Over the span of five hundred years, England developed the most impressive legal system in the history of the world—the Common Law. The first steps were taken in 1215, when the barons of England forced the failing King John to sign the Magna Carta, in which he agreed to levy taxes only with their consent. In the same century, the British Parliament was established, which after a bloody coup also allowed commoners in their midst.

During the Age of Enlightenment, the philosopher John Locke declared that all men were gifted natural rights by God and that among them was the right to give consent to their rulers. Any ruler who opposed this right, he claimed, could be justly toppled. Inspired by his ideas, a group of noblemen invited the Dutch leader William III of Orange to invade England. He took over without a fight in what has been called the Glorious Revolution. Once in charge, William signed the Bill of Rights, which turned England into a constitutional monarchy.

Starting in the 17th century, the British also gained dominance at sea. In 1600, they founded the East India Company, which over time took control over India. Over the centuries, the British managed to colonize a staggering 25% of the globe, forming the British Empire.

The British also developed better clocks that worked at sea, allowing sailors to determine their coordinates and reach their destinations without guesswork. They also undertook expeditions with the express purpose of settling scientific questions. The archetypal captain of this endeavor was James Cook, who mapped the world with unprecedented accuracy.

The Magna Carta

Starting as early as 1215, England embarked on a long but fruitful path toward freedom and justice. In that year, the barons of England got so fed up with King John (1166–1216) that they forced him to sign the Magna Carta. Revolutionary, the document implied that even the king was subject to the law, as it required him to seek the consent of the barons when levying taxes. The document then promised to protect “all free men” from illegal imprisonment:

No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land. [341]

Fig. 505 – The Magna Carta (The British Library)

The 13th century also saw the establishment of the English Parliament (derived from the French “parler,” meaning “to speak”). It grew out of a custom among the Norman kings of England, who called a council of barons and bishops three times a year. The role of Parliament greatly expanded in 1258, when the Earl of Leicester, Simon de Montfort (c. 1205–1265), became fed up with the misrule of Henry III (1207–1272). With the help of other members of Parliament, he forced the king to agree to the Provisions of Oxford, which granted Parliament the right to approve new taxes, allowing them to indirectly veto the king’s plans. The document also granted Parliament the right to convene to “discuss the common business of the realm.” [342] A few years later, Henry broke the terms of the provision. The result was a civil war. Montfort emerged victorious, took the king prisoner, and declared himself the de facto ruler of England. Once in charge, he showed himself to be a true man of the people by inviting commoners to Parliament. Montfort was defeated a year later, but Henry III had learned his lesson and continued to allow commoners in Parliament.

Fig. 506 – King Edward I in Parliament (16th century)

In 1341, under King Edward III (1312–1377), the commoners began to meet separately, forming the House of Commons, as opposed to the House of Lords for the nobility and the clergy. Members of the House of Commons were elected by male property owners. During his reign, Edward also agreed that no law could be passed, nor any tax levied, without the consent of both houses.

Henry VIII

Parliament gained even more power under Henry VIII (1491–1547). Henry desperately wanted a male heir, but his wife Catherine of Aragon (1485–1536) gave birth to just one daughter, named Mary I (1516–1558). Frustrated by this, Henry began to believe that this was God’s way of telling him that his marriage was illegitimate, since Catherine was his brother’s widowed wife. As a result, he began to question his marriage. In the meantime, Henry had fallen in love with Anne Boleyn (c. 1501–1536) (after first sleeping with her sister Mary). But Anne had no inclination to become just one of Henry’s mistresses, claiming she would only be with him as his wife. As a result, Henry asked the pope for permission to divorce, but this request was rejected. In response, the Protestant politician Thomas Cromwell (c. 1485–1540) proposed an unorthodox solution. He advised the king to reject Catholicism and make himself “the supreme head of the Church of England,” thereby giving himself the authority to annul his marriage. Given the boldness of this move, he called Parliament to legitimize his decision. When Parliament agreed, the churches of England, formerly under the authority of the pope, transitioned to the new Anglican faith. Henry also closed monasteries and sold them to enrich the treasury. To replace the Church’s role as distributor of charity, Cromwell started a social welfare program, called the Poor Law, to help the “deserving poor,” which included the sick, widows, and children (but not unemployed men).

