Throughout most of history and across the world, the overwhelming majority of people had to deal with suffering, poverty, submission, and violence on a regular basis. In most cases, the few governed the many, demanding unquestionable obedience by force. Slavery was common across the world and women and minorities were often oppressed and considered lesser beings.

Despite the West being the home of reason, its history is also tainted with some of the most terrifying atrocities the world has ever seen, including the violent subjugation of colonies, the large-scale Transatlantic slave trade, and the Holocaust.

Paradoxically, it was the same West that made the greatest strides toward freedom and equality. In Britain, various Christian abolitionists—among them Quakers—helped convince the public to end the Transatlantic slave trade. Afterward, the British Navy was deployed in an attempt to end slavery across the world. They patrolled the coast of West Africa to intercept slave ships and then released the slaves in Freetown, Sierra Leone. In America, the abolition of slavery took longer, requiring a civil war. Abraham Lincoln won the war and amended the Constitution to make slavery illegal.

The slave trade

It is hard to grasp from a modern standpoint, but throughout most of history and throughout most of the world slavery was seen as a legitimate institution. Even the Roman Stoics and the early Christians, who advocated for a more humane treatment of slaves, did not oppose the institution itself.

One of the most egregious and well-documented examples of slavery was the transatlantic slave trade, starting in the 16th century and peaking in the second half of the 18th century. Making use of the direction of the winds, European ships would make a triangular journey across the Atlantic, known as the triangular trade. They would first sail downward along the African coast, where they picked up slaves, then they would sail westward to America, where they sold these slaves and picked up goods such as sugar, tobacco, and cotton, and then they sailed diagonally back to Europe, where they sold their goods. It is estimated that between 11 to 12 million slaves were shipped from Africa to America in this manner.

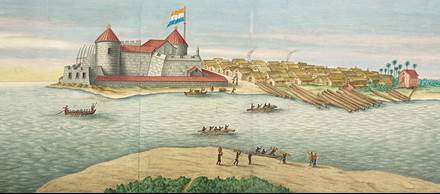

To acquire these slaves, it wasn’t necessary for Europeans to enter the African mainland, as an African slavery system was already in place. Rival African tribes kidnapped and enslaved one another and brought their slaves to dozens of slave forts along the west coast of Africa. These forts were owned by various European nations—including Sweden, Denmark, France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Portugal (see Fig. 535).

In the same period, another estimated 10-20 million African slaves were deported to Muslim lands as part of the Arab slave trade. The Arabs would castrate many of the males before their journey to prevent procreation. The procedure was very risky and many African men did not survive it. And then there was the Barbary slave trade, perpetrated by the Sultanate of Morocco and the Ottoman states in North Africa, who captured possibly up to a million European slaves, which were in high demand in their slave markets.

Unfortunately, these are only the most egregious examples of a global problem. Around 1800, over 75% of the global population was stuck in either slavery or serfdom. To give a sense of the numbers we’re talking about, the 1861 abolition of serfdom in Russia freed an estimated 23 million people.

Fig. 535 – Fort Elmina, built by the Portuguese in 1482 and taken over by the Dutch in 1637 in the Atlas Blaeu-Van der Hem (1660s)

The abolition of slavery in France

The abolition movement in France had a long history. The earliest evidence comes all the way from 1203, when two serf brothers in Toulouse (then not part of France) were granted freedom:

Such is the custom in the city of Toulouse that anyone from Toulouse cannot buy any person living in Toulouse nor acquire [such a person] in any way from anyone outside of Toulouse. [352]

Over the centuries many instances have been recorded of serfs and slaves being freed immediately upon arrival in the city. The idea slowly spread throughout France. In 1315, King Louis X (1289–1316) passed a decree that freed serfs from the Royal Domain (the part of France surrounding Paris). The decree stated that “according to the law of nature, everyone must be born free [franc]” but that many people “have ended up in bonds of servitude […], which greatly displeases us.” The decree continues:

We, considering that our Kingdom is called and named the Kingdom of the Francs, and wishing that the thing be in truth in accordance with its name, have ordained and do ordain, that throughout our kingdom […] such servitudes will be restored to freedom. [352]

In the second half of the 16th century, the idea that any slave reaching French soil should immediately be freed became widely accepted. In 1571, the Parliament in Bordeaux brought this into practice by releasing a shipment of slaves by a Norman merchant on the grounds that “France, mother of liberty, does not permit any slaves.” Five years later, the political theorist Jean Bodin (c. 1530 – 1596) saw the free-soil principle as a fundamental law of the French nation, stating that every slave “is free as soon as he sets foot in France.” [352]

