Unfortunately, the end of slavery did not mean the end of institutional racial segregation in America. In response, many great voices came out to protest, among them Martin Luther King Jr., who in 1963 gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. One year after, the Civil Rights Act was passed, outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

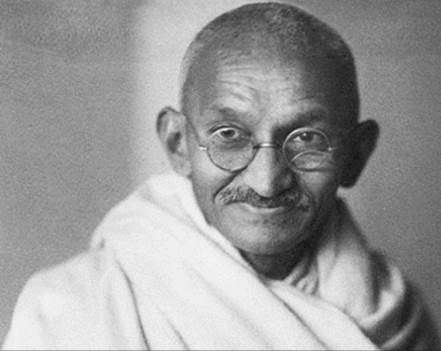

Britain still had its colonies after both World Wars, despite pressure from activist groups who demanded self-determination. In India, Gandhi had campaigned for decades to oust the British, using his satyagraha method of non-violent protest. The British responded brutally, which, especially in contrast to the noble Gandhi, discredited the Empire in the eyes of the world and even in the eyes of the British population. Shortly after the Second World War, bogged down by massive war debts, the British finally agreed to give up some (and eventually all) of their colonies, thereby ending their empire.

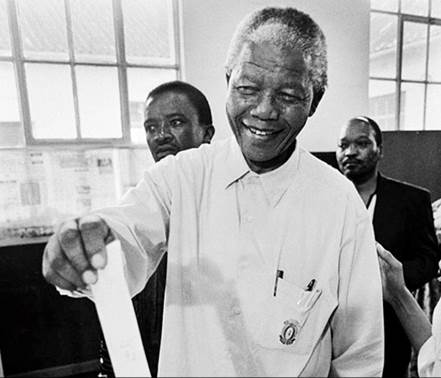

South Africa had to wait longer still for their system of segregation, known as apartheid, to end. Crucial here was the activism of Nelson Mandela, who with the help of international pressure, helped end the system in 1990. Not long after, he became president, promising a rainbow nation where black and white people can live together.

Fig. 552 – Segregation in America (1961)

America’s betrayal

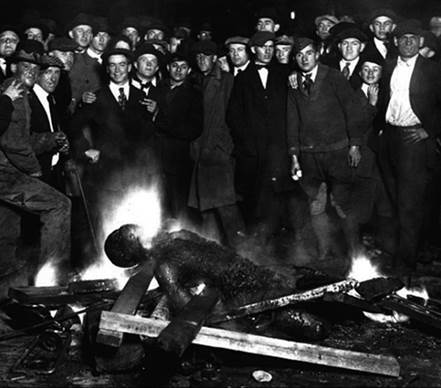

Unfortunately, the end of slavery did not mean the end of institutional racial segregation in America. The horrifying practice of lynching also continued, where informal mobs brutally killed black people suspected of a crime. For instance, Fig. 553 shows a mob of white men posing in front of the mutilated and burned body of Will Brown (d. 1919), who had been accused of raping a 19-year-old white woman. In some cases, the “crimes” committed were merely being disrespectful or being a part of the civil rights movement.

Fig. 553 – The lynching of Will Brown (1919)

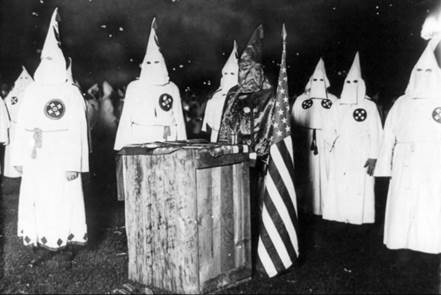

The Ku Klux Klan, which was founded by former Confederate officers after the Civil War, also continued to use violence and intimidation against the black community.

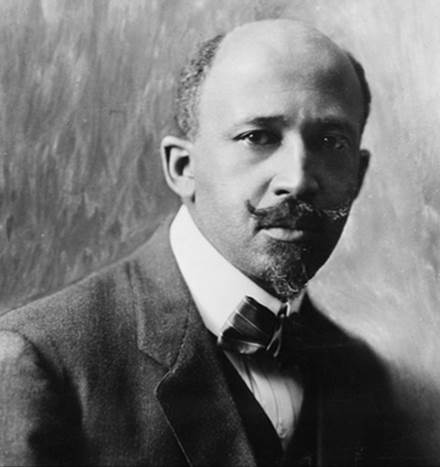

In 1909, the African-American activist W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which sought to fight for basic human rights for everyone, regardless of skin color. In his own words:

We will not be satisfied to take one jot or tittle less than our full manhood rights. We claim for ourselves every single right that belongs to a freeborn American, political, civil and social; and until we get these rights we will never cease to protest and assail the ears of America. The battle we wage is not for ourselves alone but for all true Americans. It is a fight for ideals, lest this, our common fatherland, false to its founding, become in truth “the land of the thief and the home of the slave”—a by-word and a hissing among the nations for its sounding pretensions and pitiful accomplishment. Never before in the modern age has a great and civilized folk threatened to adopt so cowardly a creed in the treatment of its fellow-citizens born and bred on its soil. Stripped of verbiage and subterfuge, and in its naked nastiness, the new American creed says: Fear to let black men even try to rise lest they become the equals of the white. And this is the land that professes to follow Jesus Christ. The blasphemy of such a course is only matched by its cowardice. [360]

Fig. 554 – The Ku Klux Klan (c. 1920) (Library of Congress, United States)

Fig. 555 – W. E. B. Du Bois (1918) (Library of Congress, United States)

Du Bois saw hope on the horizon when President Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924) led America into the First World War. Wilson claimed that the goal of American involvement in the war was to “make the world safe for democracy,” and he promised equality to the racial minorities who fought on his side. As a result, Du Bois urged his fellow African Americans to join the army to earn their rights as American citizens. Many followed his call. Gandhi did the same, encouraging Indians to volunteer to fight for the British Empire, which many did with full commitment.

In 1919, a year after the war, the victorious countries organized the Paris Peace Conference. The goal of the conference was to set the peace terms, but also to ensure that a similar war would not happen in the future. During the conference, the League of Nations was formed, the first international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. But not every part of the conference was successful. Eleven out of the 28 countries that joined the conference refused to accept that all races were created equal. One of these countries was the United States. The U.S. also refused to join the League for fear that it might challenge their practice of racial segregation.

Du Bois also showed up at the Paris Peace Conference, where he helped to organize the Pan-African Congress, aimed at drawing attention to racial discrimination. When he discovered that the United States was not willing to keep its promises, he reacted with astonishment and anger. He felt betrayed, but he was not willing to back down:

We stand again to look America squarely in the face and call a spade a spade. [...] We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting. Make way for Democracy! We saved it from France, and by the Great Jehovah, we will save it in the United States of America, or know the reason why. [361]

The fall of the British Empire

The right to self-determination for the British colonies was also denied at the Paris Peace Conference, sparking riots in various countries. Yet there were many signs that the British Empire was starting to crack, mainly because it was starting to lose its superior financial position in the world, in large part because of the war. Its war debt was so great that just paying the interest on the debt consumed close to half of the national budget by the mid-1920s. The empire also became more difficult to defend. Low on cash, they had decreased military spending, just at a time when the modern weaponry of their opponents made it more and more difficult to defend their huge empire. In the meantime, England also experienced a mental shift—they slowly but surely lost faith in the idea of empire altogether. More and more, it was seen as absurd that one people would rule over another. With Britain weak, various oppositional movements in the colonies took their chances. Britain often responded brutally (as we will see later in this chapter) but would thereafter experience a backlash from its own population in the form of protests. In many cases, Britain then made concessions to appease its citizens. Yet Britain would need a second World War to finally give up their empire.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

In order to promote peace, the League of Nations was assigned to define universal rights to have an objective standard by which to hold countries accountable for their actions. In 1924, the members adopted the Declaration of the Rights of the Child, which was the first declaration on human rights ever adopted by an intergovernmental institution. During the Geneva Convention of 1929, a treaty was signed to protect the rights of prisoners of war, including the right to be free from torture. The League also established the Health Organization and the Refugee Organization.

But then things went downhill. In 1933, Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) came to power in Germany. He openly expressed hatred for the League of Nations and called the rights of man “an invention by weaklings and fools.” When a petition was sent to the League of Nations about his dangerous behavior, Hitler immediately withdrew from the organization. The League of Nations was finally dissolved in 1939 as it had failed to prevent the Second World War.

After the war, in 1945, a peace conference was held in San Francisco, during which the United Nations (UN) was formed. During the conference, the Holocaust became public knowledge. This convinced many countries that some atrocities committed by governments were so horrific, that it required international intervention. This was felt even stronger during the Nuremberg trials, in which war criminals from Nazi Germany were prosecuted. To the shock of the world, some Nazi criminals tried to justify their actions by claiming Germany was a sovereign state, meaning that it was their own business how they treated their people.