Fig. 507 – Henry VIII, by Hans Holbein (c. 1537) (Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Spain)

Unfortunately for Henry, Anne couldn’t give him a son either. As a result, he accused her of adultery and had her beheaded. His third wife, Jane Seymour (c. 1508–1537), finally gave him a male successor named Edward VI (1537–1553). When Jane died soon after childbirth, Henry acquired a fourth, and shortly thereafter, a fifth wife. His fifth wife was the Catholic Catherine Howard (c. 1523–1542), who convinced Henry to back away from further Protestant reforms and even had him execute Thomas Cromwell. Eventually, Henry had her executed as well, after which he married his sixth and final wife.

Henry was succeeded by Edward VI, but he died young, after which Mary I was proclaimed queen. Mary was a Catholic and set out to undo the Reformation. In an attempt to achieve this, she famously burned 260 Protestants at the stake, for which she earned the nickname Bloody Mary. John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments of the English People described her victims as Protestant martyrs, causing a lasting distrust of Catholics in England.

The English Civil War

In 1629, King Charles I (1600–1649) was in need of financial aid, but Parliament refused to grant it until the king addressed various grievances about illegal taxation and various religious reforms. In response, Charles dissolved Parliament and ruled without it for eleven years. But when supporters of Parliament won a landslide electoral victory, Charles reluctantly agreed to sign the Triennial Act, which ended illegal taxation and required the king to call Parliament into session at least once every three years. That same year, Charles also needed money to suppress a rebellion of Irish Catholics. Parliament agreed to fund the campaign, but did not trust the king to command the army. Instead, it passed the Militia Bill, which allowed Parliament to select generals to head military campaigns. This stripped the king of his most fundamental responsibility, namely defending his country. Charles could not accept this and responded by ordering the arrest of various members of Parliament. His attempt failed, and in return, Parliament initiated the English Civil War (1642–1651).

In 1645, Parliament authorized the formation of the New Model Army, led by a number of Protestant Puritans. The Puritans, also referred to as Dissenters or Non-conformists, were religious dissenters who held Calvinist beliefs and sought to purify the Anglican Church. They emphasized the importance of a personal relationship with God and rejected elaborate rituals and the necessity of a priestly class in favor of a simpler morally upright life. Among them was the cavalry commander Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658). With Cromwell’s help, Parliament won the civil war and captured the king. A majority in Parliament still believed in the king’s divine right to rule, but Cromwell was convinced there would be no peace in England as long as the king was alive. To get rid of him, the army expelled most moderate members of Parliament, leaving behind what came to be known as the Rump Parliament. This Parliament set out to charge the king with treason. Since treason was defined as a crime against the king, Charles demanded to know by what authority the court sat. Parliament answered:

In the name and on behalf of the people of England.

In 1649, King Charles was found guilty and was executed.

Without a king, England became a republic, known as the Commonwealth. The new government abolished the Church of England, ended press censorship, and allowed for the widespread printing of the Bible. In 1653, a delegation of the army named Cromwell Lord Protector, giving him powers that were ironically very similar to those of former kings. In fact, he was more powerful than his predecessors because he had access to a standing army.

Fig. 508 – Oliver Cromwell, by Samuel Cooper (based on a work from 1656) (National Portrait Gallery, Britain)

The Glorious Revolution

Not long after Cromwell’s death, a new Parliament was elected that wanted the monarchy restored. They made Charles I’s son, Charles II (1630–1685), their new king. Understandably, many supporters of the king saw the Puritans as dangerous radicals for their role in the execution of Charles I. As a result, they were heavily suppressed.