Slavery was reinstated, however, in the French colonies. To oppose this, several supporters of the French Revolution formed the Society of the Friends of Blacks in 1788. Although the organization only had a few hundred members, they included important figures, such as Lafayette and Condorcet. Even the “villain” Robespierre opposed slavery. He claimed he was disgusted that the French National Assembly gave “constitutional sanction to slavery in the colonies.” Instead, he aimed for equality for people of all colors, as not to “compromise the interests humanity holds most dear, the sacred rights of a significant number of our fellow citizens.” [353]

In 1791, with the French Revolution in full force, the National Assembly granted full citizenship rights to all free men of color. The white colonists on the island of Saint-Dominique, however, ignored the new law. In response, an estimated 20,000 slaves rose up against their masters in what became one of the largest slave revolts in history. In 1794, as the fighting persisted, the National Assembly back in France made the historic move to abolish slavery in all French territories—although this would last for only eight years.

In 1801, the black rebel leader Toussaint L’Ouverture (1743–1803) managed to become the de facto ruler of Saint-Dominique (see Fig. 536). Although the island was still technically in French hands, he published his own constitution, which affirmed that slavery is illegal, allowed all men “whatever their color” to apply for any position, and made himself governor for life. When Napoleon came to power, he sent over his army and had Toussaint shipped to France, where he died in prison one year later. Napoleon also reopened the slave trade, but could not hold on to Saint-Dominique, which became independent in 1803 under the name Haiti.

Fig. 536 – Toussaint L’Ouverture (1802) (John Carter Brown Library, United States)

Fig. 537 – Logo of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (1795)

The abolition of slavery in Britain

Britain too developed a strong abolition movement and one with more long-term success. Here, the movement was mainly fueled by a Christian denomination known as the Religious Society of Friends, better known as the Quakers. Already in 1688, German-American Quakers from Germantown, Pennsylvania, had written and signed a document protesting slavery, calling on the Biblical wisdom to “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” In 1727, the British Quakers officially expressed their disapproval of the slave trade, and, in 1783, over 300 Quakers signed a petition for its abolition and presented it to Parliament. In 1787, nine Quakers joined forces with three Anglicans, forming the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. The famous entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795) mass-produced the logo of the organization on pottery medallions, which became extremely popular (see Fig. 537). One of the founders of the movement, the Anglican Thomas Clarkson (1760–1846), conducted research to expose the horrors of the slave trade. Based on his investigations, he drew a cross-section of a fully-loaded slave ship (see Fig. 538), hoping to further change the opinion of the British population in favor of the abolition movement.

The evangelical Christian William Wilberforce (1759–1833), another prominent member of the abolitionist movement, spoke out against slavery before Parliament with great determination:

I confess to you sir, so enormous so dreadful, so irremediable did its wickedness appear that my own mind was completely made up for the abolition. A trade founded in iniquity, and carried on as this was, must be abolished, let the policy be what it might—let the consequences be what they would, I from this time determined that I would never rest till I had effected its abolition. [354]

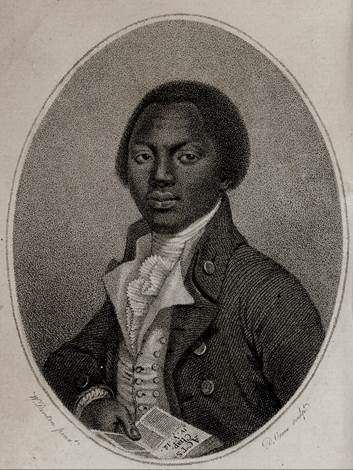

There were also a few black ex-slaves who spoke out. One of them was Olaudah Equiano (1745–1797). According to his influential autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Equiano was enslaved in Nigeria as a child by local kidnappers, who sold him to Westerners on the coast of Africa, where he was shipped to America. He described the horrible conditions on board the ship as follows:

![]() The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to

the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to

turn himself, almost suffocating us. This produced copious perspirations, so

that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome

smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died [...].

This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains.

[...] The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole

a scene of horror almost inconceivable. [355]

The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to

the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to

turn himself, almost suffocating us. This produced copious perspirations, so

that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome

smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died [...].

This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains.

[...] The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole

a scene of horror almost inconceivable. [355]

Some slaves even preferred death over slavery and jumped into the sea to drown themselves. When one of them was rescued against his will, he was flogged as punishment to deter others from doing the same.