During the war, in 1941, the American president Franklin Roosevelt (1882–1946) and the British prime minister Winston Churchill (1874–1965) had signed the Atlantic Charter, which spoke of world peace and human rights. The charter also stated that people should have the right to choose their own government.

But after the war, America was—for the second time—unwilling to keep its promise of ending racial segregation. Britain also remained unwilling to let its colonies go, as this would end their empire. When the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union met to discuss the design of the United Nations, they even tried to stay quiet on the subject altogether, but this provoked enormous protests across the world. As a result, they finally gave in and agreed that the protection of human rights should become one of the central goals of the organization. This objective was set down in writing in the United Nations Charter:

We the peoples of the United Nations determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind, and to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small. [362]

In the years after the war, Britain finally agreed to give up India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and later Malaysia; America gave up the Philippines; France gave up Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam; and the Netherlands gave up Indonesia. In 1960, called the Year of Africa, another 17 nations gained their independence.

Fig. 556 – Eleanor Roosevelt (1933) (Library of Congress, United States)

America, however, remained unwilling to end racial segregation. The UN could do nothing about it, since the United Nations Charter had one major flaw. While Article 1 of the charter explicitly called for equal rights and self-determination, Article 2 allowed countries to hide behind claims of national sovereignty as it stated that “nothing contained in the present Charter shall authorize the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state.”

Nevertheless, the document did set an international standard by which to judge governments, and it wouldn’t take long before various governments were challenged before the UN. For instance, South Africa was challenged by India for the treatment of its Indian population under its system of racial discrimination called apartheid. The United States was challenged by W. E. B. Du Bois over its policies of racial segregation, discrimination, and lynching. In most cases, however, the accused governments referred to Article 2, claiming their policies were their own business.

Although the charter had spoken generally about human rights, it had not yet defined them. This problem was solved when the United Nations established the Commission on Human Rights. The head of the commission was Eleanor Roosevelt (1884–1962), the former first lady, who had a long history of standing up for human rights, including being on the board of the NAACP. She established the Committee on the Philosophic Principles of the Rights of Man, which was made up of experts on the great religious and philosophical traditions of the world. Together they identified which rights to include in the bill. The result was The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was approved by the United Nations in 1948. The document is regarded as one of the most important in world history. The first two articles read:

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.

- Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.

The rest of the articles sum up many of the rights we have already encountered in this book, such as the right to be free of slavery and torture, the right to free speech and equality under the law, the right to hold public office, and the right to equal pay for equal work. The declaration wasn’t binding, but over the years, a number of its articles have turned into international law.

In 2002, another milestone was reached when the International Criminal Court (ICC) was established in The Hague, in the Netherlands. The organization was given the responsibility of investigating and prosecuting leaders charged with war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide.

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Gandhi (1869–1948), also known by his spiritual title Mahatma Gandhi, was born in India, studied law in England, and moved to South Africa at the age of 23. There he experienced the racism of South Africa first-hand. On the train, he was beaten for sitting with the whites instead of on the floor and he was kicked to the streets by a police officer simply for using a public footpath. These experiences led him to found the Natal Indian Congress in 1894 to turn the Indian community of South Africa into a unified political force. Working as a lawyer, he also defended Indian citizens subjected to racial discrimination. As expected, his actions were met with a lot of resistance. At one point, he was even attacked by a mob trying to lynch him.

At this point in his life, Gandhi did buy into the idea that blacks were inferior to whites, but he later changed his mind and became a strong advocate against racism of any kind.

In 1906, Gandhi adopted his famous satyagraha method of non-violent protest, with “satyagraha” meaning “holding on to truth.” He often combined this with calls for civil disobedience and non-cooperation. For instance, he urged his fellow Indians to defy a law that compelled them to carry a certificate of identity and to accept the resulting punishment.

In 1909, in his book Hind Swaraj (“Indian Home Rule”), he argued that British rule over India only persisted because the Indians cooperated. Without their cooperation, he claimed, British rule would collapse, and Indians could finally rule their own country again. He finally returned to India in 1915, at the age of 45, making Indian independence his major goal.