Charles was succeeded by his brother James II (1633–1701), who was an open Catholic. Charles had ensured that James’s daughters were raised Protestant, ensuring he would have a Protestant successor. But then, in 1687, James had a son with his second wife, who he planned to raise as his Catholic heir. In response, a group of seven noblemen, known as the Immortal Seven, gathered in secret to invite Stadholder William III of Orange (1650–1702)—the political leader of the Dutch Republic and husband of James’s daughter Mary II (1662–1694)—to invade England. In 1689, William and Mary were offered the crown by Parliament. Once in power, William adopted the Bill of Rights. The Bill condemned James II for abusing power and declared that a monarch could not rule without the consent of Parliament—turning England into a constitutional monarchy. It also stated that no king of England could tax or own a standing army without parliamentary permission. Additionally, the bill promised the freedom to elect members of Parliament without the king’s interference and “freedom of speech and debates or proceedings in Parliament.” William also agreed to a parliamentary commission to examine his expenditure and he agreed to the Act of Settlement, which ensured Britain could only be ruled by Protestant rulers. Dissenters were granted the Act of Toleration, which allowed them to worship openly. Catholics, for the time being, were still considered suspect, but in time, toleration was granted to them as well (especially when the Counter-Reformation subsided).

The ousting of James II and the subsequent adoption of the Bill of Rights became known as the Glorious Revolution, which—miraculously—had occurred without any bloodshed.

The Social Contract

Greek and Roman philosophers had thought deeply about what constitutes just government. They believed in what they called natural laws, which, as defined by Aristotle and Cicero, were laws not particular to any city, country, or ruler, but true throughout the entire universe on the basis of reason. Almost all of the great philosophers of the 17th and 18th centuries expanded on this idea by creating their own theory on legitimate government.

An early example came from Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), in his work called Leviathan, which became one of the founding texts of modern political philosophy. Hobbes postulated that before society existed—when mankind lived in the state of nature—all men competed violently with each other for scarce resources. It was a time of “war; and such a war, as is of every man, against every man.” Since there were no laws at that point, there was no such thing as good or evil. Everyone was just acting out their natural impulses. To escape this nightmare, rational and self-interested individuals entered into a social contract with their peers, agreeing to give up some of their freedom in return for safety. They had to “lay down [their] right to all things; and be contented with so much liberty against other men, as he would allow other men against himself.” But since a contract only has true value unless it can be enforced, this freedom had to be surrendered to a leader or a government. Hobbes preferred a monarch, believing that fearing one monarch was better than to fear everyone. This king, Hobbes claimed, should have full power over the state church and should demand religious unity to avoid warfare.

The British philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) presented the most influential social contract theory in his Two Treatises of Government, which he wrote in exile in the Netherlands. Locke didn’t share Hobbes’s draconian vision of the state of nature. In his view, people would live in peace most of the time in the absence of a state, but at times, some would “seek absolute power” over others. According to Locke, this is not acceptable, as it violates natural rights. In his view, these rights were created by God and were therefore universally valid and predated any type of government. Following Cicero, he believed these rights could be discovered through reason. He summarized his theory as follows:

Reason [...] teaches all mankind who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions. [343]

Any ruler who denies people these natural rights, he claimed, was illegitimate, giving the community the right to revolt. Given these convictions, it is no wonder Locke was a strong supporter of the Glorious Revolution. Locke had earlier opposed King James II’s claim to the divine right of kings and was even suspected of involvement in a failed plot to assassinate both him and his brother King Charles II. Locke also likely met King William III before his invasion and was invited by his wife Mary on her boat back to England.

So, what is the best form of government? According to Locke, a government should rule exclusively with the consent of the governed and should only exercise whatever power is given up by the social contract. As governments throughout history have misused their power, he recommended limiting this power as much as possible.

Locke, in his Letter Concerning Toleration, also famously argued in favor of religious toleration, which he claimed was in line with Christianity, for “rather than to lord it over others, true Christians leave others alone and focus on correcting themselves.” He reasoned that while many rulers feared that toleration of different religions would inevitably lead to war, Locke claimed it was instead the oppression of the “diversity of opinion, […] that has produced all the bustles and wars that have been in the Christian world upon account of religion.”

Even Locke’s toleration, however, did not extend to Catholics, as they were loyal to a foreign power (the papacy). Similarly, he remained suspicious of atheists, as he believed atheism would destroy society (as the “taking away of God […] dissolves all.”)

Cato’s Letters

Between 1720 and 1723, John Trenchard (c. 1691–1750) and Thomas Gordon (1662–1723) wrote an influential series of essays known as Cato’s Letters, named after the Roman politician Cato the Younger (95–46 BC), who defended the Roman Republic against Caesar. In these letters, Trenchard and Gordon promoted freedom and warned against the despotic tendencies of governments.