Eventually, Equiano came into the hands of a relatively mild slave owner named Robert King, who fed him well, allowed him to go to school, and let him save money to purchase his own freedom, which he eventually did.[22]

Fig. 539 – Olaudah Equiano, by Daniel Orme (1789)

All these efforts combined achieved a collective change of heart in the British population. In the 1780s, huge numbers of people signed petitions to demand an end to the slave trade. The support became even strong enough to sway legislators. The first true milestone, however, had to wait until 1807, when Parliament passed the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. In the same year, the United States Congress also abolished the slave trade under the leadership of Thomas Jefferson.

The year after, the overpowered British Royal Navy was deployed to patrol the west coast of Africa, in order to capture slave ships sailing under any flag. All intercepted ships were then brought to Sierra Leone, where the abolitionist John Clarkson (1764–1828) had founded a city known as Freetown. There, the slaves walked under the Freedom Arch, on which was written: “Freed from slavery by British valor and philanthropy.” The ex-slaves were then given a quarter acre of land, a cooking pot, and a spade. The patrol was very successful. By 1840, thirty British warships had intercepted a stunning 425 slave ships. In 1850, the navy also successfully sent ships to Brazil, pressuring its government to abolish the slave trade.

The British effort to end the slave trade astonished some of the African tribal leaders, among them King Gezo from modern-day Benin, who sold 9000 slaves per year. He remarked:

The slave trade has been the ruling principle of my people. It is the source of their glory and wealth. Their songs celebrate their victories and the mother lulls the child to sleep with notes of triumph over an enemy reduced to slavery. Can I, by signing […] a treaty, change the sentiments of a whole people? [344]

The criminalization of the slave trade, however, had not ended slavery itself. A small step in the right direction came in 1814 when leaders of European nations gathered at the Congress of Vienna to seek a long-term peace plan after the Napoleonic Wars. The countries concluded that slavery was “repugnant to the principles of humanity and universal morality,” and the members signed a document in which they pledged to work towards its abolition. Yet, in reality, it still took a while. The British were the first to abolish slavery in their entire empire between 1833 and 1838.

The White Man’s Burden

Starting in the late 18th century and peaking in the Victorian era (1820–1914), the same Christian abolitionists also sought to convert the world to Christianity, with the aim of offering “simpler” cultures redemption through Jesus Christ. Instead of just ruling over others, they felt the British Empire also had an obligation to better the world by bringing civilization, which to them included Christianity. The British poet Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936) called this endeavor “the white man’s burden.” Today, this sentiment is often seen as patronizing, or even racist, yet it was on the mind of many of the great progressives of his day.

The British missionary David Livingstone (1813–1873) went to South Africa for this purpose, but had little success convincing the natives about the importance of Christianity. Eventually, he gave up and instead became an explorer. He became the first to traverse the African continent from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. On this journey, he discovered slavery was still rampant in Central and East Africa, organized from the East African coast by Arab and Portuguese slave traders. Out of empathy for the plight of the slaves, he set out to convince the British Empire to colonize the region, thereby bringing civilization and the abolition of slavery to Central Africa (and eventually, he hoped, Christianity as well). To make his case, he sailed across the Zambezi River, hoping it would give easy access to the African inland, but the river turned out to be non-navigable. Although his plan had failed, he would spend the rest of his life trying to stamp out slavery in the area, hoping, as his gravestone reads, “to help heal this open sore of the world.” [344] Livingstone died a disappointed man, yet just over a month later, the sultan of Zanzibar signed a treaty with Britain to abolish the East African slave trade. A former slave market was turned into a cathedral, with the altar symbolically at the location where slaves were once flogged.

In British India, missionary work was met with great resistance. Initially, the British East India Company (EIC) had no interest in Christianizing India, because it did not wish to disturb trade relations. They even prohibited missionary work. This changed in 1813 under pressure from British abolitionists, who claimed Hinduism was “a cruel religion [that had] to be removed.” [344] Their criticism was mostly aimed at the suttee ritual in which widows were burned alive on their husband’s funeral pyre. Thousands of these cases were reported. But many Indians had no interest in changing their religion. The Indian soldiers of the EIC even initiated a full-blown violent revolt against anyone associated with the British government, killing men, women, and children. The uprising came to be known as the Indian Mutiny. Britain responded equally harshly, but they did learn their lesson and gave up their attempt to Christianize India.

