On top of this, economists discovered how to run an effective economy. The economist Adam Smith showed how a free market combined with property rights maximizes economic welfare and raises prosperity for both the working class and the elite. These two forces—machines and free trade—propelled the world into an era of unprecedented wealth, leading to a worldwide decline of poverty of around 80% over the last century.

Machines

The Industrial Revolution started in Britain, where engineers began to invent machines that greatly improved the rate of production. This made goods much cheaper and, therefore, available to a much wider part of the population. These developments made Britain the richest country in the world.

Fig. 573 – Inside a British cotton factory (1830s)

The cotton industry serves as a great example. The production of cotton used to be expensive as it had to be woven by hand on slow, heavy looms that required two people to work. The cost dramatically dropped because of a whole array of inventions that made every step of production much easier:

- In 1733, the flying shuttle was invented. It had a lighter and quicker loom that required only one person to operate it. This doubled productivity.

- In 1763, the spinning jenny was invented. It often contained eight spindles, increasing production by a factor of eight.

- In 1769, the water frame was invented, which strengthened the thread by twisting it before it entered the spinning jenny. This prevented the thread from breaking, which used to cause delays in production.

- In 1793, the cotton gin was invented, which efficiently separated cotton fibers from their seeds.

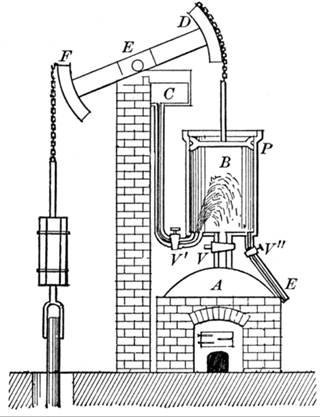

Fig. 574 – Newcomen’s steam engine, by Newton Black (1913)

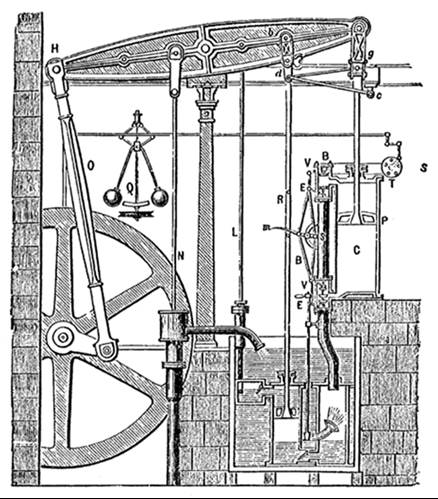

Fig. 575 – Watt’s steam engine, by Robert Thurston (1784)

After the 1760s, it also became common to power spinning jennies with waterwheels, which again dramatically increased productivity, but did require factories to be located near running water. The answer to this problem was steam. In 1712, Thomas Newcomen (1664–1729) invented an “atmospheric engine” that could pump water out of mines. The engine was powered by burning coal, which released enough energy to turn water into steam. The steam, in turn, pushed out a piston, making the pump operational. It was the first practical steam engine (see Fig. 574). In 1769, James Watt (1736–1819) greatly improved the steam engine, allowing it to work much faster and giving it a much wider range of applications. In Newcomen’s version, the steam had to be cooled with water sprays to get the piston back into its original position for reuse. James Watt modified the engine by allowing the steam to escape to a second condensing chamber, which was cooled by cold water. He also attached a revolving wheel to the piston to create circular motion, which allowed the machine to replace the waterwheel (see Fig. 575). By 1820, a spinning jenny powered by a steam engine could do the work of twenty spinners. As a consequence, factory owners made great profits, and consumers had access to cheap, high-quality clothes.

But the early engines also had their downsides. They were very dangerous to operate as the hot boilers could explode due to the enormous pressure. This problem was solved by the development of new furnaces that reached temperatures hot enough to melt steel. Compared to iron, steel is much stronger and more flexible, making it able to withstand much higher pressures.

In the 1820s, steam engines were also used to power trains and steamships, which made trade and communication both cheaper and faster. While it cost five weeks to cross the Atlantic by sail, the steam engine reduced this to about two weeks in the 1830s and just ten days in the 1880s. Trains connected British cities, and steamships allowed Britain to connect to the entire world, which increased Britain’s wealth even further. Britain’s new iron battleships also made the British Royal Navy the most powerful in the world by far.

