, which functioned as a central hub from which to coordinate their affairs in Asia. Although considered a hero in his time, he was also ruthless. When taking control of the Banda Islands of Indonesia, he had thousands of natives killed or deported to Batavia.

Fig. 494 – Hugo de Groot by Michiel van Mierevelt (1631) (Prinsenhof, The Netherlands)

In 1621, the Dutch government issued a charter for a second company, the Dutch West India Company (WIC), which colonized Suriname, the Antilles, and for a few decades north-eastern Brazil. Although overall the company was not very successful (it had relatively few investors and went bankrupt twice), it became for a short while the largest player in the transatlantic slave trade. In total it shipped an estimated 250,000 slaves to America and accounted for roughly 5% of the Dutch economy.

Given that the Dutch were most successful at sea, their greatest heroes were often sea captains. One of these heroes was Piet Hein (1577–1629), an admiral in service of the WIC. In 1628, near Cuba, he famously captured a Spanish silver fleet. Only two shots were fired, after which they took possession of the silver.

Fig. 495 – Johan van Oldenbarnevelt by Michiel van Mierevelt (1631) (Rijksmuseum, The Netherlands)

New Amsterdam

In 1609, the VOC hired the British explorer Henry Hudson (c. 1565–1611) to look for a possible Northeast Passage to India (by sailing along the coastline of Russia). When he encountered harsh storms, he reversed course and instead looked for a Northwest Passage. He eventually reached the North American coast, where he sailed up what is now called the Hudson River, hoping it might be a passage to the Pacific Ocean. When he found this was not the case, he gave up and went back home. The territory he discovered, however, would later be home to one of the greatest financial hubs in world history. Things didn’t end well for Hudson. On a later journey, his crew mutinied, setting him adrift on a small boat, never to be seen again.

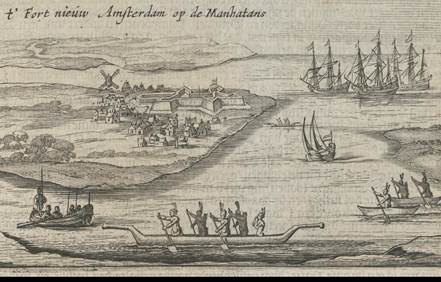

In 1614, the Dutch established fur trading posts on Manhattan (“Island of many hills”) and further upriver at Fort Orange (now called Albany). Ten years later, the WIC bought Manhattan for goods worth about 60 guilders (a thousand dollars in today’s currency) and established a settlement called New Amsterdam, which became the capital of New Netherland (located right between the early English colonies). Fig. 497 shows an early map of New Amsterdam. On the tip of the island, we see Fort Amsterdam next to a Dutch windmill. On the east side we see a defensive wall, located on what is now Wall Street. Two other settlements in the area were given the Dutch names Haarlem (Harlem) and Breukelen (Brooklyn).

As New Netherland was primarily driven by commercial rather than religious interests, it quickly became the most culturally and ethnically diverse settlement in North America, attracting a wide variety of emigrants who valued its practice of religious toleration, including Spanish and German Jews, French Protestants (Huguenots), and English Puritans and Catholics. There were even Muslims in New Amsterdam.

Fig. 496 – New Amsterdam on Manhattan, New York (1651). Notice Fort Amsterdam and a Dutch windmill (New York Library, United States)

Fig. 497 – The Castello Plan by Jacques Cortelyou showing an early city map of New Amsterdam, located in what is now the Financial District of Lower Manhattan (a copy of an original map from c. 1660)

Over the course of the 17th century, the English became the main competitor of the Dutch. Their ships confronted each other during the Anglo-Dutch Wars in the second half of the 17th century, which were mainly fought over access to the main sea routes out of Western Europe (see Fig. 498). In most cases, the Dutch were victorious. In one infamous incident in 1667, Admiral Michiel de Ruyter (1607–1667), another heroic sea captain, boldly sailed into English territory—sailing all the way down the Medway River to Chatham—where he destroyed an English fleet.

In 1664, a peace treaty between England and the Netherlands put New Amsterdam in the hands of the English, which they renamed New York (after the Duke of York, who would later become King James II), while the Dutch gained control over Surinam in South America, with its valuable sugar plantations.

Fig. 498 – The Anglo-Dutch Wars by Reinier Nooms (c. 1660) (Rijksmuseum, The Netherlands)

The stock market

A large part of Dutch success was their revolutionary financial system. Already in the 16th century, the Dutch government developed a system of public debt that allowed them to sell bonds to the public at low interest rates, which made it much easier to fund large projects, such as wars. Since finance is often a deciding factor in war, it often allowed them to get the upper hand.