Letter No. 15, written by Gordon, famously defended free speech as an antidote to tyranny, stating:

Freedom of speech is the great bulwark of liberty; they prosper and die together: And it is the terror of traitors and oppressors, and a barrier against them. [136]

Letters No. 32, 100, and 101 addressed libel and slander, tackling the difficult question of how far free speech should extend, as even proponents often see dangers in a completely “unbounded liberty of the press.” For instance, what about spreading damaging rumors about a public figure? Gordon erred on the side of freedom, believing the downsides of press freedom were “an evil arising out of a much greater good”:

I must own, that I would rather many libels should escape, than the liberty of the press should be infringed.

He concluded that “private and personal failings” of politicians should be off bounds, but not when they “enter into their public administration.” Especially exposing crimes that affect the public can “never be a libel” and should instead be “a duty which every man owes to truth and his country.” Although slander can harm generally good men, Gordon claimed it is better to allow this, since it is worse than not being able to accuse wicked men.

The English East India Company

Britain acquired its first colony already in 1541, when King Henry VIII proclaimed himself King of Ireland and set the goal of civilizing its “barbarous people.” Half a century later, Britain started looking further away for its colonies, but was met with fierce competition from Spain and Portugal. In these early days, the British sea captains hoped to colonize areas rich in gold, but they generally failed, after which they plundered their competitors instead (which was encouraged by the English government). One of these men was Henry Morgan (c. 1635–1688), who in 1663 raided a Spanish outpost in the Caribbean to steal gold. After England acquired Jamaica in 1655, Morgan did take the next step and settled on the island, which was ideal for growing sugar cane. Its production became so profitable that in the 1670s, the British Crown spent an enormous amount of money to build fortifications to protect the island’s main port from European competition. The construction was supervised by Henry Morgan himself, who became Acting Governor of Jamaica.

In 1600, a group of merchants and investors founded the English East India Company (EIC). The company initially had the goal of trading with India, Southeast Asia, and later China, but in time, the company also gained imperial ambitions, seizing control of large parts of India, parts of Southeast Asia, and Hong Kong. The company created various outposts on the Indian coast starting in 1608, among them Madras, Bombay and Calcutta, which the British turned into important trading hubs. With only a few outposts on the coast, the EIC had to operate with the permission of the Muslim Mughal Emperor to do business in India. The company paid the emperor bribes and sent representatives to his court who had to prostrate before him. From the 1740s, just when the Mughal Empire was losing ground, the EIC created its own army, staffed mostly by Indian warriors. In 1765, they were granted the right by the Mughal emperor to tax over 20 million Indians, making the company look more like a kingdom in its own right. Exploiting the internal feuds in India, supporting one side against another, the EIC slowly managed to take control over larger and larger parts of India. In 1815, there were 40 million Indians under British rule, and a century later 400 million, which were seldom governed by more than a thousand British civil servants.

Although the company’s main motive was financial gain, many Britons also developed a deep interest in Indian culture. They translated the Bhagavad Gita into English, founded an Islamic law school, and studied the geography and botany of the subcontinent. Some also adopted Indian customs and married Indian wives. Similarly, many Indians became interested in a British education, hoping to advance their career. But, of course, there was also exploitation. Within Britain itself, criticism mounted on the growing imperial ambitions of the EIC (more on this in the chapter on slavery). In 1785, the criticism centered around Governor-General Warren Hastings (1732–1818), who was impeached, put on trial, but was finally acquitted, for “extirpating the innocent and helpless people […] and depopulating the whole country.” It is entirely possible Hastings had done nothing that would have made people blink an eye even one generation earlier, but the morals of England had changed.

The British also colonized Australia, at a mind-boggling 26,000 kilometers from England, which they undertook not for trade, but because it could serve as a natural prison—a dumping ground for criminals. Between 1787 and 1853, Britain transported 123,000 men and 25,000 women to the island for various crimes, often for petty theft. Once in Australia, they were forced to work, but after a few years, they could regain their freedom. As the colony was quickly getting prosperous, only one in fourteen prisoners wished to return to England after their sentence. Some British criminals even favored going to Australia over a lighter sentence in England.