Communication also greatly improved when Samuel Morse (1791–1872), in 1837, commercialized the telegraph system, which was first developed by Francis Ronalds (1788–1873) in 1816. It allowed messages to be sent through metal wires using electricity. In 1851, undersea cables were placed across the English Channel to connect England with mainland Europe. In 1866, a similar cable crossed the Atlantic Ocean, connecting Ireland to Canada. In the 1880s a total of 160,000 cables lay across the world’s oceans, linking Britain to India, Canada, Africa and Australia.

At first, telegraphs were sent through electric wiring, but they became wireless when Guglielmo Marconi, (1874–1937) managed to send stable signals across the Atlantic Ocean in 1894, using technology first discovered by Heinrich Hertz (1857–1894) in 1888.

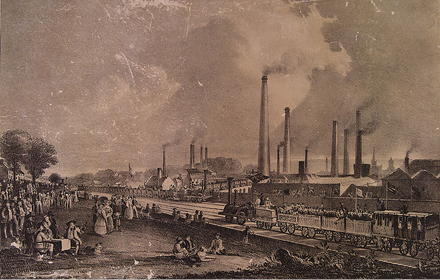

Fig. 576 – Britain during the Industrial Revolution, by D. Hill (1831)

The heroic engineers

The heroes of the Industrial Revolution were genius businessmen and engineers who received worldwide recognition by improving the world through their astonishing accomplishments. An early example was Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795), whom we have earlier discussed for his role in the abolition movement. Wedgwood was an apprentice potter who developed a disease that made him unable to operate the pedals on the pottery wheel. To circumvent the problem, he built a pottery factory in Manchester, which became a huge success. Wedgwood also invented direct mail, shipping his products all over Britain, and eventually across the world.

Fig. 577: Empire State Building (1931) (Sam Valadi, CC BY 2.0)

Fig. 578 – A Ford Model T (1910) (Harry Shipler)

Other significant accomplishments were the creation of the Suez Canal (1859), the Panama Canal (1881), and the American Transcontinental Railroad (1863). In 1884, the development of the steel frame allowed the building of the Home Insurance Building in Chicago, which is recognized as the world’s first skyscraper, counting 10 floors. Over time, the height of skyscrapers greatly increased. The most iconic ones were built in New York, among them the Chrysler Building (77 floors) and the Empire State Building (102 floors), which were both constructed in 1931.

In 1909, Henry Ford (1863–1947) began to mass-produce the automobile on assembly lines, making it affordable to the middle class. Ford had a clear vision for the world:

I’m going to democratize the automobile. When I’m through, everybody will be able to afford one, and just about everybody will have one. [383]

The machine gun

European imperialism intensified during the Industrial Revolution. In 1839, Britain easily defeated China in the Opium War, forcing them to open their markets to opium from India. British power only increased later in the 19th century, with the invention of the machine gun, which could be produced on a mass scale in British factories, making Britain as good as undefeatable until the rest of the world caught up. The first one, the Gatling gun, appeared in 1862. It had a mechanical loading mechanism, but still had to be powered by hand. In 1884, the Maxim gun solved this problem, using recoil energy to automatically reload the weapon.

Africa’s mainland was conquered in the last twenty years of the 19th century. Earlier, the West only had access to a few coastal outposts of Africa, but the interior was still largely uncharted. In 1893, the British imperialist Cecil Rhodes (1853–1902) sent an invasion force against the Ndebele (Matabele) Kingdom in modern-day Zimbabwe. Although the African kingdom had a strong army by African standards, they were no match for the Maxim guns, which could fire 500 rounds per minute, allowing them to literally clear a battlefield. We read that “the Matabele never got nearer than 100 yards [and] mowed them down literally like grass.” [344] It was the first use of the weapon in battle. 1500 African warriors were killed, with only 4 British casualties. A similar battle was fought in Sudan in 1898 between the British Empire and Sudanese Muslims. The battle took under five hours, during which about 10,000 Sudanese were killed with fewer than 100 casualties on British side. A young Winston Churchill, who witnessed the war as a correspondent for the Morning Post, was impressed by the courage of the Sudanese fighters, but they stood no chance against what he called “that mechanical scattering of death.”

Eventually, however, other parts of the world started to catch up with their own industrial revolutions, shrinking the power advantage of the West considerably.