Another great invention was the stock market. The VOC became the first company in the world to issue stocks in the modern sense. Simpler short-term stocks had existed earlier, for instance in China during the Tang and Song dynasties and also in Genoa and Venice in the Late Middle Ages, but trade in these stocks was rare. These companies also formed around a single project (such as the building of one fleet) and were disbanded when this project was completed, after which the goods were auctioned and the shareholders were paid out. The English East India Company, which was established two years before the VOC, also issued shares, but these too were only valid for the duration of a single project.

In Amsterdam, the stock market became an entire world of its own. According to the Jewish financial expert Joseph Penso de la Vega (1650–1692), who wrote the first book on the stock market called Confusion of Confusions (1688), “there wasn’t a single place [in Amsterdam] where one didn’t talk about stocks.” [340] De la Vega described the stock market as a rough place, where people would often shout and where fights were not uncommon. Outsiders who had no interest in entering this “battle arena” would hire a middleman, now called a market maker, who would trade for them for a small fee. In personal letters we find the same excitement over the stock trade. Hoping to make a quick buck, we read still common statements, such as: “It can’t hurt to buy some stock now. It is probable the stock price will increase a lot.” [340]

The charter of the VOC, which was issued by the Staten-Generaal in 1602, made stocks available to the general public, stating that “all residents of these lands may participate in this Company.” [340] In total, they collected over 6.5 million guilders as its starting capital, which is equivalent to 100 million dollars today, from over a thousand investors. The VOC never opened another investment round. This is remarkable, as they often took out loans, suggesting they were in need of capital. It is most likely this option simply didn’t occur to them.

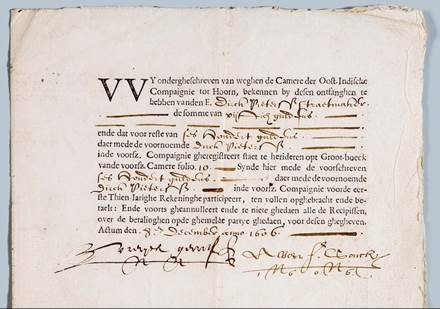

Fig. 499 – Receipt of a stock payment by Dirck Pieterszoon Straetmaker for a payment of 50 guilders of a total of 600 guilders (Capital Amsterdam Foundation, The Netherlands)

The charter also mentioned that “transfers [of shares] could be made with the bookkeeper [of the VOC].” At first, this occurred in the house of one of the leaders of the company, but later they moved to the East-India House, designed in 1606 by the famous architect Hendrick de Keyser (1565–1621). When people bought stock, they received a receipt from the bookkeeper (see Fig. 499). These receipts are often advertised as the oldest stocks, but they were actually just receipts with no inherent value and could not be traded. A stock trade was only valid if recorded in a book at the accountant’s office. According to this book, the first stock was sold already in 1603, when the first part of the investment had to be paid. The owner could not afford the stock and therefore sold it with an estimated profit of about 5%.

The term of the VOC charter was 21 years, but it was eventually extended by the government to almost two centuries. During this time, the profits would go straight back into the company, a strategy unheard of at the time. In good years, the company did pay out dividends to the shareholders. As early as 1618, the total amount of dividends paid out was already 162.5%. The 1630s were especially successful. Between 1633 and 1643, the stocks rose 250% in value, while the VOC also paid out 322.5% in dividends. In 1637, the stock market value of the VOC reached its highest point of 78 million guilders. Converted to today, this corresponds to about 7 trillion euros, making it the highest stock market value of a company ever.

Initially, the shareholders were not informed on how the company was doing. In time, anonymous writers wrote pamphlets, accusing the VOC leaders of using insider information to make a profit off the back of the shareholders. One of the authors, later identified as Simon van Middelgeest, demanded the VOC opened its book every year to give an account of its financial situation. Promises were made for a more transparent bookkeeping, but little came of it. As a result, stock traders were solely reliant on external sources of information about the success of the VOC. Rumors, for instance about a fleet being on its way home with valuable goods, got people to frantically buy more stock, which caused the stock price to rise. Especially traders with connections abroad could use their information to their advantage.

Fig. 500 – The Old Exchange of Amsterdam by Job Berckheyde (c. 1670) (Boijmans Museum, The Netherlands)

While the bookkeeper of the VOC made official records of stock trades, the actual sale of stocks took place on the New Bridge in Amsterdam. On bad weather days, they were allowed to enter Saint Olof’s Chapel. Before 1602, the chapel was used for the sale of goods and loans, but when the VOC was established, stocks were added, making it the world’s first stock exchange. In 1611, the traders transferred to the Amsterdam Stock Exchange (“De Beurs”), also designed by Hendrick Keyser. The building looked like a walled market square surrounded by 42 numbered columns, each corresponding to a different type of trade (see Fig. 500). One visitor wrote he saw there “a great multitude, thousands of people; from many different peoples from all the regions of the world.” [340]

In the stock market, traders also sold and bought futures, where a buyer agrees to buy a stock at a fixed date for a fixed price, hoping the market price of the stock had gone up in the meantime. As going to the bookkeeper to record a trade was rather cumbersome and costly, traders would usually simply settle the price difference at the expiration date of the future. These indirect transactions are now called derivatives.