Early abolitionists in America

The abolition of slavery in America would take longer. In the 19th century, the United States was roughly divided into the North, centered around New England, which took full advantage of the Industrial Revolution, and the South, which was more agrarian and mainly focused on the production of cotton. The land in the south was often worked by slaves who were owned by a relatively small number of wealthy planters.

Politics split along the same lines. The Democratic Party dominated in the South and supported state’s rights, minimal government regulation, and slavery. The Republican Party, which was founded only in 1854, was less averse to federal intervention and was in support of the abolition of slavery. According to the Democrats, the abolition of slavery would destroy the economy. Moreover, they claimed, southern slaves had it better than the working class in New England. Most planters, was their reasoning, were friendly and provided their slaves with food and shelter, while in the North, workers were extorted as wage slaves in factories under terrible conditions. We find this myth in Aunt Phillis’s Cabin; or, Southern Life as It Is (1852) by Mary Henderson Eastman (1818–1887), who wrote this work as a reaction to the influential anti-slavery book Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which we will discuss shortly.

The slaves themselves came from diverse African tribes, speaking different languages, but over time, they managed to create a shared cultural identity as African Americans. Some met in secret “night meetings,” where they drank stolen alcohol, danced, and sang songs to get some relief from their tough life. Some of these songs were religious spirituals, the predecessors of the blues. For their subject matter, they often turned to Christianity, especially to Moses, who had helped the Jews escape from slavery in Egypt, and to the salvation promised by Jesus Christ. Both of these narratives gave them hope for a better future. The lyrics of one of these songs, named Go Down, Moses, reads:

Go down, Moses, way down in Egypt’s land;

Tell old Pharaoh to let my people go!

We need not always weep and moan. Let my people go.

And wear these slavery chains forlorn. Let my people go. [345]

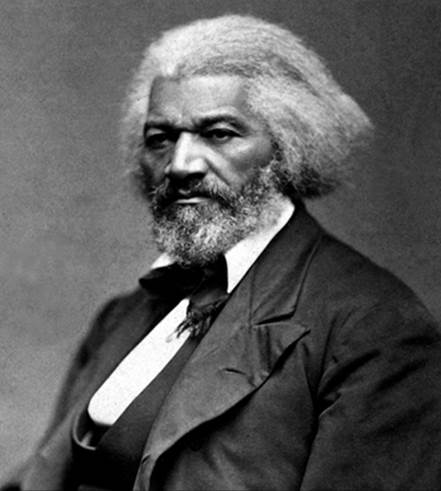

An escaped ex-slave named Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), who came to play a leading role in the abolition movement of America, claimed that “like tears, [these songs] were a relief to aching hearts.”

Tired of their plight, an estimated 10,000 slaves fled the South in search of freedom in the North. A network of secret routes and safe houses called the Underground Railroad, staffed by idealistic Christians, freed slaves, and also Native Americans, helped them on their way. Among them was Harriet Tubman (c. 1822–1913), herself an ex-slave, who helped some 300 fugitives make the journey.

Books helped spread awareness about the plight of slaves. For instance, Solomon Northup (c. 1808–1864), a freeborn African-American who was kidnapped into slavery and eventually regained his freedom, wrote Twelve Years a Slave (1853) in which he described the horrible conditions he experienced as a slave. Speakers also made a difference, the most important being Frederick Douglass, who powerfully claimed that slavery was unconstitutional, un-Christian, and contrary to natural law. In one of his brilliant speeches, he addressed his audience as follows:

I appear before the immense assembly this evening as a thief and a robber. I stole this head, these limbs, this body from my master, and ran off with them. [345]

Douglass told his audience he could not understand that all his former owners had been practicing Christians. One of his masters even claimed to have had a profound spiritual awakening, yet even this didn’t change how he treated his slaves. In fact, he became even “more cruel and hateful,” whipping a woman while reading a verse from the Bible: “The servant that knows his master’s will, and does it not, shall be beaten with many stripes.” [345]

Douglass also made a great defense for free speech, stating that it allowed the oppressed to speak. He was convinced “slavery cannot tolerate free speech,” as it is “the dread of tyrants.” “Five years of its exercise would banish the auction block and break every chain in the South.” [136] Douglass also wrote an autobiography called Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself (1845) and founded a newspaper called the North Star, the star used by runaway slaves to guide themselves to freedom.

In 1833, the Christian American William Lloyd Garrison (1805–1879) founded the American Anti-Slavery Society and also an anti-slavery newspaper called the Liberator. In the first edition he unapologetically wrote:

I will not retreat a single inch—and I WILL BE HEARD.