The economy

The increase in prosperity was further enhanced by new developments in the field of economics. The start of the modern financial system can be traced to late-medieval Italy, where the merchant class came to dominate. Since rich merchants needed a secure place to store their gold, they contacted goldsmiths since they had the best vaults. As they earned interest for their service, some goldsmiths eventually became full-time bankers. In case both the buyer and the seller had an account with the same goldsmith, it was not necessary for the gold to actually leave the safe. Instead, the goldsmith issued receipts for the gold deposits, which could be used for payment. This introduced paper money to the European market (China had already developed it in the seventh century). Eventually goldsmiths discovered that the total amount of gold in the safes stayed roughly equal over time as the amount added was about equal to the amount withdrawn, which is known as the Goldsmiths’ principle. This allowed goldsmiths to invest a fraction of the gold. The medieval Italians also invented insurance contracts. Venetian merchants often shipped their goods across the Mediterranean. Since the financial risk of losing a ship was great, merchants started to pool money together to cover these costs collectively. Soon it became profitable for insurance companies to take up this role.

As mentioned in an earlier chapter, the Dutch established the first stock exchange in Amsterdam in 1602, which allowed companies to sell stocks to finance big expensive projects, such as the building of ships for trade. In 1624, the Dutch founded New Amsterdam on the North American coast, bringing their financial system with them.

When the British took over the city—renaming it New York—they added their groundbreaking legal system to the Dutch banking system. Britain had realized that it was important for the government to back business contracts by settling disputes with an impartial judge. This made both sellers and buyers less vulnerable to economic crimes, which in turn made them less reluctant to trade, which is great for the economy. The British government also backed property rights, which guaranteed merchants that their property wouldn’t be taken away on a whim. With the combination of Dutch and British influences, New York became the financial center of the world.

The free market

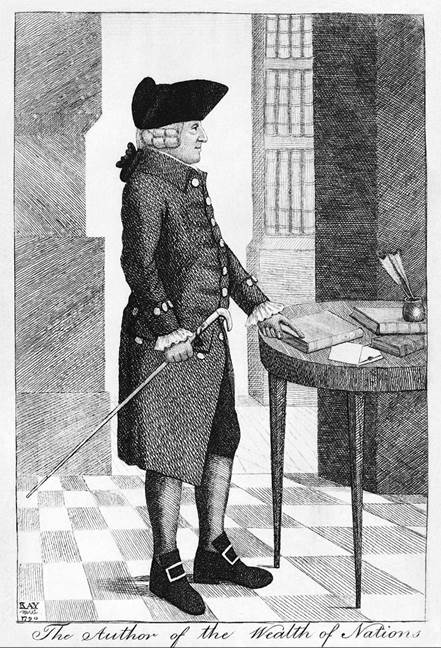

Adam Smith (1723–1790) is generally regarded as the first and most important economist in world history. In 1776, he published An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, or in short, The Wealth of Nations, in which he attempted to explain why some nations became wealthy while others failed.

In his book, he made the most famous observation in all of economics. Most governments exercised tight controls over their economies, but even when the leaders had good intentions, Smith showed, this was usually counterproductive. Counterintuitively, Smith found that when all individuals were allowed to trade according to their own self-interest in a free market, they often automatically maximized the well-being of society as a whole. He started with the observation that most processes of the market function properly when all members follow their own interest:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. [384]

Fig. 579 – Adam Smith by John Kay (1790) (Library of Congress)

In a free market, business owners are incentivized to make as much money as possible, but at the same time, customers generally opt for the cheapest products, pushing business owners to innovate to reduce their prices, which, in turn, increases the living standard of the population. This process also puts ineffective competitors out of business, as they will quickly lose customers. In conclusion, the system automatically puts the most competent people in charge of production. To Smith’s amazement, this all happened by itself without government interference in the market. Somehow the individual “selfish” actions of all the sellers and buyers combined conspire to guide the economy to its maximal result as though it was magically guided by an invisible hand. He wrote:

Every individual [...] neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. [...] He intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good. [384]

To further help the invisible hand do its job, Smith also encouraged people to not automatically take on the profession of their parents, which was the norm at the time. By allowing people to choose their own profession, they will generally pick something they are good at, which will both make them more money and increase the supply of the goods they are producing. This, in turn, lowers prices and thereby raises the standard of living of the entire population. Specialization can similarly make the market more effective. When people specialize in making one product, or even one part of one product, they are more likely to find better and faster ways to do their job.

The government can further help the invisible hand by closely monitoring the market to avoid people rigging the system and by providing public education, which allows people to qualify for the positions they are best at.