Amsterdam’s Sephardic Jews, who had fled Portugal and Spain and moved to Amsterdam for its relatively tolerant atmosphere, became especially adept in the stock trade. Many Jews had moved into the finance business as they were not allowed to enter professions with a guild structure. They quickly became successful, especially since they often had connections with the Jewish diaspora all over Europe, which made it easier to predict the rise or fall of the stock price.

Interestingly, only two companies, the VOC and the WIC, sold stock during the Dutch Golden Age. This had a number of reasons. First of all, there was less need for large investments in the 17th century, as expensive machinery still did not exist. Another problem was that a stock company required permission from the Staten-Generaal, who would then also demand significant involvement in the company. This situation improved in London in 1690, two years after the Dutch King William III became king of England, bringing with him both the Dutch system of national public debt and the stock market (thereby effectively giving England everything it needed to quickly outcompete the tiny Dutch nation). Within a few years, 25 companies entered the English stock market, mostly for the war industry. Almost all of them would not make it till the end of the century, but they did gain experience on how to raise capital from the general public to finance large projects. Problematically, there were even vacuous companies with zero plans, who just capitalized on the fear of missing out.

Gaming the system

Some stock traders also figured out how to game the system in order to get rich. Isaac de Maire (c. 1558–1624), one of the founders of the VOC and its biggest investor, sold futures, even more than he had according to the books, and then spread false rumors causing the stock price to fall, allowing him to make a great profit. The selling of stock one didn’t actually own was eventually prohibited, becoming the first government regulation on stocks. The first bookkeeper of the VOC, Barent Lampe, also got in trouble when he helped a man named Hans Bouwer make payouts to other accounts, without subtracting it from his own. When the scheme was figured out, both men fled from the city.

Fig. 501 – A sheet from a tulip book, possible a sales catalogue, by Jacob Marrel (c. 1640)

Tulip mania

The 17th century also saw a few market crashes. One of them occurred in 1672. The previous year had been wildly successful, and as a result, many people bought stocks in hopes for another good year, but then the republic came under attack by France, England, Cologne, and Munster. As a result, the stock price nearly halved, although it soon recovered. In 1688, there was another crash, based on rumors the republic would go to war with England, but this too quickly subsided.

The greatest financial bubble of the 17th century occurred not in the stock trade, but in the sale of tulips. Tulips had been brought over from the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century and generated much interest in the Netherlands. Owing to their immense popularity, combined with their scarcity, the price of tulips kept rising. For quite a while, traders were making a good living just by buying tulips and selling them a short while later. The more success stories spread, the more people jumped in, not wanting to miss out. Soon, this caused the price of tulips to completely disconnect from the actual worth of these rather useless and perishable bulbs. In 1636, this devolved into proper tulip mania, with prices rising twenty-fold. In one instance, a single bulb was sold for 5200 guilders, while 1000 guilders could get you a nice house in a major city in the Netherlands. When the bubble finally burst, the last to hold on to these bulbs lost a fortune.

The Dutch Golden Age

The newly gained wealth, the contagious spirit of entrepreneurship, and the new military confidence of the Dutch Golden Age also proved fertile ground for world-class philosophers, lawyers, scientists, engineers, and artists. In 1612, merchants and politicians from Amsterdam set out to expand Dutch territory by “creating” new land by draining a large lake known as the Beemster. To do this, they first built a 38-kilometer-long dam around the lake, after which engineer Jan Leeghwater (1575–1650) placed 43 windmills to pump out the water. This method was used time and again over the centuries, greatly expanding Dutch territory (see Fig. 502)

In the sciences, Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) invented the pendulum clock, which became the most accurate timekeeper for almost 300 years. He also was the first to demonstrate that light has wave-like properties and derived the formula for the force necessary to keep an object in circular motion (the centripetal force), which became essential for Newton’s theory of gravitation.

Of course, the Dutch were also known for their paintings. It is estimated that about 5 million paintings were made in 17th-century Netherlands, many also affordable for the lower class. Famous painters such as Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), Frans Hals (c. 1582–1666), and Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) made history with their unprecedented realism and their ability to create believable characters that could make an intimate connection with the viewer.

Fig. 503 - Self-portrait of Rembrandt van Rijn (c. 1665) (Kenwood House, Britain)

Fig. 504 – The Milkmaid by Johannes Vermeer (c. 1658) (Rijksmuseum, The Netherlands)