As a religious man, he considered slavery sinful. On top of this, it was in contradiction with the Declaration of Independence, which promised equality for everyone. He wrote:

Every Fourth of July, our Declaration of Independence is produced, with a sublime indignation, [...] but what a pitiful detail of grievances does this document present, in comparison with the wrongs which our slaves endure! [...] I am ashamed of my country. I am sick of our unmeaning declamation in praise of liberty and equality; of our hypocritical cant about the unalienable rights of man. [356]

Fig. 540 – Frederick Douglass (c. 1879) (National Archives, United States)

Fig. 541 – William Lloyd Garrison (1870) (Library of Congress, Unites States)

Garrison, like many other early abolitionists, encountered much resistance. At one point, he was dragged through the streets by a mob of white men. At another point, the South Carolina and Georgia legislatures promised a reward to anyone who kidnapped him and brought him to the South for trial.

Being a strict pacifist, Garrison was not willing to resort to violence, but instead aimed to shame the South into ending slavery. Elijah P. Lovejoy (1802–1837), a white editor of another anti-slavery newspaper, did not agree. He claimed to have received a sign from God to dedicate his life to the destruction of slavery. After a mob destroyed his printing office several times, Lovejoy and his supporters took up arms. He was killed when confronting the mob.

John Brown

Meanwhile, America was still expanding westward (at the expense of the Native Americans who often fiercely resisted). Back in 1775, thousands of settlers had followed pathfinder Daniel Boone into the rough terrain of Kentucky (named after the Cherokee word “Kentake,” meaning “great meadow”). Boone became one of America’s first folk heroes—the pioneers. Each time new terrain was won, farmers moved in, hoping to become wealthy on their new land. As the law was not set up yet in these frontier areas, life was generally very rough. It is estimated one in five pioneers died in their first few months. Eventually the pioneers reached California, where gold nuggets were discovered in 1848. The discovery attracted nearly 100,000 settlers from around the world, all infatuated by gold mania. In the years that followed, America produced about half of the world’s gold output and San Francisco grew in two years from 800 to 20,000 people.

The politicians of both the North and the South were anxious about the formation of new states, not knowing whether their senators would vote for or against slavery in Congress. This problem intensified in Kansas, which was founded in 1861. Two illegal governments competed to rule over the new state, one for and one against slavery, which soon led to a local civil war.

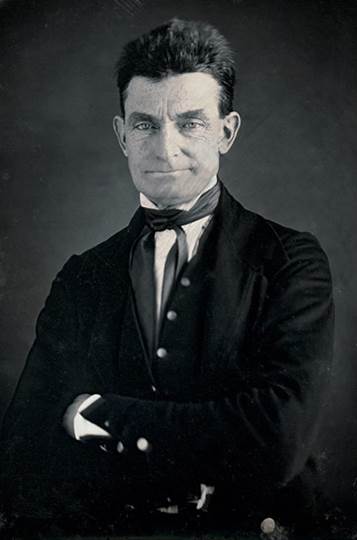

Fig. 542 – John Brown, by Augustus Washington (c. 1846)

And this is where John Brown (1800–1859) comes in. Brown had attended one of the many memorial services of Elijah P. Lovejoy, where he had raised his right hand and declared: “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!” Just as Lovejoy, Brown too was willing to die for his convictions. His goal was to organize an outright holy war against slavery, encouraging Christians to “break the jaws of the wicked.” John Brown and four of his twenty sons went to Kansas, dragged five pro-slavery men from their houses and hacked them to death with swords. Afterward, he showed no remorse, as the Bible stated: “without shedding blood, there is no remission of sins.” He added: “I want to free all the negroes in this state. If the citizens interfere with me, I must burn the town and have blood.” [345]

Then Brown made a plan to steal federal weapons, which he wanted to give to rebellious slaves in the hopes of triggering mass uprisings. Brown asked Douglass to join, but he declined, calling it a suicide mission that would “array the whole country against us.” [345] Brown replied that something startling had to be done to awaken the nation. Going through with the plan, Brown, with twenty of his followers, including three of his sons, entered an arsenal with 100,000 rifles. He soon got surrounded by armed townsmen. He managed to keep them out for 32 hours, but when they finally entered, one of the men plunged a sword into his chest. Brown survived and got convicted of treason, murder and “conspiring with Negroes to produce an insurrection.” Before he was hanged, he wrote a final message, stating that the “crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood.” [345] He then gave a speech expressing pride in his effort.