In 1919, Gandhi protested the Rowlatt Act, which allowed for detention without trial. He cautioned the viceroy of India that if the British passed the act, he would command the Indians to start satyagraha. When the British government ignored him, he announced a protest in Delhi. In response, British officials warned him not to enter the city. When he defied the order, he was arrested. At the protest, his followers were surrounded by British officers, who opened fire, murdering hundreds of people. Instead of criticizing the British, Gandhi criticized the Indians who had fought back. Gandhi asked his followers not to use violence, even when the British did. Instead, he claimed, they should express their frustration with peace. He even undertook a fast-unto-death, which he would maintain unless the Indians stopped their rioting. He did advise Indians to boycott British goods and institutions, to resign from government employment, and to forsake British titles and honors.

In 1921, Gandhi worked his way up to become the leader of an organization called the Indian National Congress. Around the same time, he also began to wear the Indian loincloth to identify himself with India’s rural poor. During this time, he lived modestly, ate simple vegetarian food, and undertook long fasts as a means of both self-purification and social protest. He also led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, expanding women’s rights, increasing religious and ethnic tolerance, and, above all, leading India to independence. Living by example, it was said he “made humility and truth more powerful than empires.” Despite his peaceful methods, he was jailed for two years in 1922. At the trial, he gave a famous speech in which he protested laws limiting freedom of speech, which were “designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen.” Freedom of speech, he claimed, were “the two lungs that are absolutely necessary for a man to breathe the oxygen of liberty.” [136]

In 1930, Gandhi organized another satyagraha, the Salt March, to protest a tax on salt. He and 78 volunteers marched almost 400 kilometers to a small village named Dandi, where he evaporated seawater to make salt for free, in defiance of the salt laws. This act of non-violent civil disobedience sparked millions of Indians to do the same. Along his march, he often spoke to huge crowds, and he was joined by thousands of Indians when he reached Dandi.

After Dandi, Gandhi continued to the Dharasana Salt Works, but before reaching it, he was arrested. The march continued without him, but then British forces showed up, attacking the crowd with clubs. Following Gandhi’s teachings, the marchers did not even raise their arms to fend off the blows. Two were killed, and hundreds were beaten. The American journalist Webb Miller wrote about the event:

At a word of command, scores of native policemen [under British command] rushed upon the advancing marchers and rained blows on their heads with their steel-shot lathis [long bamboo sticks]. Not one of the marchers even raised an arm to fend off blows. They went down like ninepins. From where I stood I heard the sickening whack of the clubs on unprotected skulls. [...] Those struck down fell sprawling, unconscious or writhing with fractured skulls or broken shoulders. [363]

Not surprisingly, this act of barbarism did much to damage Britain’s reputation. Gandhi criticized the West for their “brute force and immorality” and contrasted it with the “soul force and morality” of the Indians. To reassert their dominance, the British responded by imprisoning over 60,000 people.

Fig. 557 – Mohandas Gandhi (1931) (Elliot & Fry, PD)

Fig. 558 – Gandhi leading the Salt March (1930) (Wikimedia, PD)

In 1942, Gandhi demanded immediate independence, but the British responded by imprisoning him once more, together with tens of thousands of Indian National Congress members. Independence finally came in 1947 after a wave of international protests. Against Gandhi’s wishes, Britain first partitioned India into two dominions, a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan. As a result, many Hindus and Muslims had to migrate, leading to an overwhelming refugee crisis, which often turned violent. Gandhi visited the affected areas and undertook several fasts-unto-death to promote religious harmony. The last of these, when he was 78, also had the indirect goal of pressuring India to pay out some cash assets owed to Pakistan. Some Indians, however, thought Gandhi was too accommodating to the Pakistanis. Among them was a Hindu nationalist who assassinated Gandhi in 1948 by firing three bullets into his chest.

The civil rights movement

Despite international pressure, America held on to its system of racial segregation. When non-white delegates of the United Nations came to America for a conference, they experienced racial discrimination first-hand. They were refused service in restaurants, hotels, and public transportation. The Soviet Union also cleverly used segregation to shame the United States before the eyes of all the world. With each passing year, it became less believable for America to claim they were the beacon of freedom in the world with so many injustices going on at home. In 1947, President Harry Truman (1884–1972) published a report entitled To Secure These Rights, in which America finally took an honest look in the mirror:

Throughout the Pacific, Latin America, Africa, the Near, Middle, and Far East, the treatment which our Negroes receive is taken as a reflection of our attitudes toward all dark-skinned peoples. [This has] played into the hands of Communist propagandists. [...] The United States is not so strong, the final triumph of the democratic ideal is not so inevitable that we can ignore what the world thinks of us or our record. [...] To strengthen the right to equality of opportunity, the President’s Committee recommends: The elimination of segregation, based on race, color, creed, or national origin, from American life. [364]

Based on the report, Truman issued an executive order desegregating the armed forces and prohibiting all federal officials from discrimination on the basis of race or national origin. In 1948, the Supreme Court also put an end to land ownership restrictions based on race and it outlawed racially segregated schools in 1954.