Over two centuries of experience has repeatedly confirmed Smith’s theory. The most extreme comparisons are the economies of North and South Korea or those of East and West Germany during the Cold War. In both cases, a genetically identical population with a shared history adopted either a communist or a free-market system. The communist systems became plagued by economic collapse, famine, and corruption, while the free-market systems prospered.

Smith’s theory can also explain the difference in wealth between North and South America. The British colonies in North America had become much more prosperous than their Spanish counterparts in South America. This was remarkable, especially since South America was much richer in resources, including silver and gold. Today, this difference can be elegantly explained. Firstly, the Spanish imported the medieval feudal system into South America, where powerful elites were given huge tracts of lands on which the lower classes were forced to work—the complete opposite of a free market. In contrast, Britain had its Common Law system, which applied equally to everyone, had impartial judges, diffusion of political power, some democratic elements, a measure of equal opportunity, and secured property rights. All these elements made life in the British colonies more predictable, which encouraged trade.

Secondly, Spain was an extractive empire, meaning the primary purpose of settlers was to quickly gain wealth and then return home. England, with much less access to easy wealth, instead was forced to create self-sustaining permanent settlements to survive, which was more beneficial in the long run.

Market failure

Smith also recognized there were exceptions, where leaving the market to fend for itself could lead to problems, known as market failure. For instance, when one company gains a monopoly on the sale of a good or service, it impedes the invisible hand. For example, if a town only has one water source, the owner of this well can increase prices and lower quality without repercussions since competitors are not available. To avoid this, the government has to ensure that there is a chance for competition in every sector.

Market failure can also be caused by negative externalities, which are negative consequences of a commercial transaction that fall neither on the seller nor the buyer, and, therefore, are not automatically factored in when determining the price. An important example is the pollution of the environment or child labor. An economic exchange can be beneficial for both buyer and seller, but the additional pollution it produces can decrease the economic welfare of the population as a whole. Government intervention can correct these problems.

Smith also recognized that free markets create a wealth gap, which he considered a necessary evil of a market society. Let’s illustrate this with an example. Imagine farmland being distributed equally among farmers in a poor community. As is common in human endeavors, a couple of farmers will greatly outperform the rest, producing more food and, therefore, making more money. Eventually their ineffective neighbors will voluntarily sell their land for a good price, knowing the land is not of great value to them but of much value to the effective farmers. Applying their superior skills on more land, these farmers become even richer, contributing to the wealth gap, but they also flood the market with an enormous amount of food at a low price, thereby ending hunger in the community. An alternative would be to close the market, forcing all owners to stay on their equal plot of land. In this system, the effective farmers can only use their skills on their small patch of land, while the majority of farmers turn their fields into wastelands. As a result, prices will rise dramatically, collapsing the economy and causing starvation in the community.

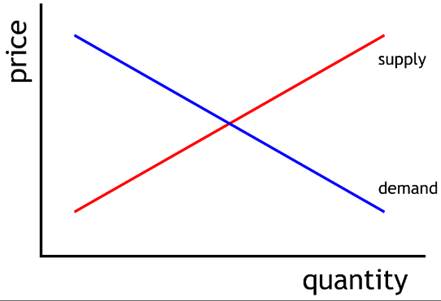

Fig. 580 – The law of supply and demand (S. P. Dinkgreve, worldhistorybook.com)

Supply and demand

Trying to follow in Newton’s footsteps, Smith also found two laws governing economic exchanges, known as the law of supply and the law of demand. The law of demand states that when the price of a product rises, the demand for this product drops as people become less incentivized to buy it. The law of supply states that when the price of a product rises, the supply of this product rises as people become more willing to sell it. While Adam Smith had described these concepts in words, Alfred Marshall (1842–1924) described them graphically (see Fig. 580). Marshall concluded that the actions of individual buyers and sellers generally push the market to the equilibrium at the intersection of these two curves, where the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded are equal. How does this happen? If a seller increases the price of a product above its equilibrium position, this raises the supply and lowers the demand, creating a surplus. The only way for the sellers to get rid of their products is to drop the prices back to the equilibrium position. Similarly, if the price drops below equilibrium, it raises the demand but lowers the supply, creating a shortage. This is problematic because it discourages business owners from producing valuable goods. The problem is solved by raising the prices back up.