The reaction to his actions by fellow abolitionists was twofold. Garrison called him “misguided, wild and apparently insane,” while the great Romantic author and abolitionist Emerson (1803–1882) called him a “saint” who had made “the gallows glorious like a cross.” Douglass called him “our noblest American hero” and admitted his commitment to ending slavery “was far greater than mine.” [345]

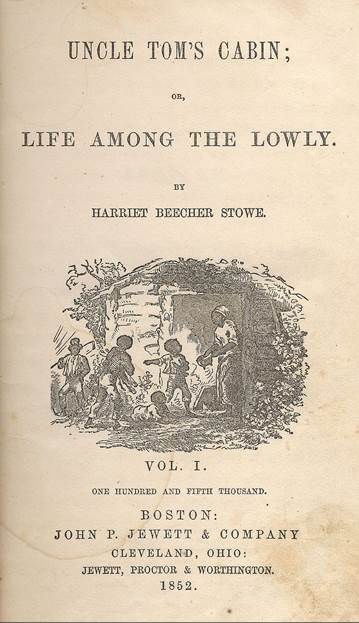

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

In 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896) wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or Life among the Lowly—perhaps the most influential novel ever published in the United States. The story tells of a dignified, almost saintly slave named Uncle Tom, who was being transported by boat to an auction in New Orleans. On his way, Tom saved the life of Little Eva, a kind young girl, whose grateful father then purchased him. Eva and Tom soon became great friends. But then Eva got fatally ill. On her deathbed, she asked her father to free his slaves. He agreed to do so, but was killed when intervening in a pub fight before he was able to fulfill his promise. A new owner called Simon took possession of Tom, while a few other slaves got away. When asked about the whereabouts of these slaves, Tom refused to answer, for which he was whipped to death while maintaining a Christian attitude throughout.

Fig. 543 – Harriet Beecher Stowe (National Archives, United States)

Fig. 544 – The cover of Uncle Tom’s cabin (1852) (Hammatt Billings)

In her book, Stowe called upon her readers to see slaves as fully human and deserving of our empathy as the Christian faith demanded. Take, for instance, the following discussion between a husband and his wife:

“There has been a law passed forbidding people to help off the slaves that come over from Kentucky, my dear.” “And what is the law? It don’t forbid us to shelter those poor creatures a night, does it, and to give ‘em something comfortable to eat, and a few old clothes, and send them quietly about their business?” “Why, yes, my dear; that would be aiding and abetting, you know.” “Now, John, I want to know if you think such a law as that is right and Christian?” “You won’t shoot me, now, Mary, if I say I do!” [...] “You ought to be ashamed, John! Poor, homeless, houseless creatures! It’s a shameful, wicked, abominable law, and I’ll break it, for one, the first time I get a chance; and I hope I shall have a chance, I do! Things have got to a pretty pass, if a woman can’t give a warm supper and a bed to poor, starving creatures, just because they are slaves, and have been abused and oppressed all their lives, poor things!” [...] “Now, John, I don’t know anything about politics, but I can read my Bible; and there I see that I must feed the hungry, clothe the naked, and comfort the desolate; and that Bible I mean to follow.” [357]

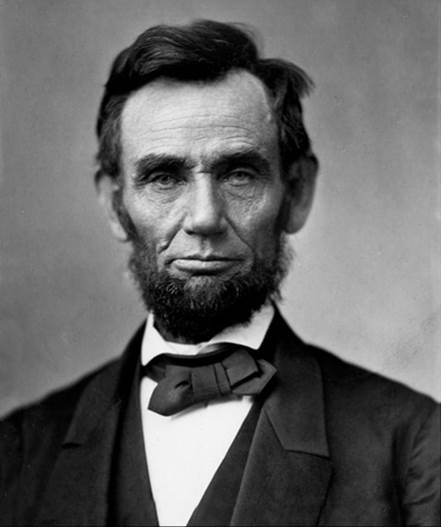

Fig. 545 – President Abraham Lincoln, by Alexander Gardner (1863) (Mead Art Museum, United States)

The influence of the book was so great that when Abraham Lincoln met Stow during the American Civil War, he supposedly greeted her with:

So, this is the little lady who started this great war. [358]