In 1955, a woman by the name of Rosa Parks (1913–2005), as an act of protest, refused to give up her seat in the “colored section” of a bus when the “white section” had been filled, which got her arrested. She wasn’t the first to have done so, but somehow her timing was just right, as her act resulted in a bus boycott by the black community. Further protests followed across the country, and although they were often met with armed police, the activists persisted.

In 1963, a march with thousands of members met at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. Here Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968) gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech—one of the greatest and most influential speeches of all time. In his speech, he claimed that everybody, regardless of color, is endowed with the inalienable rights promised by the Declaration of Independence. We read:

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.” [365]

Following Gandhi, King discouraged resorting to violence and hatred to right these wrongs:

In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

We must forever continue our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force [a term coined by Gandhi].

The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people—for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is inextricably tied up with our destiny. They have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.

He then went on to list his complaints:

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights: “When will you be satisfied?” We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We can not be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating “For Whites Only.” We cannot be satisfied so long as the Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and the Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied and will not be satisfied until “justice rolls down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.” [Amos 5:24]

But then, instead of leaving his listeners in anger and despair, he presented a vision of hope:

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair. I say to you today, my friends, that in spite of the difficulties and frustrations of the moment, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed—we hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal. I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave-owners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a desert state, sweltering with the heat of injustice and oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today! I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification; one day right there in Alabama little black boys and little black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today! I have a dream that one day “every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.” [Isaiah 40:4]

This is our hope. This is the faith that I will go back to the South with. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day, this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with a new meaning: “My country, ‘tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim’s pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring [a patriotic song by Samuel Smith from 1831].” And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania! Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous peaks of California. But not only that. Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and every molehill of Mississippi, from every mountainside, let freedom ring! And when this happens, when we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!” [365]

Shortly after his speech, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. A year later, this was supplemented by the Voting Rights Act, prohibiting racial discrimination in voting. But then, in 1968, King was assassinated. His death was followed by riots all over the United States.

Fig. 559 – Martin Luther King during his “I have a dream”-speech (1963)

Mandela

The racial segregation in South Africa, known as apartheid, was still ongoing, but the black activist Nelson Mandela (1918–2013) became determined to put an end to it. In 1943, he joined the African National Congress (ANC), which was founded in 1912 to fight for equal rights for the black population of South Africa. At first, his protests were non-violent, but in 1960, when the police killed around 70 protesters, Mandela became convinced that violence was necessary to end apartheid. As a result, he co-founded the militant organization uMkhonto we Sizwe (shortened as MK). The organization carried out bombings to put pressure on the government, targeting military installations, power plants, telephone lines, transport links, and other crucial infrastructure. While the organization sought to avoid casualties officially, they also admitted to several bombings on public places, such as shopping malls and bars, causing the deaths of many civilians. Because of his involvement with the MK, Mandela was arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment for conspiring to overthrow the state in 1962. In 1985, after 23 years of imprisonment, he was offered his release as long as he “unconditionally rejected violence as a political weapon.” Mandela rejected the offer. The following statement was read on his behalf by his daughter:

What freedom am I being offered while the organization of the people [ANC] remains banned? [...] What freedom am I being offered when my very South African citizenship is not respected? Only free men can negotiate. A prisoner cannot enter into contracts. [366]

In 1990, faced with growing international pressure and fear of a racial civil war, the South African president F. W. de Klerk (1936–2021) finally did the right thing. He released Mandela and, in negotiation with him, dismantled the apartheid system and introduced universal suffrage. In 1994, Mandela led the ANC to victory, becoming the first black president of South Africa. He made national reconciliation the primary goal of his presidency, reassuring the white population that they, too, were protected and represented in his Rainbow Nation (a term coined by Desmond Tutu [1931–2021]). In his inaugural speech, he said:

We have triumphed in the effort to implant hope in the breasts of the millions of our people. We enter into a covenant that we shall build the society in which all South Africans, both black and white, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in their hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity—a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world. [367]

Fig. 560 – Mandela casting his vote (1994) (Paul Weinberg, CC BY-SA 3.0)