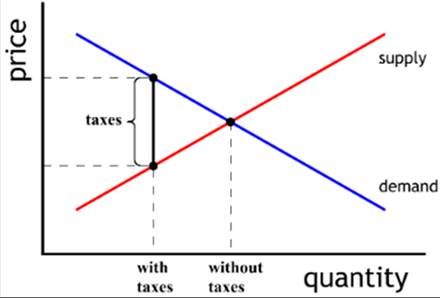

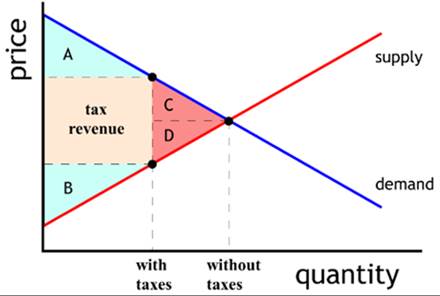

Interestingly, taxes force prices away from their equilibrium position as they increase the price for the consumer and lower the profits for the producer (see Fig. 581). But taxation does more than just take a cut from both the seller and the buyer. It also creates an economic barrier which prevents many exchanges from taking place in the first place. Since exchanges in a free market are voluntary, both parties will generally benefit (as otherwise they would not make the sale). But when taxation stops some exchanges from happening, it removes this benefit, thereby shrinking the economy of a country. The economic benefit lost by taxation is called the economic deadweight (see Fig. 582). Of course, taxation is useful in that it can finance public goods and services, but this analysis reminds us not to raise taxes carelessly.

Fig. 581 – A graph showing how taxation decreases the quantity of products sold by raising the price for the consumer and lowering the profits for the seller (S. P. Dinkgreve, worldhistorybook.com)

Fig. 582 – Area A represents the value gained by the consumers for making the sale and area B represents the value gained by the producer. The tax revenue is equal to the area insight the rectangle. Area C and D represent the economic deadweight lost because of taxation. (S. P. Dinkgreve, worldhistorybook.com)

Comparative advantage

The second great classical economist was David Ricardo (1772–1823). In 1817, he released his book Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, in which he showed that countries always benefit from trade, even if a country is less efficient at creating products. He called this the principle of comparative advantage.

Let’s start with a simple example. Assume Britain can produce clothes at a lower cost than Portugal and that Portugal can produce wine at a lower cost than Britain. This makes the production of wine relatively expensive for Britain and the production of clothes relatively cheap. It is, therefore, economically wise for Britain to specialize in making clothes, creating a surplus that they can trade with Portugal for wine. Similarly, it is wise for Portugal to specialize in making wine and to trade its surplus for clothing. As a result, both countries end up with more clothing and more wine compared to the situation in which they didn’t trade. It is a win-win situation for both countries.

Surprisingly, this reasoning even works if one country is worse at creating both products. Say it costs Britain 100 hours to make one batch of clothes and 200 hours to make one batch of wine, while it costs Portugal 20 hours to make the same amount of clothes and 10 hours to make wine:

|

|

Cloth |

Wine |

|

Britain |

100 h |

200 h |

|

Portugal |

20 h |

10 h |

Clearly, Portugal is better at producing both products. Still, trading can be shown to be beneficial for both parties. It would take Britain 100 + 200 = 300 hours to make one of each product, and it would take Portugal 20 + 10 = 30 hours to do the same. As a result, the countries would end up with a total of two batches of clothes and two batches of wine. But Britain could have also specialized in making 300/100 = 3 batches of clothes in the same period, while Portugal could have made 30/10 = 3 batches of wine. Now we have a total of three batches of clothes and three batches of wine! The two countries can then trade to obtain both products. The trick here is that, although it takes longer for Britain to make both products, it does have an easier time making clothes compared to wine (100 h instead of 200 h). This gives Britain a comparative advantage for making clothes, allowing it to profit from trade.

Ricardo famously put his theory into practice. During the Napoleonic Wars, the British government put tariffs on the import of grains from France to reduce the income of French farmers. When the war ended, British farmers understandably wanted the embargo to continue as it reduced their competition. Although Ricardo acknowledged that these laws were beneficial for the British farmers, they also made the rest of Britain dependent on their more expensive crops. The tariffs, therefore, basically functioned as a tax on the rest of the country, causing them to lose money that could otherwise be invested in new businesses, hiring new staff, investing in new equipment, and so on. On top of this, tariffs removed competitive incentives for the British farmers to innovate and lower their prices.