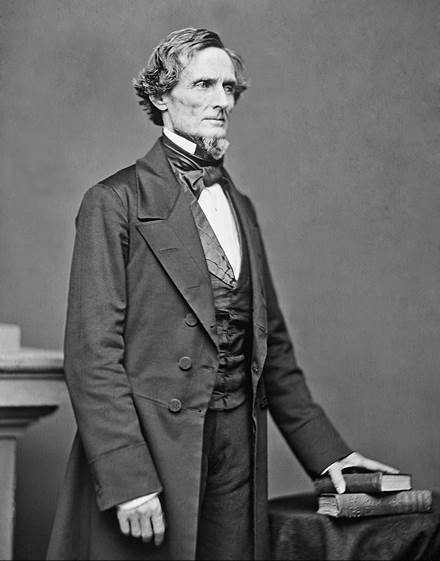

Fig. 546 – Jefferson Davis (1859) (National Archives, United States)

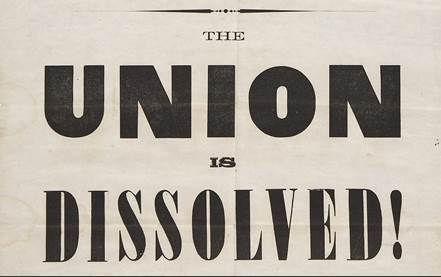

The Confederacy

With the majority of new states turning Republican, the pressure on the South was starting to mount. As a result, more and more Southerners wished to secede from the United States altogether. This was the situation when the Republican lawyer Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1861. Lincoln opposed slavery, calling it a “monstrous injustice,” but also knew being an uncompromising abolitionist would not get him elected. As a result, he promised the South he would not end slavery. To not upset a large part of the population, he also parroted plainly white supremacist ideas during his campaign. For instance, when his main political opponent accused him of secretly being an abolitionist, he countered:

I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races. […] I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermingling with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which will ever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together, there must be the position of superior. I am as much as any other man in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race. [345]

Before the inauguration, false rumors nevertheless spread that Lincoln planned to free all slaves. On top of this, Minnesota and Oregon entered the Union as free states, making the slave states a minority in the Senate. Feeling that their way of life was under threat, South Carolina appointed a convention to decide whether or not to remain in the Union. The southern states unanimously voted to secede, forming the Confederate States of America, or the Confederacy for short (see Fig. 547). Richmond became its capital and Jefferson Davis (1808–1889) its president. Alexander Stephens (1812–1883), Davis’s vice president, described the aims of the Confederacy as follows: “Our new government is founded upon […] the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.” [345]

The Confederacy then seized all federal property in their states, including arsenals and forts. One of these forts was manned by the Unionist Major Robert Anderson (1805–1871), who, together with 69 of his soldiers, did not give up his fort. The Confederates surrounded the fort and even opened fire. When their ammunition and food supplies were running low, Anderson finally lowered his flag and surrendered. Although Anderson and his men were allowed to evacuate, the event signaled to the North that war was now inevitable. The American Civil War had begun.

Fig. 547 – The cover of the Charleston Mercury, bringing news of the secession of the southern states (1860)

The American Civil War

To not further fan the flames, Lincoln emphasized at the start of the war that their fight was not about slavery. If the southern states were to return to the Union, he claimed, they could keep their slaves:

The paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all slaves, I would do it. [345]

But in 1862, Lincoln changed his mind. He signed an act to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia and then in the western territories. Later that same year, Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which warned the Confederacy that if they did not stop the fighting in 100 days, all their slaves were to be made “forever free.” He deemed this necessary to win the war, as the 3.5 million Confederate slaves were forced to contribute to the southern army. It became, in his words, “military necessity, absolutely necessary to the preservation of the Union. We must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued.” Planters in the South tried desperately to prevent their slaves from learning about the proclamation, but word spread around quickly, inspiring thousands of slaves to escape. Douglass called the proclamation a “righteous decree” and encouraged black men to join the Northern army, stating: “This is our chance, and woe betide us if we fail to embrace it.” [345] In total, more than 180,000 black men were enlisted, mostly men who had fled the south. When the 100 days had passed, on the first day of 1863, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, thereby freeing all slaves.

At Lincoln’s insistence, the House of Representatives also passed the 13th amendment to the Constitution, which banned slavery in all states. It became law in 1865, just after the war.

Fig. 548 – A black Union army sergeant (1864)

Fig. 549 – Dead men at Gettysburg, by Timothy O’Sullivan (1863)

The Union army, under the leadership of Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885), and the Confederate army, under the leadership of Robert E. Lee (1807–1870), clashed on many occasions. Their most significant encounter was the Battle of Gettysburg (1863), which was the largest battle ever fought in North America. Each side lost an estimated 20,000 men. On the location of the battle, the Republicans founded the Gettysburg National Cemetery. At its opening, Lincoln gave his famous Gettysburg Address, in which he claimed the conflict to be the ultimate test to see whether a nation “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal […] can long endure.” He concluded:

This nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth. [345]

After two more years of relentless fighting, the Union clearly got the upper hand. Lee recognized he had lost and met up with Grant, who assured him he would not be tried for treason if he signed the surrender documents. Jefferson Davis was imprisoned, but after just two years he too was released.