Criminals who reoffended in Australia were sent to Tasmania and two other nearby islands, where they received severe punishments. To make way, the natives of Tasmania were hunted down and exterminated, in what truly merits the term genocide. Again, there was a counterresponse in the British Parliament, where concern about the mistreatment of natives led to the appointment of Aboriginal Protectors in 1838, although with limited success.

The British also colonized the east coast of America, Canada, and a large part of Africa, as will be discussed in later chapters.

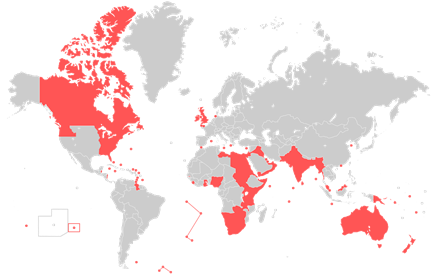

The British Empire

At its height, around 1920, the British Empire covered a record 25% of the world’s surface and population (see Fig. 509), becoming “The Empire on which the sun never sets” (a phrase earlier used to describe the Spanish global empire).

At the height of the empire, products from all over the world became part of British daily life. Sugar turned from a delicacy for the rich to a staple of daily life. The same happened for tobacco. According to Everybody’s Business is Nobody’s Business (1725) by Daniel Defoe, even “every plow-man had his pipe.” Textile and tea, too, became common goods. “Plain country Joan is now turned into a fine London madam, can drink tea, take snuff, and carry herself as high as the best.” Especially Indian fabrics “crept into our houses, our closets, our bedchambers; curtains, cushions, chairs, and at last beds themselves were nothing but Calicoes or Indian stuffs.” [344]

Fig. 509 – Map of all territories ever held by the British Empire (Geordie Bosanko, CC BY-SA 3.0)

James Cook

During the Age of Enlightenment, British scientists attempted to solve a problem that had plagued explorers from the start. While the position of the sun and the stars could be used to determine latitude (the position from north to south), there was not yet an accurate way to determine longitude (the position from east to west). As a result, ships regularly sailed off course, which had caused several naval disasters. It was already known this problem could be solved with a more accurate clock that would allow sailors to compare their local time to the time back home. This required far more stable timekeeping devices as they would have to withstand both the movement of the ships and variable weather conditions. In 1714, the British Parliament offered a prize of 20,000 pounds to whoever solved this problem. The brilliant British clockmaker John Harrison (1693–1776) worked for decades on the problem and finally succeeded. As a point of reference, the British arbitrarily set the Royal Greenwich Observatory as the prime meridian of zero degrees longitude.

The Age of Enlightenment also saw several voyages set out for the purpose of scientific exploration. The archetypal figure of this endeavor was James Cook (1728–1779), who became an explorer of heroic stature and achieved international fame. He was also known for his far greater tolerance towards natives. Cook sailed all across the world to make far more accurate maps. He also took with him a team of scientists, who studied the geography, flora, and fauna of the places they visited. In his 1768 journey, Cook set out specifically to observe and record a transit of Venus, which could be used to determine the distance of the sun. On this journey, he also was given a secret task to search for a fabled landmass in the Pacific Ocean that was supposed to balance out the landmasses on the Northern hemisphere. When he did not find it, he correctly concluded that it did not exist.

Cook also famously circumnavigated the globe without losing a single man to scurvy, which he achieved by feeding his men concentrated vegetable soup and pickled cabbage. He was also the first to enter the Antarctic Circle, where he discovered a landmass under the ice. Looking for the Northwest Passage, he stumbled on Hawaii. Continuing to the Bering Strait and encountering a wall of ice, he also concluded that the Northwest Passage did not exist.

Returning to Hawaii, Cook was struck on the head with a club and then stabbed to death by one of the natives. Because the natives held Cook in high esteem, they prepared his body with funerary rituals usually reserved for their chiefs. His body was disemboweled and then baked to remove his flesh. His bones were then carefully cleaned for preservation as a religious icon.

Fig. 510 – James Cook, by Nathaniel Dance-Holland (c. 1775) (National Maritime Museum, Britain)