Britain eventually repealed the tariffs, but France did not. As a result, they maintained their small-scale and inefficient farms for most of the 19th century, causing France to stay poor, while Britain became the wealthiest country on the planet.

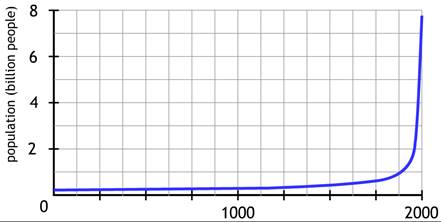

Fig. 583 – Growth in world population (S. P. Dinkgreve, worldhistorybook.com, after S. Pinker, Enlightenment Now)

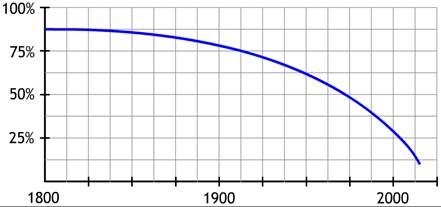

Fig. 584 – Decline in the percentage of people living under the absolute poverty line (S. P. Dinkgreve, worldhistorybook.com, after S. Pinker, Enlightenment Now)

The decline of poverty

The third great classical economist was Thomas Malthus (1766–1834). Malthus discovered that the food supply of the world was increasing linearly, while the population was increasing exponentially (see Fig. 583). Extrapolating this into the future, he reasoned that the population would soon run out of food. Luckily, his prediction did not come true, for Malthus had not foreseen the impact of the Industrial Revolution. He had underestimated the ability of free-market capitalism in combination with technological innovations—which would include artificial fertilizer and engines running on fossil fuel—to increase the food supply. These changes also strongly impacted average wages. For centuries, wages had been fluctuating without a clear sign of progress, but during the 19th century, they shot through the roof. As a result, poverty dramatically decreased worldwide despite the unprecedented rise in population (see Fig. 584). Around 1800, around 90% of the world’s population lived under the absolute poverty line. Today, it’s below 10%!

Keynesian economics

The great economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) sought ways to make capitalism more stable. Most Western governments today have a relatively free market economy for reasons mentioned earlier, but governments do manipulate the economy to influence overall economic performance. These interventions were first proposed by Keynes with the purpose of making recessions less severe. Keynes noticed that individuals and businesses tend to cut their spending at the start of an economic downturn to increase their savings to prepare for harsher years. Although this seems sensible, it leads to the following problem. If one person spends less, another person earns less, which will cause this person to spend less as well. This can create a cycle of economic depression that can spread throughout the entire economy, causing incomes to drop, production to fall, and unemployment to rise. Keynes called this phenomenon the paradox of thrift.

To avoid this problem, Keynes suggested a number of measures to help stabilize the economy in the event of an economic downturn. One stabilizing measure is unemployment insurance, which allows the unemployed to retain some of their spending power, allowing them to continue to support the businesses that depend on them. Another measure is a progressive income tax, which leaves more money to spend in case wages drop. Central banks are another stabilizing influence. They can lower interest rates to make it easier for individuals to get loans to invest in businesses or housing. Additional government spending can also help as it puts tax money back into the hands of workers. A tax cut also leaves people with more money to spend. A combination of these interventions was used as a stimulus package after the 2008 economic recession. Although this economic downturn was severe, these measures likely helped reduce the damage done by the recession.

Yet not all economists agree that these measures actually work. For instance, the economist Milton Friedman (1912–2006) believed activist governments create more problems than they solve. For instance, government intervention is likely to put a country into more debt. Since this debt needs to be repaid in the future, it will suppress the economy later down the road. Moreover, governments are much less efficient at spending money than free markets as their spending often impedes competition (a government might, for instance, finance one railroad company, creating a monopoly). About this, Friedman famously said:

If you put the federal government in charge of the Sahara Desert, in five years there’d be a shortage of sand. [385]

The success of liberal democracies

In the last couple of chapters, we have discussed the creation of a number of principles that have created unprecedented wealth and equality. These principles are combined in the most successful form of government discovered thus far, the liberal democracy. Essential ingredients are a representative democracy with free elections, a constitution, separation of power, a free market economy, private property, and the protection of human rights for all citizens. This brilliant combination of Enlightenment principles has resulted in higher rates of economic growth, fewer wars, healthier and better-educated citizens, and virtually no famines.