3.5 million slaves were now free, but they still had no homes, no jobs, no food, and no education. Many volunteers stepped in to help them get on their feet. Congress also established the Freedmen’s Bureau to provide medical care, food, clothing, and education.

In his second inaugural address, Lincoln aimed for unity. He stressed that vengeance had to be avoided at all costs and that reconciliation must be actively sought “with malice toward none, with charity for all,” in order to heal the country. In the audience was a young actor named John Wilkes Booth (1838–1865), who still supported the objectives of the Confederacy and claimed something “heroic” had to be done. Lincoln later gave a speech on the White House lawn in which he expressed his hope that literate freed blacks and those who had served the Union military would receive the vote. Again, Booth was in the audience. He wrote in his diary that Lincoln’s comments “meant n*gger citizenship.” “Now, by God,” he continued, “I’ll put him through. That is the last speech he will ever make.” [345] And so it happened. Lincoln went to see a play at Ford’s Theater in Washington D.C. where Booth slipped into the presidential box and shot the president in the head.

A year after Lincoln’s death, the 14th amendment was added to the Constitution, which granted citizenship to former slaves and ensured equal protection under the law for all citizens. In 1868, the 15th amendment gave voting rights to African American men.

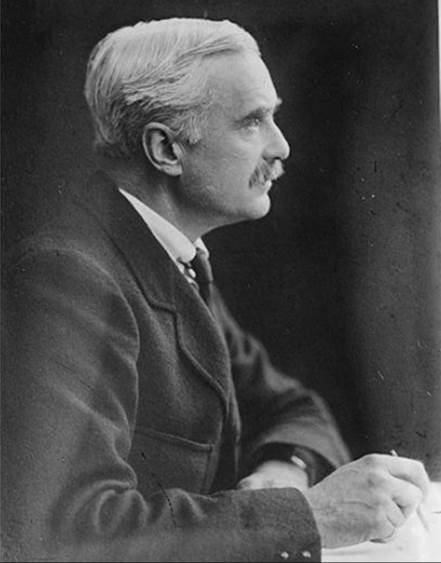

Fig. 550 – E. D. Morel (c. 1922) (Library of Congress, United States)

Belgian Congo

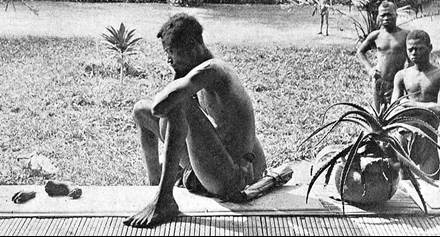

The British journalist E. D. Morel (1873–1924) was one of the most important activists to raise awareness of the violence committed against the indigenous peoples in Congo. Congo, at the time, was a Belgian colony under the direct rule of the Belgian king Leopold II (1835–1909). In the 1890s, Morel was working as a shipping clerk in Antwerp when he noticed discrepancies between the imports and exports to the Congo. Belgium exported firearms and ammunition and received a disproportionate amount of rubber, ivory, and other expensive goods in return. From this observation, Morel concluded that no commercial transactions were taking place but that the population of Congo was instead put to work by force. Deeply disturbed by this finding, he founded the Congo Reform Association and used his talents as a speaker and writer to spread awareness. He also distributed photographs sent over by a number of missionaries. One of these missionaries was Alice Harris (1870–1970), who took photographs of the horrific violence committed by the Belgian colonists, which included the cutting off of hands (see Fig. 551).

Fig. 551 – A photograph taken by Alice Harris and published in Morel’s King Leopold’s Rule in Africa. It shows Nsala looking at the severed hand and foot of his daughter (1904)

Both the company Morel worked for and various government officials tried to bribe him to stay quiet, but he refused, quit his job, and began to work full time for his cause:

[I started to work] with the determination to do my best to expose and destroy what I then knew to be legalized infamy. I knew that there lay concealed beneath the mask of a spurious philanthropy, and framed in all the misleading paraphernalia of civilized government, a perfected system of oppression, accompanied by unimaginable barbarities and responsible for a vast destruction of human life. [359]

In 1908, King Leopold II finally gave up his absolute rule of Congo and turned it over to the Belgian government, ending the most severe human rights abuses.